While most critters in the woods make their presence known only by signs left behind, there is at least one who is bold and loud and ever present in my neck of the woods. It often begins the day with a salute of drumming on a hollow snag to mark its territory just after the sun rises, and then I hear it or see it fly about our yard and woods and across the field beyond the stonewall throughout the day.

Every once in a while it honors me with a chance for a closer look. And so this afternoon, as I headed off into the woods to snip some twigs for an upcoming class that I’m teaching, I noticed some evidence that my friend had been present in the recent past.

It was the wood chips on the snow that served as his calling card. Well, his first card that is. By these, I knew he’d been chiseling the tree above, but always, when I spot this behavior I look for a second sign. And came up empty-handed. No scat.

While I was looking, however, I began to realize I could hear a familiar tap, tap, tapping from another tree.

And so I looked around, expecting to find one of his cousins, for the taps, though consistent, were not as loud as the drumming he uses to advertise his territory or announce his availability to a potential mate, but rather featured a softer rhythm.

Much to my delight, there he was, high up in a White Pine.

I was sure we wouldn’t get to spend too much time together, and so I wanted to focus on him as best I could. And that’s when I noticed the bark had been sloughed off the tree. My friend was hunting for bark beetles.

I decided to take my chances and move a few steps in order to get a clear picture, and still he stayed, though I thought our time might be over when he looked away from the tree.

Thankfully it wasn’t. Do you see all of the tunnels the beetles had carved where the bark had once been?

Oh, and how do I know it was a male? By the red mustache on his cheek. His lady does not have such a marking.

He turned back toward his work and I loved how it was obvious that his tail feathers formed the third leg of a tripod to provide support against the tree. When you have a head-banging job such as his, and only two legs, that third is important.

Eventually I pulled myself away and continued on my quest to locate certain tree species and snip just enough twig samples for each pair of students. Along the way, however, there were other things to notice like this recently deposited Bobcat scat offering a classic look at its hair-filled contents and sectioned presentation.

There are a million tracks in the woods right now since everything has been on the move following the last snowstorm, and the Foxes and Coyotes and Bobcats have been in dating mode, so it was no surprise to find Bobcat prints on top of other prints left behind.

Besides all the mammal tracks, I found lots of evidence of Ruffed Grouse walking about as well. They always remind me of my friend ArGee, whom I met in 2018, and wrote about several times, including this post Nothing to Grouse About. I may never get to have the experience of spending some quality time with a Grouse again, but seeing the tracks of one so clearly defined always makes me smile.

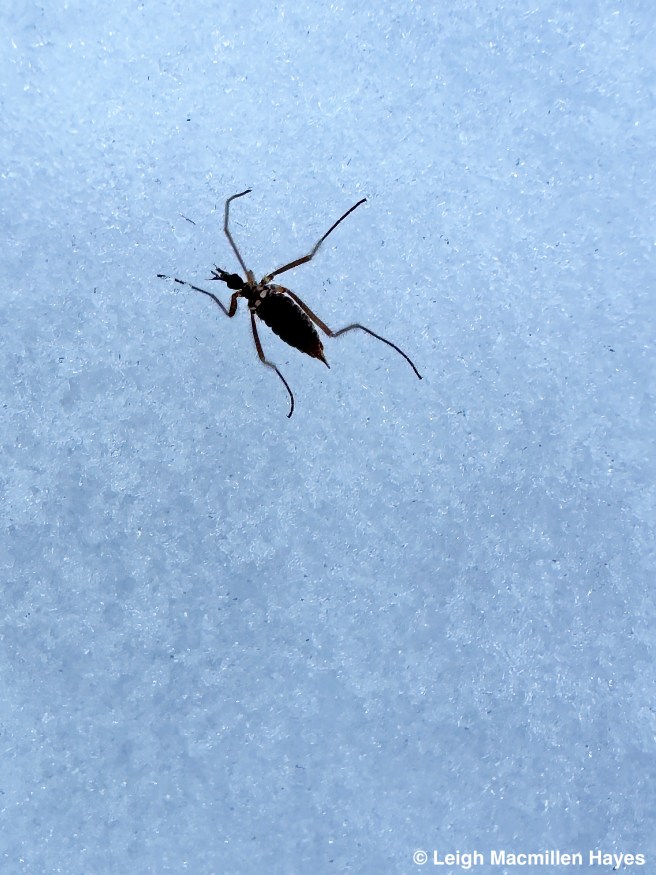

Another who has become a constant companion this winter is the Winter Crane Fly. Like all Crane Flies, he’s not a mosquito, though he looks like an oversized one. Crane Flies have no mouth parts, therefore, they can’t seek your blood. It’s only job is to find a mate and breed.

They are called Crane Flies because of their long legs and beaks that long ago were thought to resemble a Sandhill or Whooping Crane.

So why fly in winter? Perhaps because your predators are few. And your chances of mating without being eaten better.

Sticking with the Crane Fly theme, in my recent post Mammal Tracking: It’s all about paying attention, I shared a photo of this fly, a Snow Fly.

Snow Flies have six legs, but if you look carefully, you’ll notice this one only had five. As for that missing leg, Snow Flies self-amputate so that ice doesn’t enter body. It’s a fighting chance to survive the frigid winter and this photo was taking on a very cold day. An incredible adaptation.

Fast forward to today, which felt almost like summer (in the 30˚s), and I spotted another, this one with all six legs still intact.

And those two yellowish bumps on its thorax? Halteres, or small club-shaped organs, that help provide information for wing-steering muscles of True Flies (Diptera). From The Snow Fly Project, I’ve learned that “Snow flies are distinctive in their appearance, with long, spindly legs. They lack wings but do possess halteres. It has been suggested that their lack of wings might have evolved due to exposure to cold temperatures and wind (Hackman, 1964; Byers, 1983; Novak et al., 2007).”

Eventually it was time to return to our woods where I noticed more works by my friend.

Below this tree, there was even more debris and by the number of holes, it was obvious that this was a much more bountiful tree than the first one that stopped me in my tracks. That is, if you are seeking insects.

And so, I had to bend down and take a closer look. It’s like a treasure hunt at the base of a tree and let’s me know if the bird was successful in dining or not.

And I was well rewarded. All kinds of scat packages sat upon the wood chips and I knew that while the woodpecker found plenty of Carpenter Ants in the tree trunk, it had also recently dined on Bittersweet berries. As for the berries, well, um, Bittersweet does grow locally.

There was even some scat dripping off the tree! My heart be still.

As for Mr. Pileated, he’d moved on for the moment, but just before we’d parted ways earlier, he offered me a quick opportunity to spot his tongue between the upper and lower beak. Pileated Woodpeckers have sticky tongues, which they probe into the tunnels the delicious (to a woodpecker, that is) ants and other insects have created.

On this day, like so many others, I want to express my appreciation for the Pileated Woodpecker’s part in this world, for creating nesting sites that others, such as small songbirds, may use, and how he helps the trees in the forest by contributing to their decomposition, for as much as some think that these woodpeckers and their kin are killing the trees, the trees are already dying due to insect infestations, and the birds’ work will eventually help the trees fall to the ground, add nutrients to replace what they had used, and provide a nursery upon which other trees may grown.

Thank you, Pileated Woodpecker, and Bobcat, and Winter Crane Fly and Snow Fly. So many to honor.

Cool photo of pileated tongue! And nice painting!!!!

LikeLike

Thanks Sarah!

LikeLike