We knew not what to expect when we met this morning. My intention was to visit a structure of unknown use, then follow a trail for a bit before going off trail and mapping some stone walls. Curiosity would be the name of the game and friends Pam and Bob were ready for the adventure when I pulled into the trailhead parking lot.

We traveled rather quickly to our first destination, pausing briefly to admire only a few distractions along the way–if you can believe that.

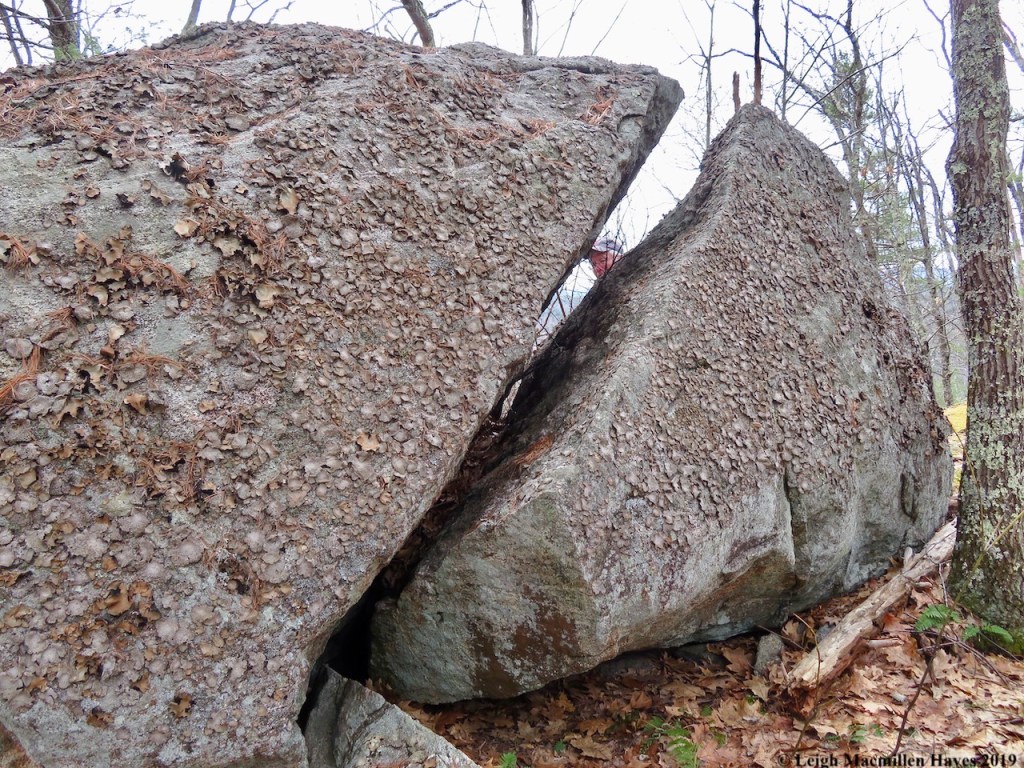

It’s a stone structure on the back side of Amos Mountain. Three years ago we visited this site with Dr. Rob Sanford, a University of Southern Maine professor and author of Reading Rural Landscapes. At that time we came away with so many questions about this structure located on a mountainside so far from any foundations. Today, we still had the same questions and then some.

Who built it? What was it used for? Was there a hearth? Did it have a roof? Was it ever fully enclosed? Was there originally a front wall? Could it be that it extended into the earth behind it? Was it colonial? Pre-colonial?

Why only one piece of split granite when it sits below an old quarry?

And then there’s the left-hand side: Large boulders used in situ and smaller rocks fit together. One part of the “room” curved. For what purpose?

Pam and Bob stood in the center to provide some perspective.

And then I climbed upon fallen rocks to show height.

We walked away still speculating on the possibilities, knowing that we weren’t too far from a stone foundation that belonged to George Washington and Mary Ann McCallister beginning in the mid-1850s and believed the structure to be upon their “Lot.”

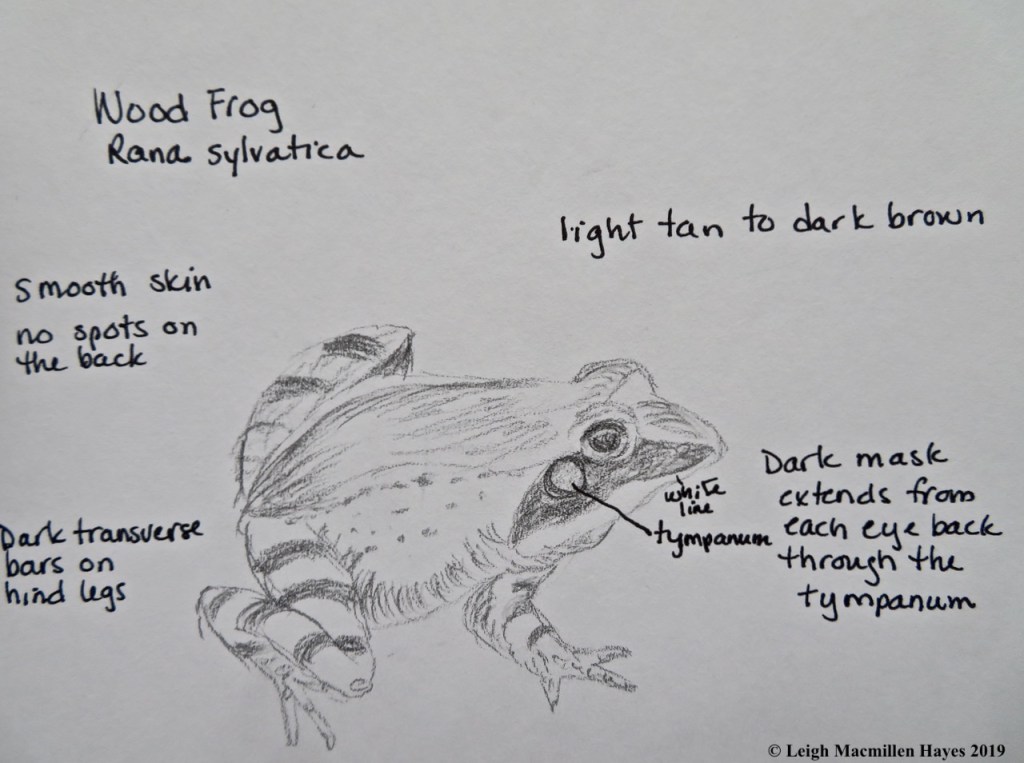

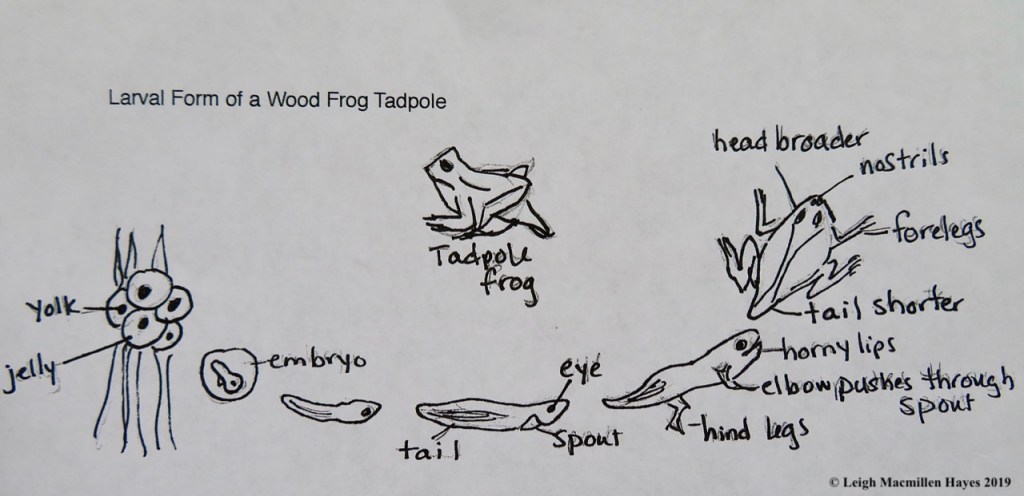

As we continued along the trail, we spied several toads and a couple of frogs. Their movement gave them away initially, but then they stayed still, and their camouflage colorations sometimes made us look twice to locate the creator of ferns in motion.

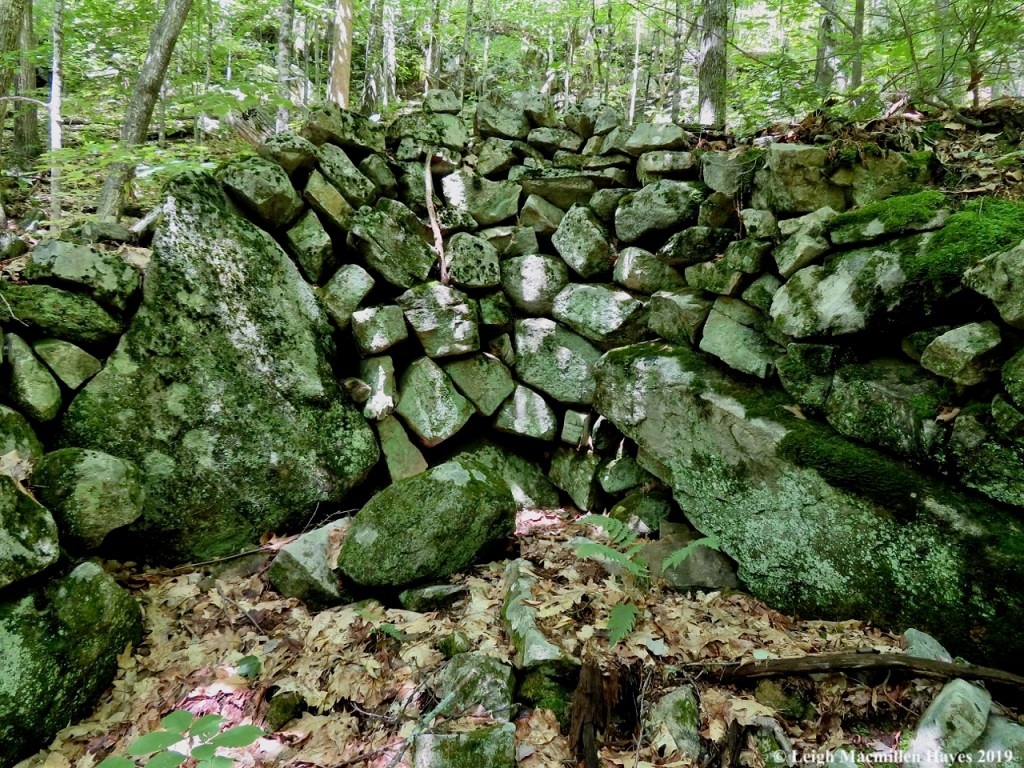

At last we crossed over a stonewall that we assumed was a boundary between the McAllister property and that of Amos Andrews. It was the walls that we wanted to follow as there are many and our hope was to mark them on GPS and gain a better understanding of what seems like a rather random lay out.

The walls stand stalwart, though some sections more ragged than others. Fallen trees, roots, frost, weather, critters and humans have added to their demise, yet they are still beautiful, with mosses and lichens offering striking contrasts to the granite. Specks of shiny mica, feldspar and quartz add to the display.

The fact that they are still here is a sign of their endurance . . . and their perseverance. And the perseverance of those who built them.

But the fashion of these particular walls has stymied us for years. As we stood and looked down the mountain from near the Amos Andrews foundation, we realized that the land was terraced in a rather narrow area. And so we began to follow one wall (perspective isn’t so great in this photo) across, walk down the retaining wall on the right edge and at the next wall follow it across to the left. We did this over and over again and now I wish I’d counted our crossings, but there were at least eight.

Mind you, all were located below the small root cellar that served as Amos Andrews’ home on and off again beginning in 1843.

And below one of the terraced walls just beyond his cellar hole, there was a stoned off rectangle by the edge. Did it once serve as a foundation for a shed?

Had Amos or someone prior to him tried to carve out a slice of land, build a house, and clear the terraced area for a garden?

It seems the land of western Maine had been forested prior to the 1700s and there was plenty of timber to build. A generation or two later, when so much timber had been harvested to create fields for tillage and pasture, the landscape changed drastically, exposing the ground to the freezing forces of nature. Plowing also helped bring stones to the surface. The later generation of farmers soon had their number one crop to deal with–stone potatoes as they called them. These needed to be removed or they’d bend and break the blade of the oxen-drawn plowing rake. Summer meant time to pick the stones and make piles that would be moved by sled to the wall in winter months. Had the land been burned even before those settlers arrived? That would have created the same scenario, with smaller rocks finding their way to the surface during the spring thaw.

As it was, we found one pile after another of baseball and basketball size stones dotting the landscape. Stone removal became a family affair for many. Like a spelling or quilting bee, sometimes stone bees were held to remove the granite from the ground. Working radially, piles were made as an area was cleared. Stone boats pulled by oxen transported the piles of stones to their final resting place where they were woven into a wall.

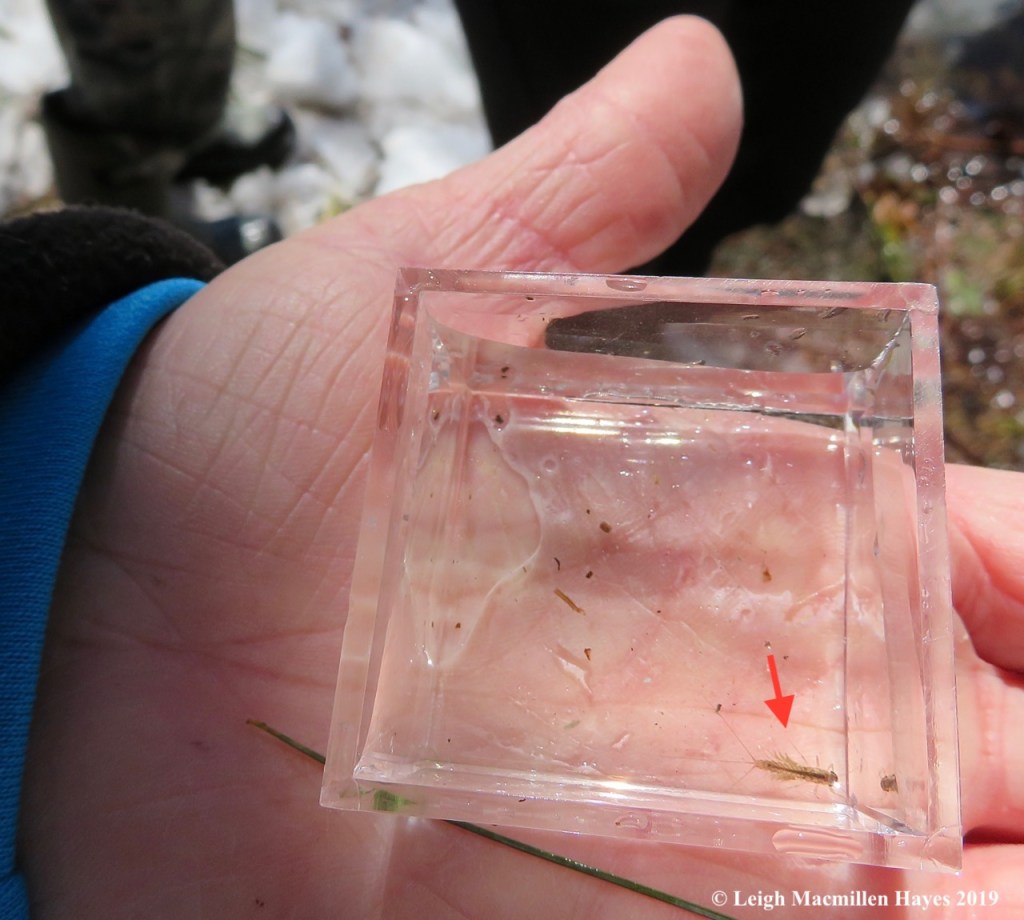

Occasionally, however, we discovered smaller stones upon boulders. Were they grave markers? Or perhaps spiritual markers?

There were double-wide stone walls with big stones on the outside and little stones between, indicating that the land around had been used for planting. But why hadn’t all the piles been added to the center of these walls? That’s what had us thinking this was perhaps Pre-colonial in nature.

Pasture walls also stood tall, their structure of a single stature. I may be making this up because I’ve had an affinity with turtles since I was a young child and own quite a collection even to this day, but I see a turtle configured in this wall. Planned or coincidence?

My turtle’s head is the large blocky rock in the midst of the other stones, but I may actually be seeing one turtle upon another. Do you see the marginal scutes arching over the head? Am I seeing things that are not there? Overthinking as my guy would suggest?

I didn’t have to overthink when I spotted this woody specimen–last year’s Pine Sap with its many flowered stalk turned to capsules still standing tall.

And a foot or so away, its cousin, Indian Pipe also showing off the woody capsules of last year’s flowers, though singular on each stalk.

As we continued to follow the walls, other things made themselves known. I do have to admit that we paused and pondered several examples of this plant because of its three-leaved presentation. Leaves of three, leave them be–especially if two leaves are opposite each other and have short petioles and the leader is attached between them by a longer petiole. But, when we finally found one in flower we were almost certain we weren’t looking at Poison Ivy. I suggested Tick-Trefoil and low and behold, I was correct. For once.

Our journey wandering the walls soon found us back on what may have been a cow or sheep path and it was there that we noted a cedar tree. Looking at it straight on, one might expect it to be dead. But a gaze skyward indicated otherwise. Still, the question remained–why here?

A Harvestman Spider may have thought the same as it reached out to a Beech Nut. After all, the two were located upon a Striped Maple leaf.

Onward we walked, making a choice of which way to travel each time we encountered an intersection of walls. This one had a zigzag look to it and we thought about the reputation Amos Andrews had with a preference for alcohol. But . . . did Amos build all or any of these walls?

We continued to ponder that question even as we came upon a stump that practically shouted its name all these years after being cut, for the property we were on had eventually been owned by Diamond Match, a timber company. Do you see the mossy star shape atop the stump? And the sapling growing out of it? The star is actually a whorl–of White Pine branches for such is their form of growth. And the sapling–a White Pine.

And then . . . and then . . . something the three of us hadn’t encountered before. A large, rather narrow boulder standing upright.

Behind it, smaller rocks supported its stance.

The stone marked the start of another stone wall. And across from it a second wall, as if a road or path ran between the two and Bob stood in their midst adding coordinates to his GPS.

We chuckled to think that the stone was the beginning of Amos’ driveway and he’d had Andrews written upon it. According to local lore, he had a bit of a curmudgeon reputation, so we couldn’t imagine him wanting people to stop by. The road downhill eventually petered out so we didn’t figure out its purpose. Yet.

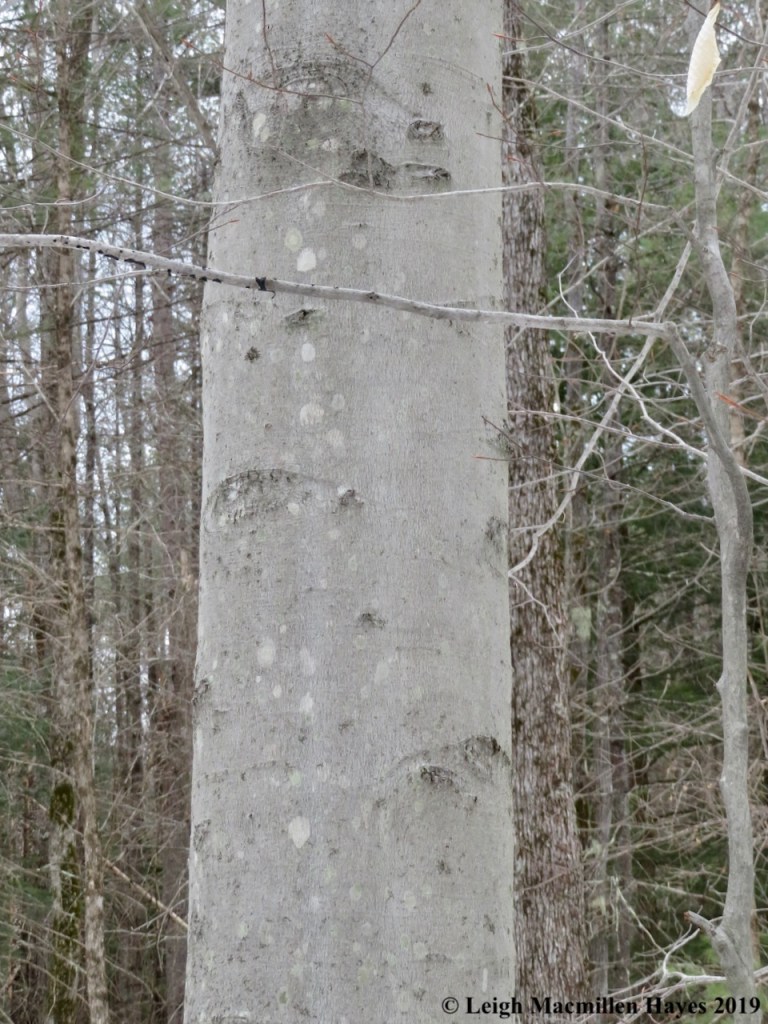

In the neighborhood we also found trees that excited us–for until ten months ago we didn’t think that any White Oaks existed in Lovell. But today we found one after another, much like the piles of stones. With the nickname “stave oak,” it made sense that they should be here since its wood was integral in making barrels and we know that such for products like rum were once built upon this property.

Trees of varying ages grow quite close to Amos Andrews’ homestead.

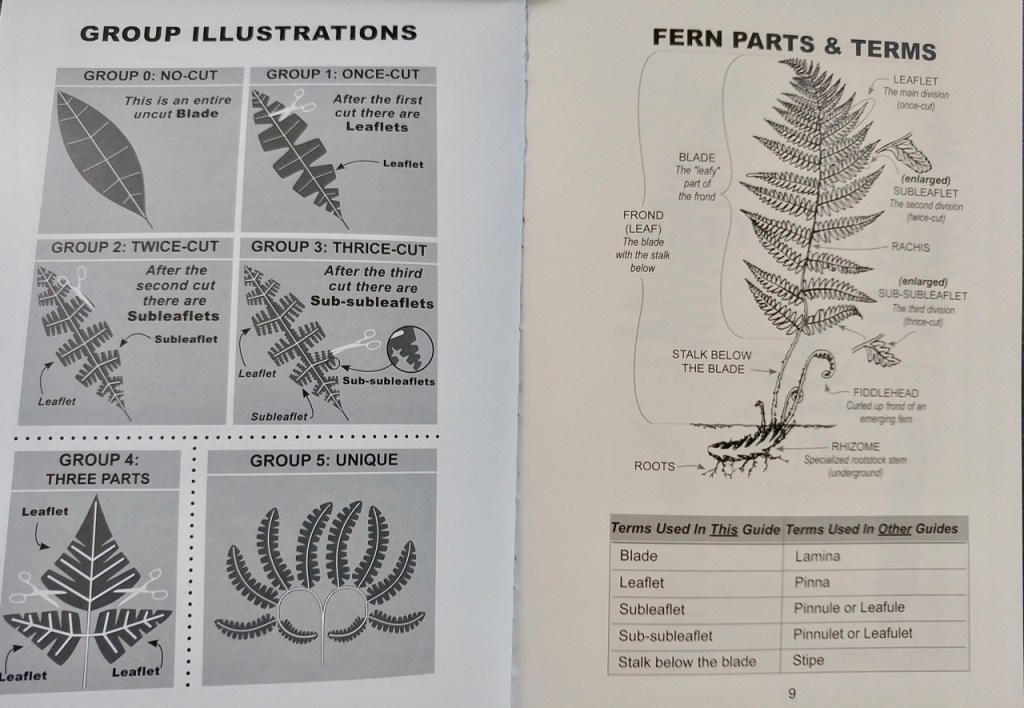

Also growing in the area was Marginal Wood Fern, its stipe or stalk below the blade covered with brown scales and fronds blue-green in color, which is often a give-away clue that it’s a wood fern.

We know how it got its name–for the round sori located on the margins of the underside of the pinnules or leaflets. Based on their grayish-blue color, they hadn’t yet matured. But why are some sori such as these covered with that smooth kidney-shaped indusium? What aren’t all sori on all ferns so covered?

So many questions. So many mysteries.

As curious as we are about the answers, I think we’ll be a wee bit disappointed if we are ever able to tell the complete story of the stone structure and the upright stone and all the walls between.

Walking among mysteries keeps us on our toes–forever asking questions and seeking answers.