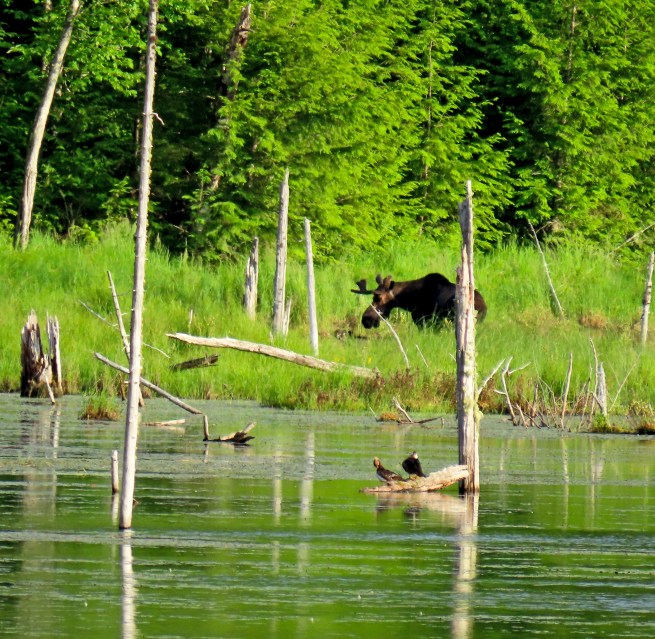

Elusive. Solitary. A rare sight. At least in my book. But I have seen them in situ, just not when I’ve had the camera ready. I’ve also seen them in captivity, which I will share.

Who are they? Our local feline carnivores: Bobcats.

At twice the size of a domestic cat, Bobcats measure about 20 to 39 inches in length and weigh anywhere from 11 to 40 pounds. That’s a huge range.

Despite the fact that I don’t often see them (they are nocturnal and I’m not so much), they leave behind prints and tracks that have led me on many an adventure, sometimes alone or in the company of others, trying to figure out the story of their behavior.

An individual print is round, and I often say about the size of a 50 cent piece, while a Domestic Cat’s print is the size of a quarter.

The cool thing about the cat’s print is that it features an indentation between the toe pads and metacarpal pad that is rather an inverted C shape. That makes it easy to remember: C for Cat. And there’s one lead toe, which helps differentiate it from the symmetrical toes of the Dog family.

Being walkers/trotters, Bobcats move through the landscape in a gait we know as Direct Registration, which has an overall straight-line-with-a-wee-bit-of-a-zigzag look. Some also know this as the footfall of a Perfect Walker.

Ah terms. There is so much vocabulary to learn when trying to understand the natural world. And . . . different authors use different terms to describe the same action. I try to stick with Print for one foot impression and Track for a series of prints, but hang out with me for a few minutes and you’ll hear me say “Track” when I’m referring to one “Print.”

Consequently, it seems like only one foot lands at a time, but actually the prints on the left represent the front and back of the left side of the body and the same on the right side. The things is, these animals are always on the hunt, well, except when they are on the lookout for a mate, and so they have to conserve energy, thus a front foot steps forward and packs the snow and the hind foot on the same side falls into the spot where the front foot had been.

And then there are those times when the track completely boggles the mind. When teaching others how to track, I try to remind them of the Three Perspectives Paul Rezendes first introduced me to in Tracking and the Art of Seeing.

What are those Three Perspectives?

- Flying: Where in the world are we? What natural community are we in? What’s the season? That sort of thing.

- Standing: What does the overall trail pattern look like?

- Lying Down: Taking an up-close and personal look at individual prints–how many toes? Shape of toes? Shape of print? Shape of metacarpal pad and heel pad? Do nails show? Taking a look from different angles is also helpful.

In the photo above, it appeared the Bobcat was moving away from me . . . and then it appeared it had move toward me. Mind you, I wasn’t there when this activity occurred, but observed it the next day. It was a simple case of the Bobcat being super conservative in its locomotion and walking on the same prints where it had already packed the snow down. Brilliant. Like Snowshoe Hare and Deer.

There are a lot of Bobcats in my neck of the woods, both behind my house, as well as on many trails that I traverse in western Maine. And trying to figure out the stories that they write is one of my great joys. Even if I can’t see the animal itself, I can try to gain a better understanding of what it was doing.

A few years ago, some of us followed one as it led us past a Porcupine high up in a Hemlock and Bear hair stuck to resin on Balsam Fir. And then we reached the broken off part of an old snag that acted as an inclined balance beam.

The Bobcat had walked all the way up the angled trunk. It’s what it did next that had us pause for a moment.

Did it cache something in this spot at the top of the trunk beam? No, it sat. For quite a while. Probably watching all the action of the woods from this vantage point. And leaving behind evidence of its warm body–melted and colored snow, plus hair.

The hair was the variegated color of a Bobcat’s. We assumed, and I think correctly, that the animal sat there for so long that the snow melted and the hair got stuck, much as it does in a Deer bed as the season goes on. For us, it was an exciting find. This wild animal had been in this very spot. For a while.

Sometimes with others and this time alone, Bobcat caches have been discovered. Bobcats like to bury the prey that they capture, and return over and over again to dig up the remains and dine.

I never did figure out what gave up its life and blood for this meal, but by the prints surrounding it and the digging that took place, I knew the creator–who had visited its pantry to enjoy a meal.

If the meal is organ meat, as those first ones usually are, the scat left behind, usually in a high spot, may be quite tarry in color and consistency.

Future scats may be full of hair from the prey . . . or even a different form of hair, that of the Porcupine’s quills. That’s exciting because we can’t always be certain of the exact meal, but sometimes clues in the scat expand the story.

Every once in a while someone tries to convince me that a Lynx passed through their landscape. I ask them to describe the animal, and they tell me mainly about the big prints left behind.

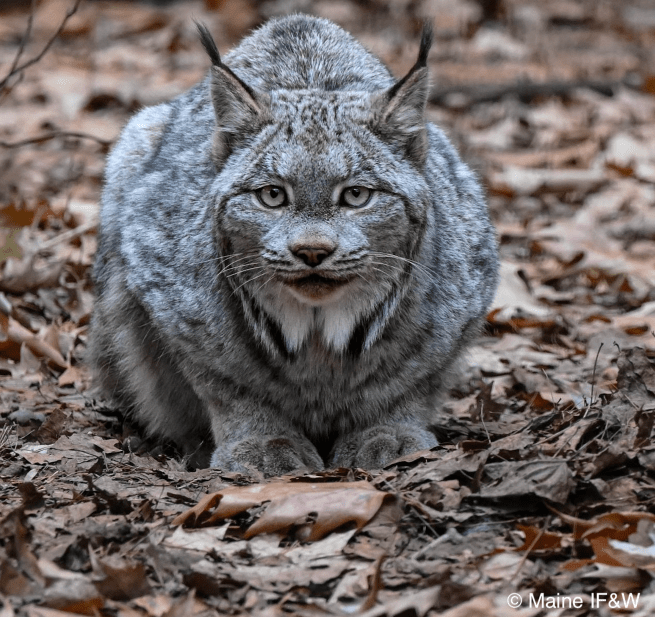

There are several ways to tell a Lynx from a Bobcat.

- A Bobcat’s tail is a wee bit longer and white at the tip and underside, while a Lynx’s tail is shorter (more bobbed actually) and black all the way around the tip.

- A Bobcat’s black ear tufts are less than an inch long, while a Lynx’s tufts are longer than an inch.

- Bobcat’s have a reddish, brownish, grayish coat, while a Lynx’s coat is mostly gray.

There are other differences, but these should help with a quick ID.

Plus, a Lynx’s diet consists of 75% Snowshoe Hare, which are best found in Boreal Forests, north of where I live. A Bobcat is a carnivore, yes, but not almost exclusively on Hares.

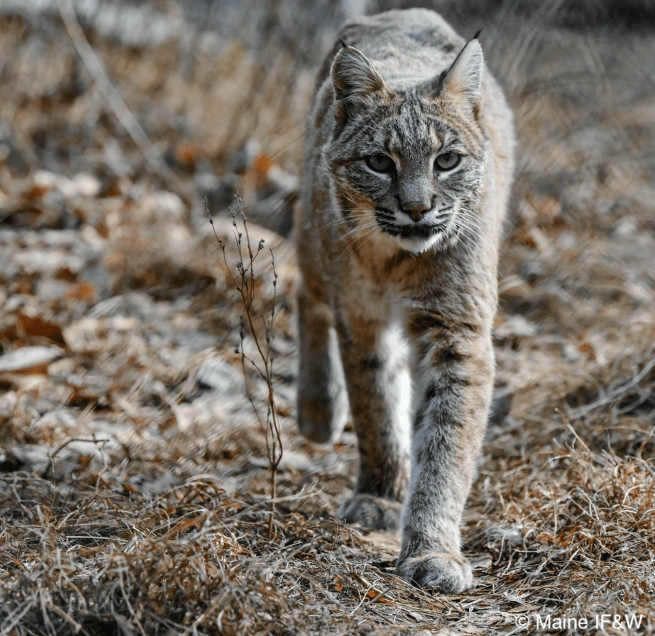

I’m grateful to Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MEIF&W) for photos they recently shared of the two species, this being a ____.

I’ll let you fill in the blank.

I’m also grateful that at the Maine Wildlife Park in Gray, Maine, and Squam Lakes Natural Science Center in Holderness, New Hampshire, the real deal animals are on display. They only have animals that have been injured or perhaps abandoned, but cannot be released back into the wild. Well, they could, but it would be instant death probably. AND . . . we get to observe these mammals and learn about them.

I’m also grateful to MEIF&W (and Laura Craver-Rogers, a current Maine Master Naturalist Program student and Education and Outreach Supervisor for IF&W), for lending me their Wildlife Trunk.

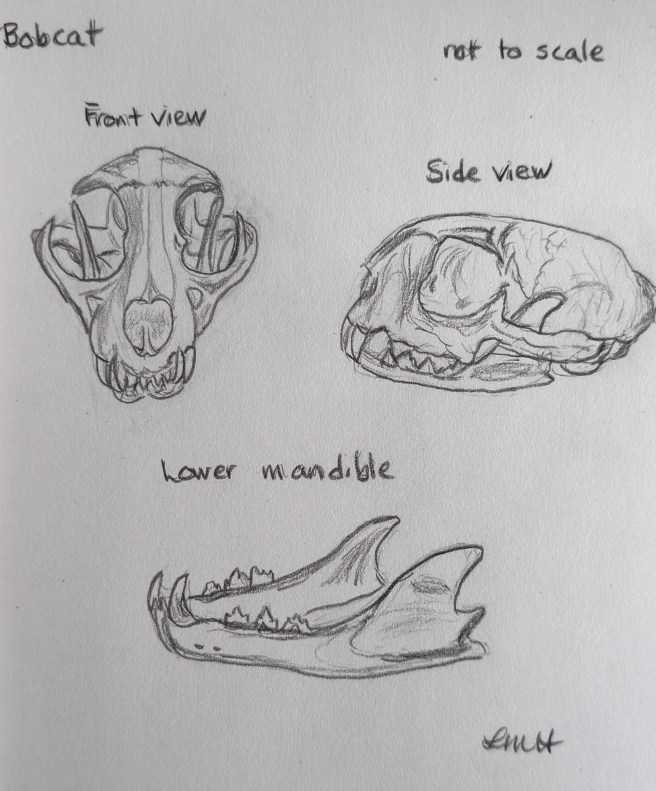

One of the critters represented by the trunk is a . . . Bobcat. Of course. It’s on the smaller size.

Do you see the tail between the two hind legs? And the white on the tip and bottom? Bingo!

And then there’s the skull with those HUGE canine teeth, and squat nose, and oh my, what big eyes you have! As the saying goes, “Eyes in front, born to hunt. Eyes on the side, born to hide.” These binocular eyes are definitely in front.

And those teeth, including the premolars and molars–meant to grind. Remember . . . true carnivore. It’s because of these teeth that there are no large bone pieces in a Bobcat’s scat.

“Here Kitty, Kitty,” shouldn’t be part of anyone’s invitation to a Bobcat. But my, what a beautiful creature. Certainly one to be revered.

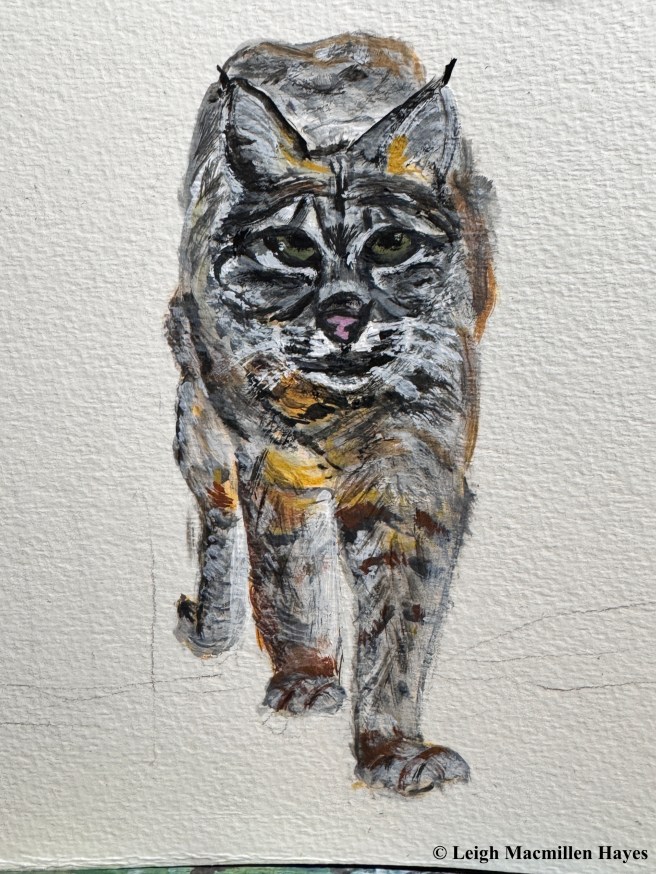

I’m trying to honor the Bobcat with a painting (and by sketching the skull). It’s a work in progress.

And I think I’ve become the object of its intention as it stares intently at me while I work on it. (I’m almost certain that since I’ve written this, I will once again see one in situ. Fingers crossed, anyway.)