Thank you to all who read and comment and share wondermyway.com. Some of you have followed my blog posts since the beginning, February 21, 2015. A few have joined the journey as recently as yesterday. I’m grateful for the presence of all of you in my life.

To mark this occasion, I thought I’d reflect upon those moments when my wonder gave me a glimpse of the “Thin Places” that I’ve experienced either by myself or in the company of others.

To quote my friend, Ev Lennon, “A Thin Place is a spot of beauty, loveliness, space–an example of the wideness and grandeur of Creation.”

I think of them as places that you don’t plan a trip to visit, but rather . . . stumble upon.

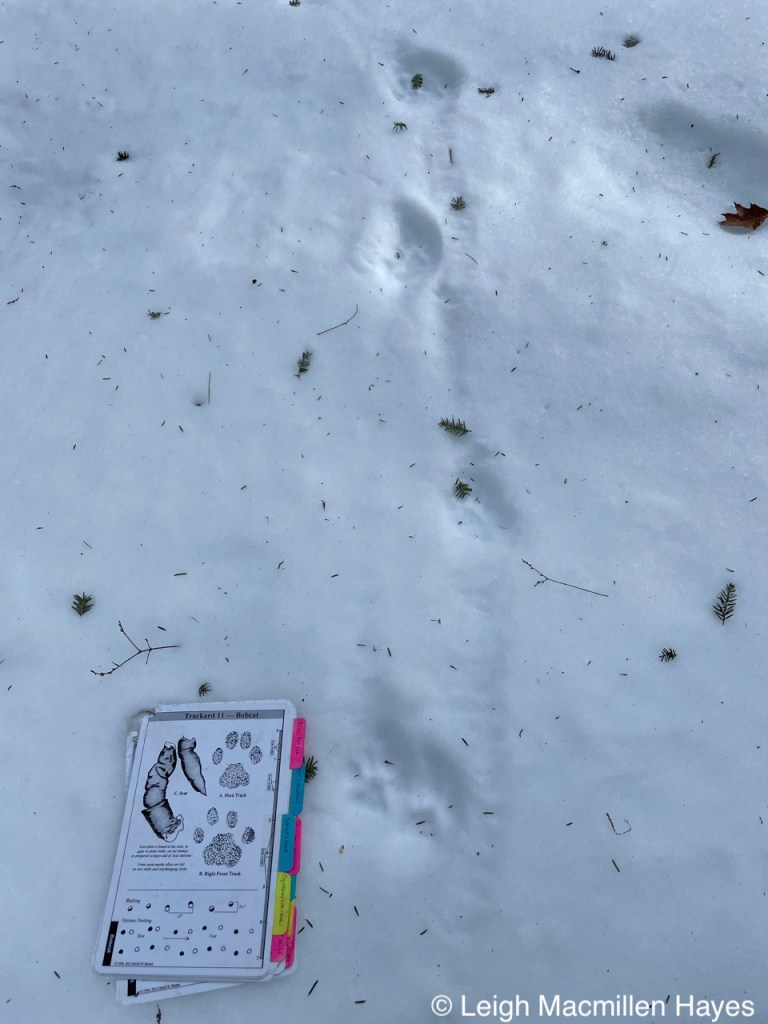

I had

the track of

a bobcat to thank,

for it showed me the way

to a special friend.

It was without expectation

that we met

and spent at least

an hour together.

And then I realized

though its sight is not great,

it was aware of my presence

and I hightailed it home,

but I will always

celebrate time spent

with the Prickly Porcupine.

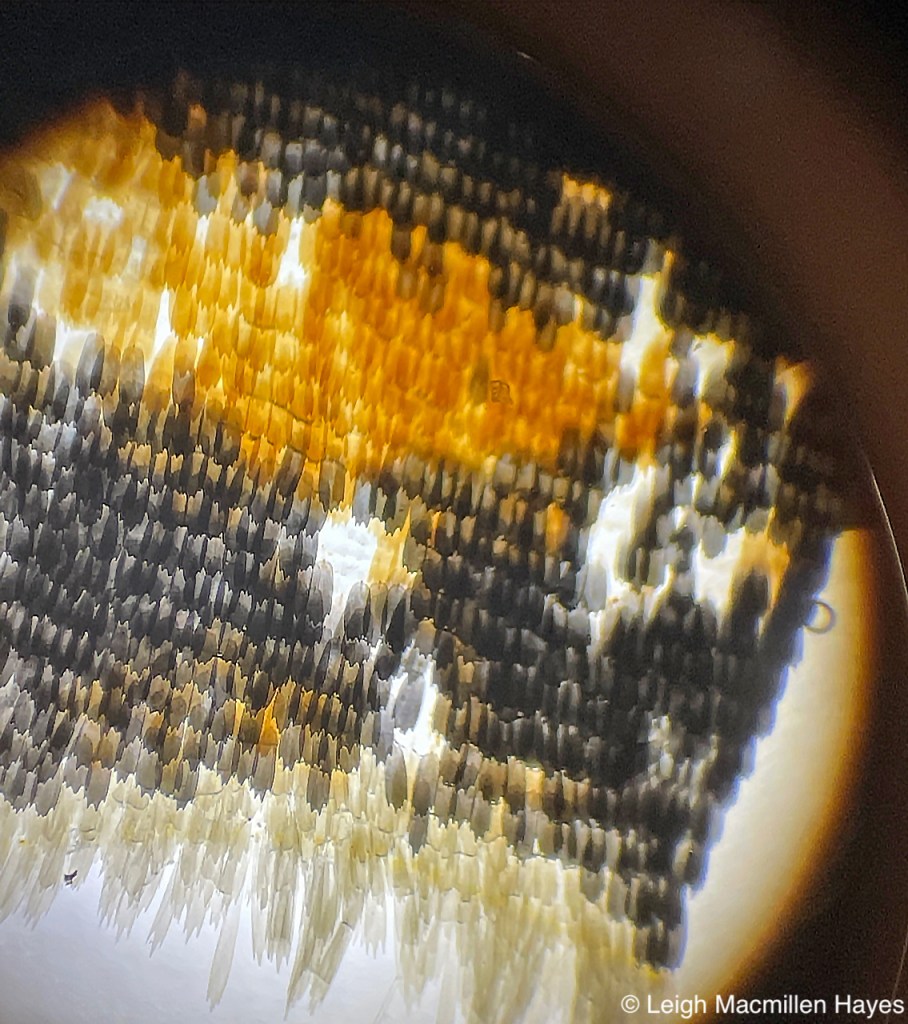

Something quite small

scurrying across the snow

captured my attention

and suddenly

there was a second

and a third

and then hundreds

of Winter Stoneflies.

All headed west from the brook

toward mature tree trunks

to beat their drum-like structures

against the bark

and announce their intentions to canoodle.

Though I could not hear

their percussion instruments,

I am grateful

to learn

with those who

march to the beat of a different drummer.

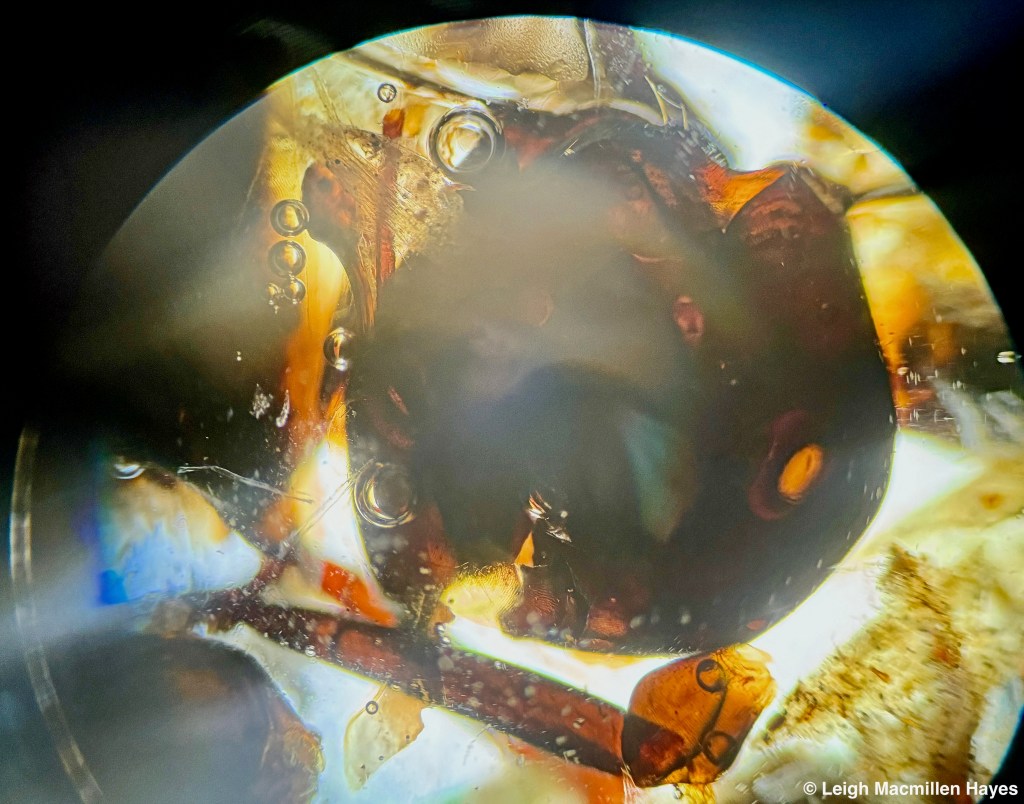

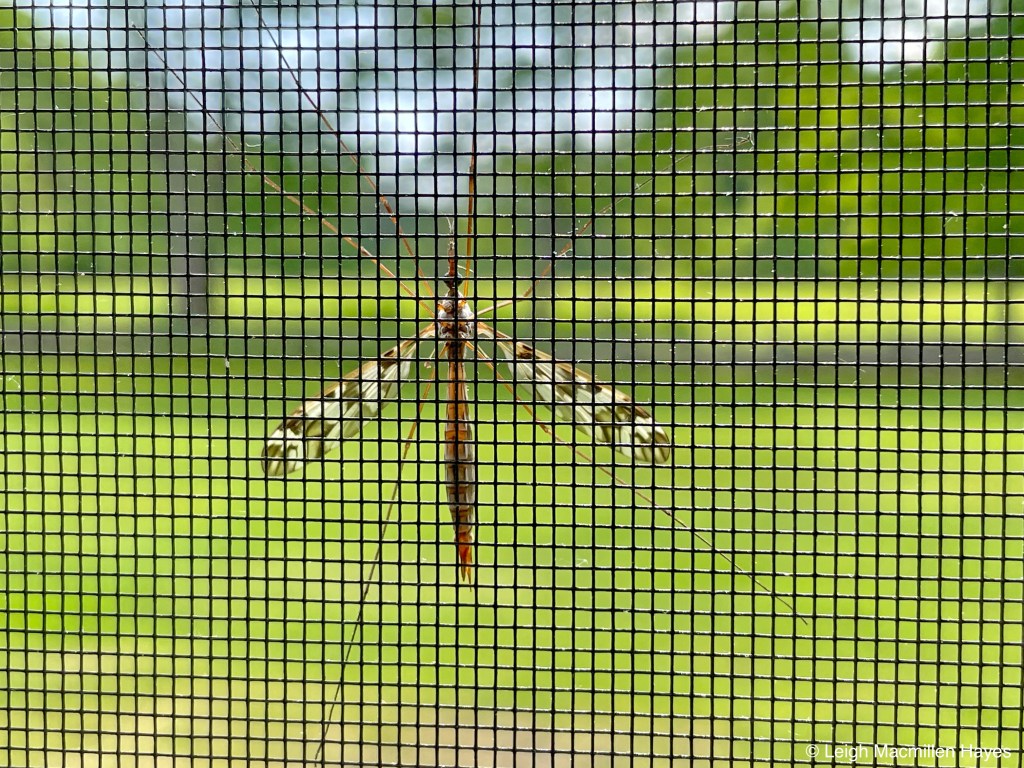

Standing beside quiet water,

I was honored

on more than one occasion

to have my boot and pant legs

considered the right substrate

upon which to transform

from aquatic predator

to teneral land prey

before becoming

a terrestrial flying predator.

It takes hours

for the dragonfly to emerge

and I can't think of a better way

to spend a spring day

than to stand witness

as the mystery unfolds

and I begin to

develop my dragonfly eyes

once again.

It took me a second

to realize that I was

staring into the eyes

of a moose,

and another second

to silently alert My Guy

while grabbing my camera.

She tip-toed off

as we relished our time

spent in her presence

and at the end of the day

had this Final Count

on a Moosed-up Mondate:

Painted Trillium 59

Red Trillium 3

Cow Moose 1

One was certainly enough!

Some of the best hours

I spend outdoors

include scanning

Great Blue Heron rookeries

to count adults and chicks

and get lost in the

sights and sounds

of rich and diverse wetlands.

Fluffy little balls

pop up occasionally

in the nests and the

let their presence be known

as they squawk

feverishly for food.

And in the mix of it all

Nature Distraction

causes a diversion of attention

when one swimming by

is first mistaken for a Beaver

but reveals its tail

and morphs into a Muskrat.

I give thanks to the Herons for these moments.

What began as a "Wruck, Wruck" love affair

continued

for longer than usual

and due to

a rainy spring and summer

I was treated to a surprise

in the form of developing frog legs.

In the midst of my visits

one day I heard

the insistent peeps

of Yellow-bellied Sapsucker chicks

demanding a meal on wings,

which their parents

repeatedly provided.

Walking home

from the pool

another day,

I was honored

to spend about ten minutes

with a fawn,

each of us curious

about the other

until it occurred to me

that its mother

was probably nearby

waiting for me to move on,

so reluctantly I did,

but first gave thanks

that something is always happening

right outside my backdoor.

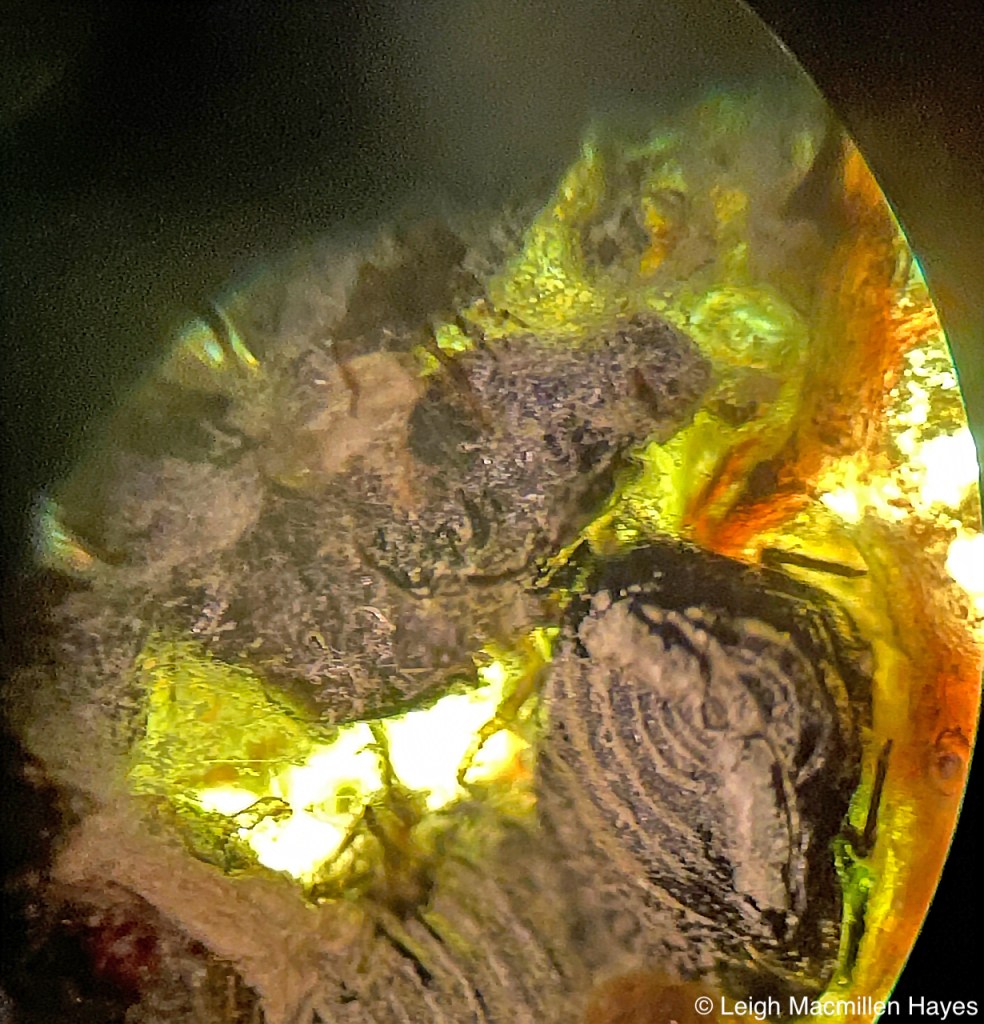

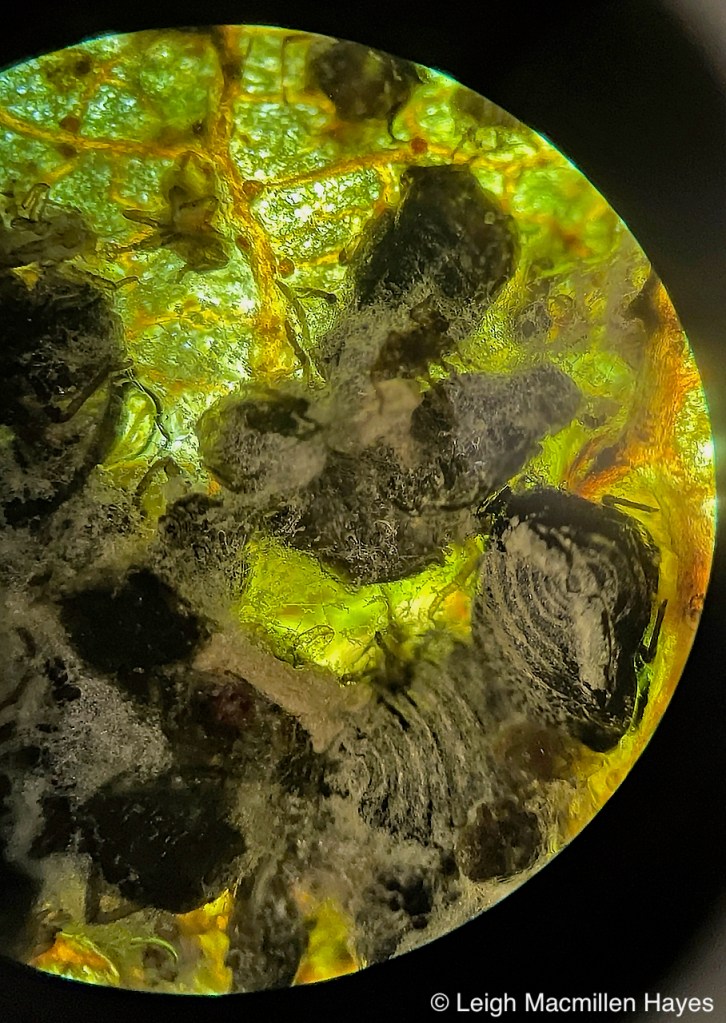

While admiring shrubs

that love wet feet,

I counted over

one hundred branches

coated with white fluffy,

yet waxy ribbons.

Theirs is a communal yet complex life

as the Woolly Alder Aphids

suck sap from Speckled Alders.

Communal in that

so many clump together

in a great mass.

Complex because

one generation reproduces asexually

and the next sexually,

thus adding diversity

to the gene pool.

Along with the discovery

of coyote scat,

and Beech Aphid Poop Eater,

a fungus that consumes

the frass of the Aphids,

it was an omnivore, herbivore, insectivore kind of day.

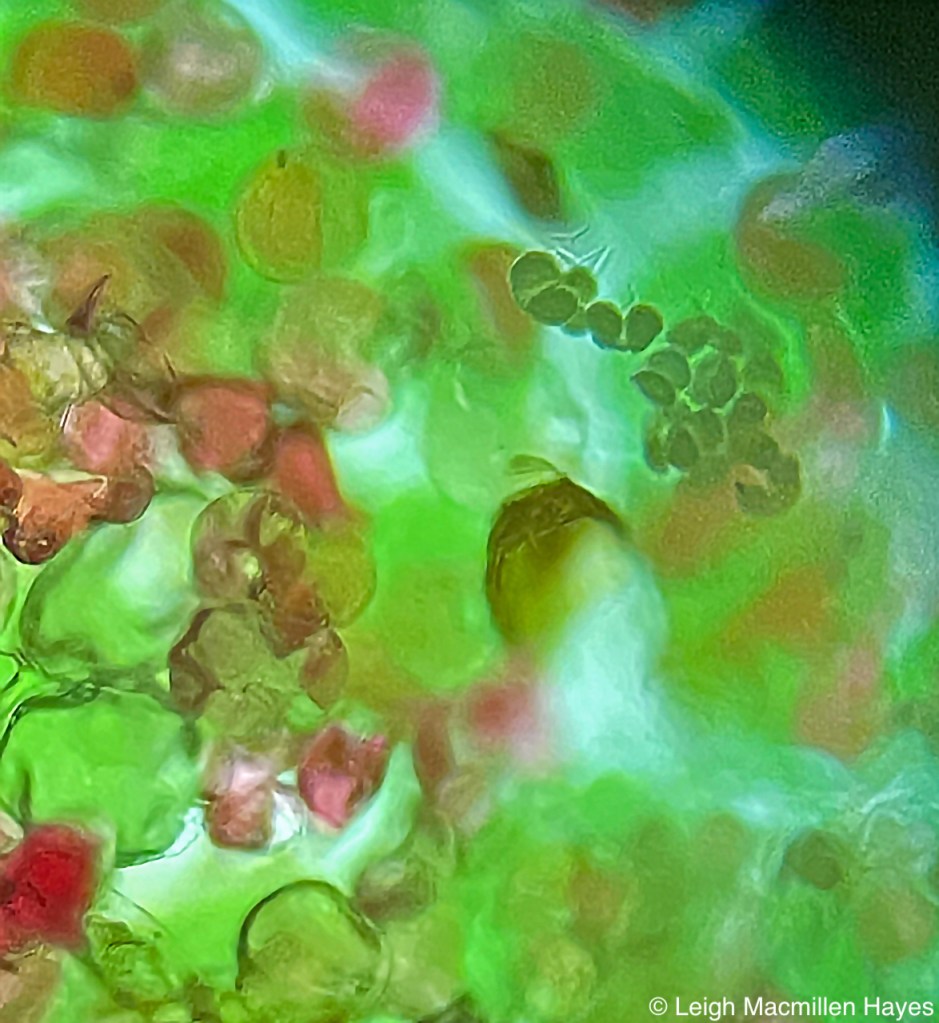

Awakening early,

a certain glow

in the sky

pulled me from bed

and I raced downstairs

to open the door

and receive the quiet

that snowflakes create.

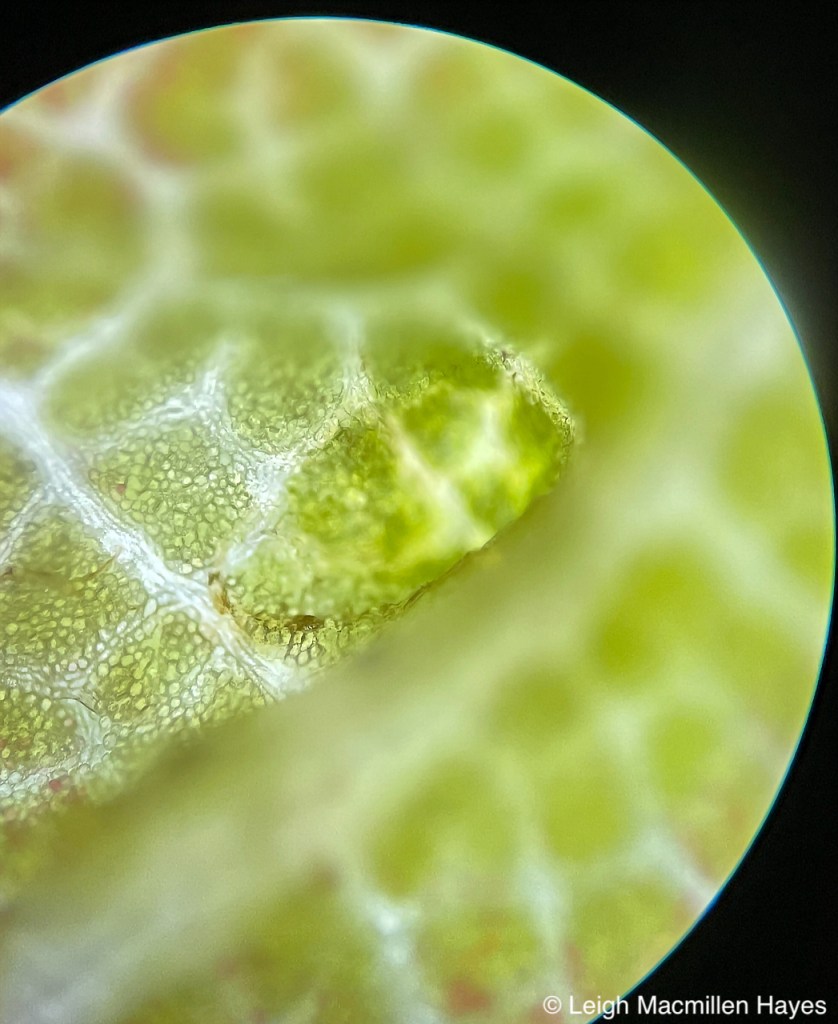

The snow eventually

turned to rain,

which equally mesmerized me

as I watched

droplets elongate

and quickly free fall,

landing on bark below

in such a manner

that caused them

to mix with sap salts and acids.

The result was

White Pines foaming

in the form of

Pine Soap

with its hexagonal shapes:

worth a natural engineering wonder

and I gave thanks for being present.

Occasionally,

it's the action

outside the backdoor window

that keeps me standing sill

for hours on end,

as a variety of birds fly

in and out

of the feeding station,

such as these Purple Finches,

the males exhibiting

bad hair days.

Bird seed is not

just for birds

as the squirrels prove daily.

And White-tailed Deer

often make that

statement at night.

But this day was different

and they came

in the morning

using their tongues

to vacuum the seeds all up.

At the end of the day,

my favorite visitors

were the Bluebirds

for it was such a treat

to see them.

But it was the mammals

who made me realize

not every bird has feathers.

These are samples

of the Thin Places

I've stumbled upon

this past year.

They are a

cause for celebration,

participation,

and possibility.

My mind slows down

and time seems infinite

as I become enveloped

in the mystery.

I give thanks

that each moment

is a gift

and I have witnessed

miracles unfolding

that did not

seek my attention,

but certainly captured it.

And I thank you again

for being

one of the many

to wander and wonder my way.