I went on a reconnaissance mission today in preparation for co-leading a Loon Echo Land Trust hike in about another month–once hunting season draws to end. This particular property, like several others that they own, probably sees more people hunting and riding snowmobiles than hiking or tracking. The latter two fall into my realm and today found me doing a bit of both.

But first, I was stunned by the beauty of the ribbony flowers of Witch Hazel. I don’t know why these always surprise me, but maybe it’s the delicate petals that add bits of sunshine at this time of year when everything is else is dying back.

Their wavy-edged leaves also add color as October quickly gives way to November.

A bit farther along the first trail I followed, I found something else to stop me in my steps. Little packages of bird scat inside a hole excavated by a Pileated Woodpecker. If you follow wondermyway.com, then you know that I LOVE to find the woodpecker’s scat, but this was much smaller and I had visions of several smaller birds huddled inside on a cold autumn night.

At the end of the trail I reached a brook that flows into a river. Today, it was a mere trickle. In fact, I took this photo from the high water mark and don’t think I’ve ever seen it this low. Well, not since I began exploring this property in 2020. But then again, since then, we’ve had some heavy rain years and this year has been a bit drier.

I knew once I spotted the trickle that the nearby Beaver dam would not be working to stop the flow.

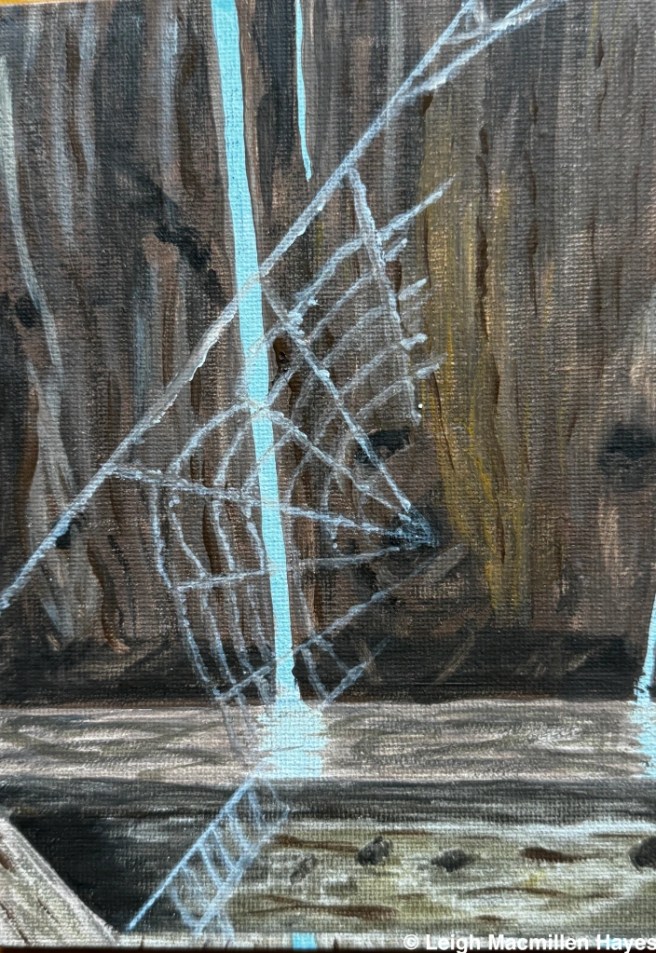

But . . . in walking over to take a look at it, I spotted something else worth noting . . .

At first my brain interpreted this disturbed site as a bird’s dust bath. Until . . .

I spotted River Otter scat. A latrine, in fact. That’s when I knew (or think, anyway–okay, assume!) that the disturbed sight was a spot where the otter rolled around, or maybe two or three did as they most often travel as a family unit.

How did I know it was otter scat? Look at those fish scales in it. And it wasn’t all that old based on the leaves under and on top of it.

Feeling like I was in the right place at the right time, I doubled back on the trail because it ends at the brook, and then turned onto another to see what else I might find. Along this one, a second brook had a better flow and had me envisioning the land trust group dipping for macro-invertebrates in this spot we haven’t explored yet.

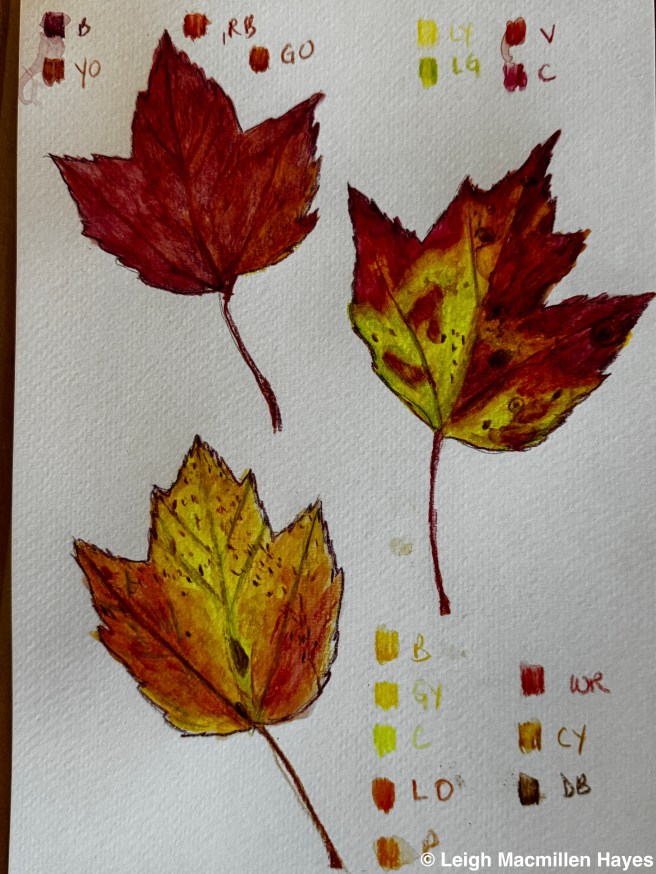

I also found another shrub that thrills me as much as the Witch Hazel. Also a shrub, I can’t pass by a Maple-leaf Viburnum in the fall without admiring its color. Mulberry? Heather? Sky-purple-pink? However you describe it, this I know–no other leaves feature these hues.

If you do spot one, take a moment and touch the leaf. I love the touchy-feely walks that are not about feelings, but rather about actually feeling something (as long as it isn’t poison ivy!).

As luck would have it, I was following an old logging road by this point, which these days serves as a snowmobile trail. Despite its uses, rocks and boulders mark sections of it. And atop one, oh my! Do you see what I saw?

A LARGE Bobcat scat and a tiny weasel scat. Could life get any better than that? I think not. Well, unless I saw the actual critters and as I write this a local friend just texted me that she and her family saw a pair of eyes reflecting in their headlights as they pulled up to their house: “I thought it was our cat from a distance. I got out to investigate. It was a bobcat! And it wasn’t afraid. I couldn’t believe it! It was so close. I could see the face. I ran inside to get a flashlight. It just watched us as we watched it.” ~Amanda.

If she was someone else, she’d jump on social media and inform the world that the big bad wolf is in the neighborhood because that seems to happen any time someone spots a Bobcat or Fisher. But, she appreciates the gift of the sighting and I’m so thankful for that.

Back to my Bobcat, or rather Bobcat scat–it was classic! Segmented, tarry, and no bones. Ahhhh! What dreams are made of–at least my dreams.

It was also quite hairy. Squirrel? Snowshoe hare? Weasel? Pop goes the weasel? Into the Bobcat’s mouth? I’ll never know. But I love that one marked the rock in the middle of the trail and the other followed suit. And I also love how that one piece stands upright like a tower. I don’t think I’ve ever spotted such a presentation before.

No, don’t worry, we don’t have yet. But I took this photo of a Bobcat print, also classic in presentation, along the same trail last February. Same critter? Offspring? Sibling? Any of the above.

At last I reached what would become my turn-around point, again on an out-and-back trail. And once again, I slipped off the trail and made my way toward an expansive wetland that is actually part of the small brook I’d crossed.

Old Beaver works, such as this American Beech with a bad-hair day from stump sprouting, were evident everywhere.

Other Beaver sculptures created a few years ago as indicated by the dark color of heartwood where the rodent had gnawed and cut the tree down, probably to use as building material, now sport fungi in decomposition mode.

In the wetland, I spotted two Beaver lodges, both featuring some mud for winter insulation. There were two other larger lodges with no mud, so I suspect these are the residences of choice for this year.

I also spotted a Beaver channel, but could find no new work on the land.

That surprised me given that there was new wood on top.

I could have walked farther along the wetland and may have spotted some freshly hewn trees, but when I spotted several Wood Ducks on the far side, I decided to stand still for a bit because they are easily spooked.

And my grand hope was that if I was quiet, I might get treated to a Beaver sighting. Or two.

For a half hour I waited. Nada. And so I climbed back up to the trail and walked out.

But, I was present in the moment today and received so many gifts, which may or may not be there when I bring others to explore. That’s okay, because together we’ll make other discoveries.

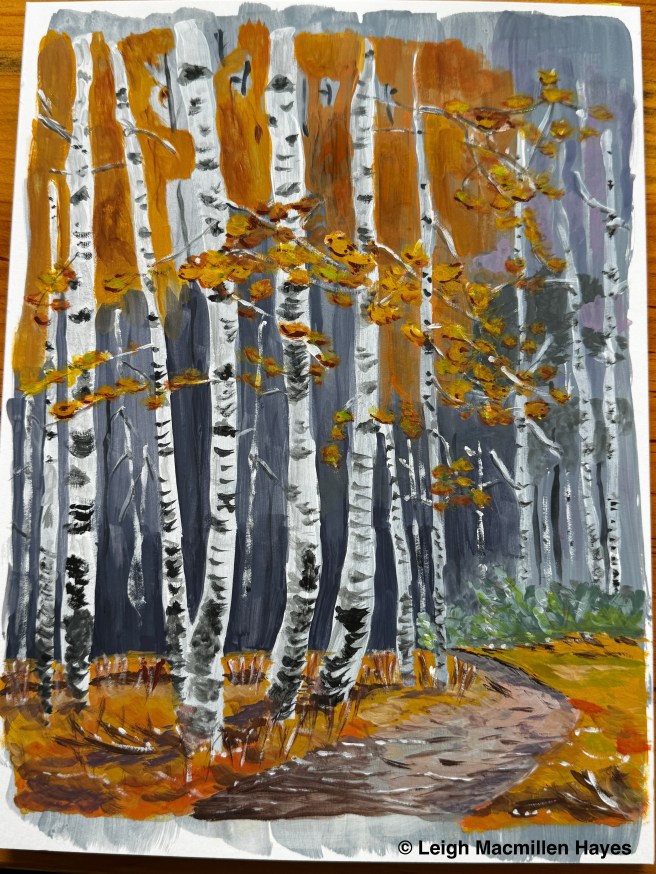

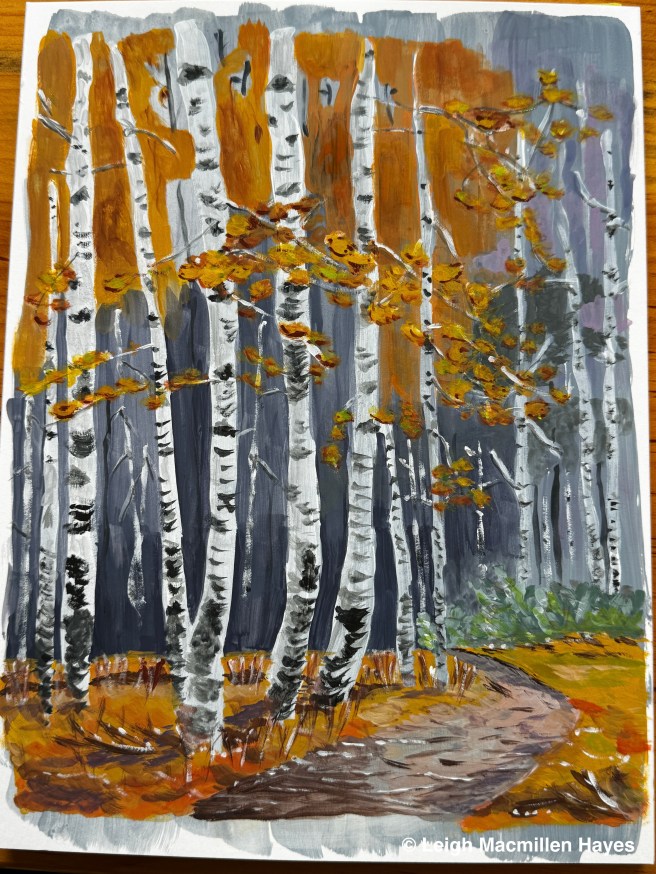

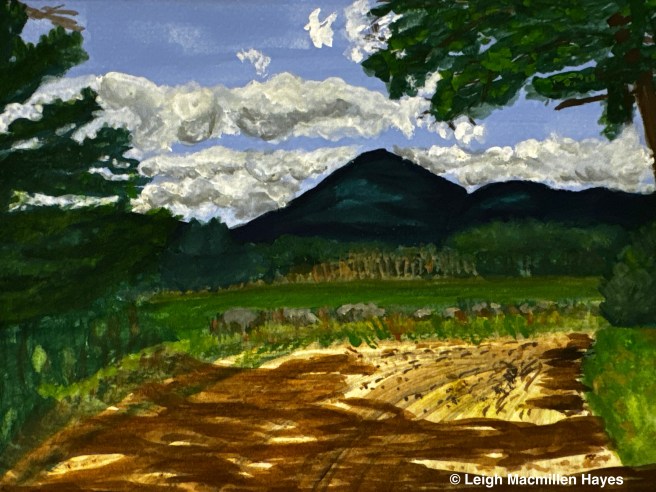

Thanks for stopping by, once again, dear readers. I leave you with this painting as a parting gift for being so faithful in following me as I wander and wonder.