Last night one of the Greater Lovell Land Trust‘s volunteer docents earned her certification from the Maine Master Naturalist Program. The MMNP’s goal is to develop a statewide network of volunteers who will teach natural history throughout Maine. With hands-on training, the course provides over 100 hours of classroom and outdoor experience, focusing on geology, identification of flora and fauna, wetland and upland ecology, ecological principles and teaching methods. By the time students complete the program, which includes a final capstone project, they have developed the skills to lead a walk, present a talk and provide outreach. In the year following certification, each graduate agrees to volunteer 40 hours and thereafter must continue to volunteer to remain an active Maine Master Naturalist.

And so it was that Juli joined four of us in the GLLT’s docent group by becoming a certified naturalist last evening. And today, she was out doing what she does best–leading homeschooled families along a GLLT trail. You see, for her capstone project Juli created a group called Nature Explorers. On the second Tuesday of each month (and today’s was the third trip she’d led for this group), other homeschooled families join hers for a walk with a focus along a GLLT trail. Today’s focus: Signs of Spring.

Given the fact that the snow is still at least knee deep, we knew it wasn’t going to be easy. But the day dawned bright, if a bit chilly to start, and so two of Juli’s kids waited for others by hanging out with the trees. Or rather . . . in the trees.

Once all had gathered, she led us down Slab City Road to the trailhead for the Heald and Bradley Ponds Reserve.

It was there that while we began our search for the season that often begins with a stubborn start in western Maine , we spied something that brought smiles to our faces and awe to our experience. Otter slides. On both sides of Mill Brook. Look carefully and you may also notice the slides–they look like troughs in the snow.

We tromped through (leaving our snowshoes behind, which we sometimes regretted) to take a closer look, noticing where the mammal had bounded and then slid down the embankment.

And then we moved on . . . to observe and learn, including fifty cent words like marcescent, which means withering but remaining attached to the stem. Juli pointed out the dried up leaves on the beech trees.

And the kids joined her to take a closer look–at the leaves, but also the buds, which had started to swell. Ah, sign one!

It was a Witch-Hazel which next grabbed the group’s attention. She explained that while the small, gray woody structures looked like flowers, they were really capsules that go dormant throughout the winter. Those will develop over the next growing season and then in autumn forcibly expel two shiny black seeds about 10 to 20 feet.

One of the boys noticed that the buds were hairy and so others came in to examine the structures.

From there, it was another beech tree to check out, but this time the discussion moved toward the alternate orientation of its branches and leaves.

And then, because they suffer from the best of syndromes we refer to as Nature Distraction Disorder, the group stopped at a Red Pine to admire its bark.

With hand lenses, they focused on the various colors of the thin, puzzle-like scales. Some had fallen to the ground as is the habit of the flakey bark, but Juli reminded everyone that it’s best not to pull it off for bark protects the tree much like winter coats protect us.

It was a fungi that next attracted the group.

And so they pulled out the lenses again to look at the spore surface of several Birch Polypores growing on downed trees. The brownish underside was actually another sign of the season for they would have released their spores in late summer or autumn.

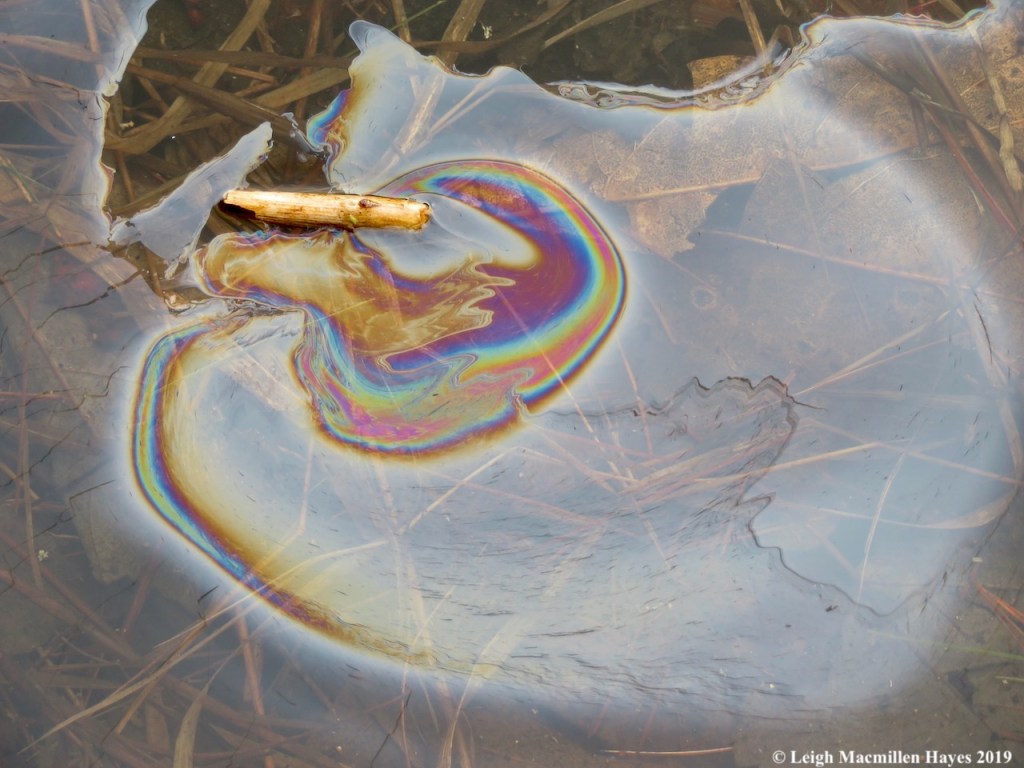

A wee bit further and a wet spot was noted where we could see some brown leaves reflecting the names of trees in the canopy above, but also, drum role please . . .

some greenery with buds beginning to form–in the shape of Wintergreen. One of the girls did point out that though it was a sign of the season, it did have the word “winter” in its name.

Another one of the girls looked up at an old Pileated Woodpecker excavation site, and noted the spider web within that had been created last summer by a funnel-web spider, so named because of the funnel-shaped web. Though no one was home today, the spider typically waits in the funnel for prey to fall onto its horizontal web. Then it rushes out, grabs its victim, and takes it back to the silken burrow to consume and hide in wait.

Since our signs were few and far between, and Juli really wanted to get to Otter Rock to show some fun finds, she challenged the kids to run with her.

They did. And then they slid.

And looked.

And spotted.

And wondered.

And wondered some more.

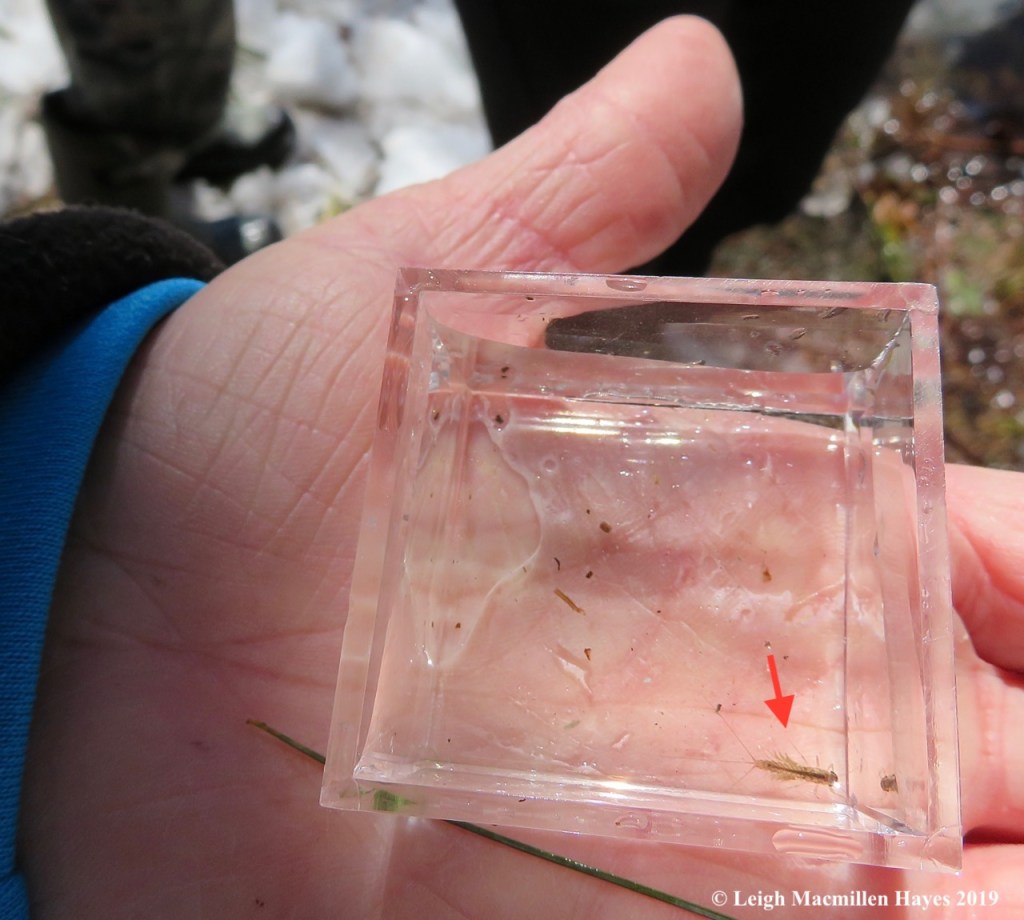

We’d reached our destination of Otter Rock and though we didn’t have any dipping containers, we made do with lucite bug boxes.

At the edge of Heald Pond, the kids found movement in the water . . .

in the form of Mayfly Larvae, with fan-like gills along the abdomen and three filaments at the tip.

Spring indeed! With that discover, we left with a spring in our steps, already looking forward to next month’s vernal pool exploration.

P.S. Thanks Juli for this wonder-filled offering, and congratulations on your achievement. You are now a member of the nexus of naturalists.