The older (and possibly wiser) I grow, the more gratitude I find in my heart for all those who have paved the path for me. Beginning with my parents, who first grounded us in the natural world, sending my siblings and me out to play and not giving us limits so we could go to places like City Mission and Lost Pond to ice skate in the winter, and follow the old trolley line to the town dump or in the opposite direction in the summer, and certainly disappearing behind the houses across the street from us and down to the brook any time of the year, as well as taking us on long walks in the woods and along the Connecticut shoreline and encouraging us to learn–always.

And then there have been so many others who have crossed my path and I dare not name them for fear of leaving some out, but knowing that there were those who were obvious teachers for me, and others who I didn’t realize were such at the time, but I still came away with lessons learned–to all of them I give my heartfelt thanks.

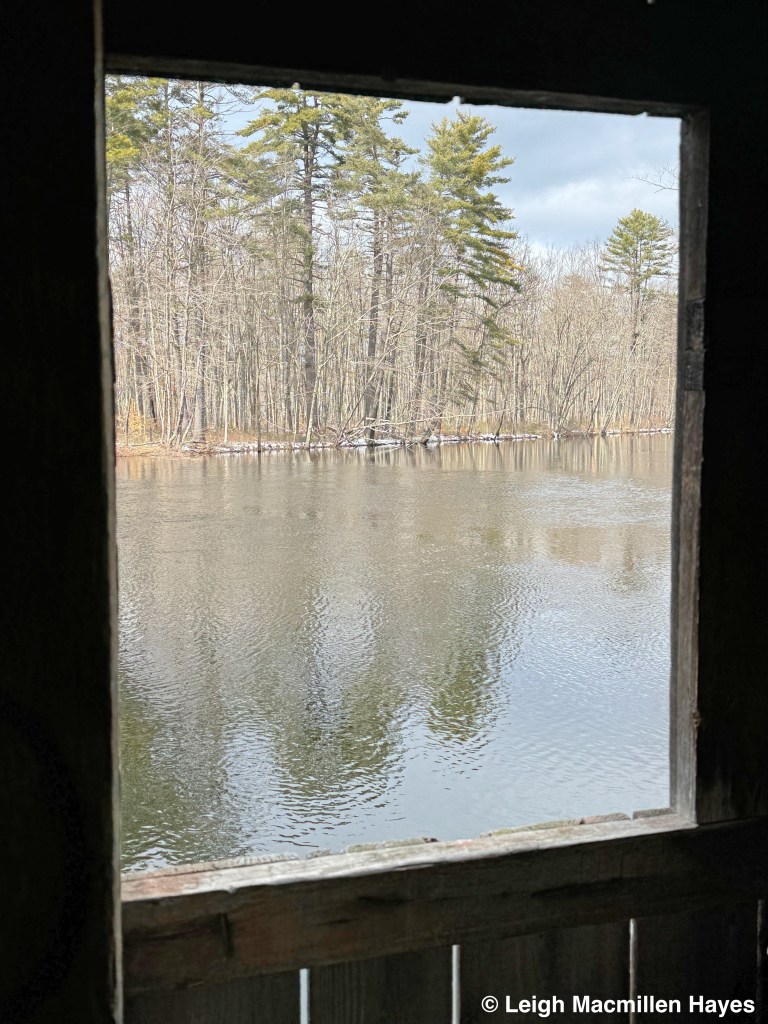

Some lessons have involved the big picture view of the world, no matter how cold the temperature and frigid the wind.

Other lessons have been much subtler, like realizing that ice forms in a perpendicular manner and fans out behind a culvert that spews water at the formation of a river.

And then there have been reviews of old lessons, where the Black Bears leave no telephone pole untouched. The shiny numbers are invitations encouraging the bears to turn their heads and then pull upper incisors toward lower, mangling both the wood and metal.

And then to leave a signature scratch above this work of art.

And in the midst of this action, to accidentally deposit a bit of hair on the mangled wood. (Please note that My Guy was surprised that I can still feel such glee looking at the same poles year in and year out, but I reminded him that each year I find changes, including hair on different poles and this year the scratch marks on several that I don’t recall seeing in the past or simply failed to notice. What’s not to love? )

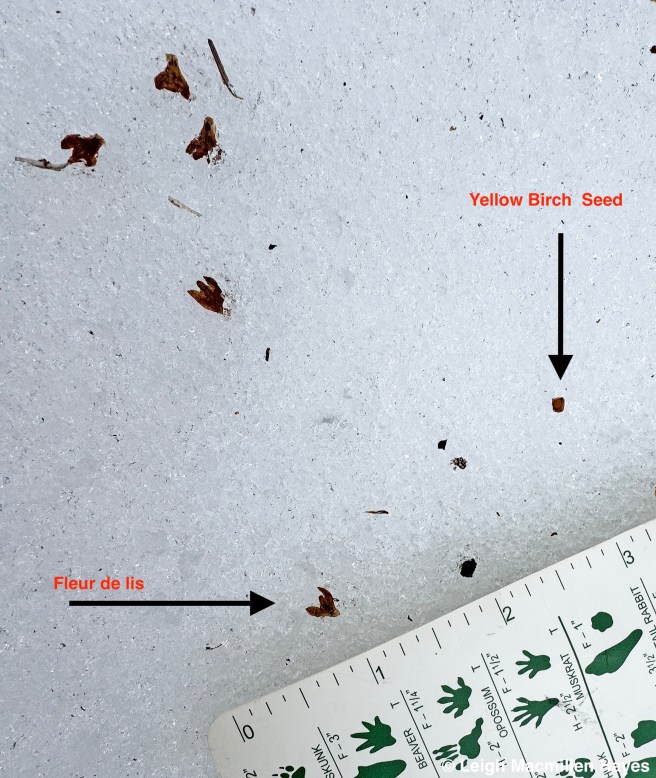

There are other old lessons that are also worthy of review–especially as once the snow flies I begin to see them written everywhere I look.

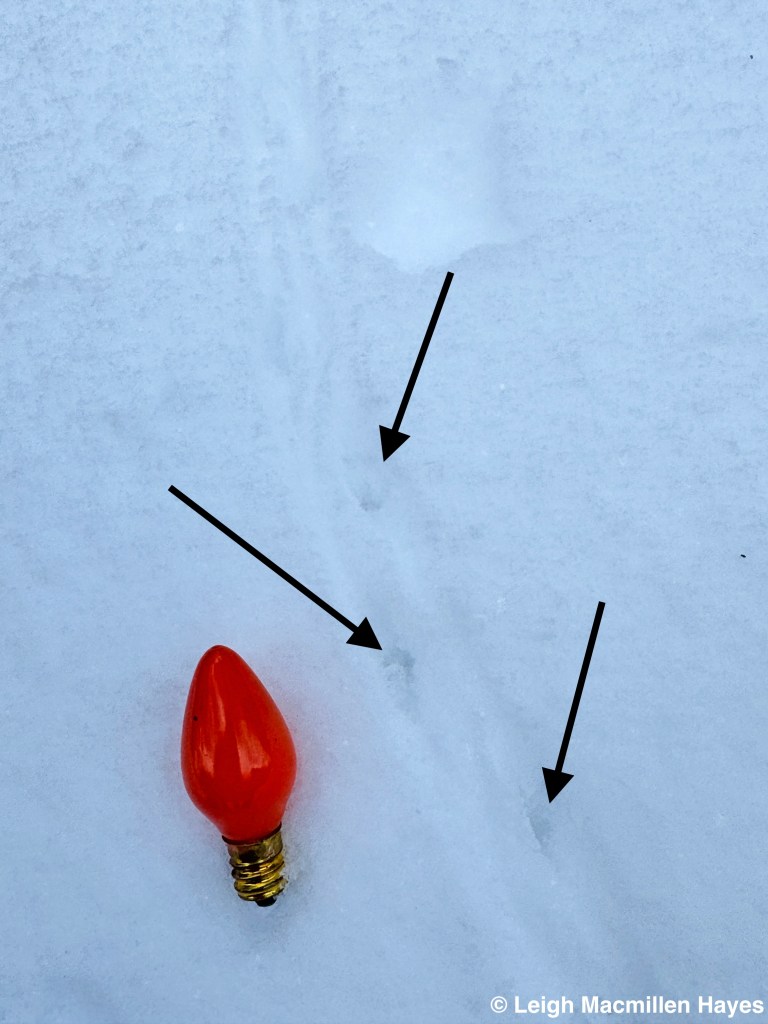

This one is the track of the Ermine or Short-tailed Weasel. I love how each set of prints represents four feet, the front two landing and then as this bounder’s hind feet begin to fall into place, the front feet lift off toward the next spot. One of the biggest give-aways to the creator is the diagonal orientation of each set of prints. Sometimes the diagonal changes, but it’s almost always present.

And just sometimes the same weasel decides to take it easy between sets of prints and goes for a quick slide, creating what is known to some as a Dog Bone and to others as a Dumbbell. I think it’s easy to see both once you know you recognize the behavior, but I can’t tell you how many years it took me to actually see this.

And then, along a wetland shoreline, another member of the weasel family reminded me that occasionally they like to slide much like a River Otter, but this being was a Mink!

And not to be left out of the scene, a Fisher (not a Fisher Cat–ah, but the hairs go up on the nape of my neck). The diagonal is there and though this was a quick shot and not all the details are visible, all Mustelids (weasels) have five toes and all are bounders.

Red Foxes also write lessons in the snow and I followed this one for quite a ways, finding a spot where it pounced, though I’m not sure it caught the intended meal because there was no evidence of a struggle.

While its overall trail was the zigzag of an animal that double packs a spot because the hind foot typically steps where the front foot had already been, sometimes the trail zags more than it zigs and I imagine he was looking for another food source.

Occasionally he changed his pace and I had to wonder why–did he smell or hear something that I couldn’t discern?

One thing I could easily discern–his territory marking. Fox urine! On a sapling. Skunk-like in odor. All classic during mating season, which we are in. Mind you, I learned this summer that Red Fox urine always smells skunky, but it’s even more so in the winter.

And I’m here to report that the Red Squirrel that crossed his path lived. For the moment anyway.

The final lesson of old, though hardly the final lesson, was the realization that some rather large prints were actually signals of two-way traffic. Do you see the upside down C in middle print? This is the neighborhood Bobcat crossing an ice bridge. But . . . which way is he walking?

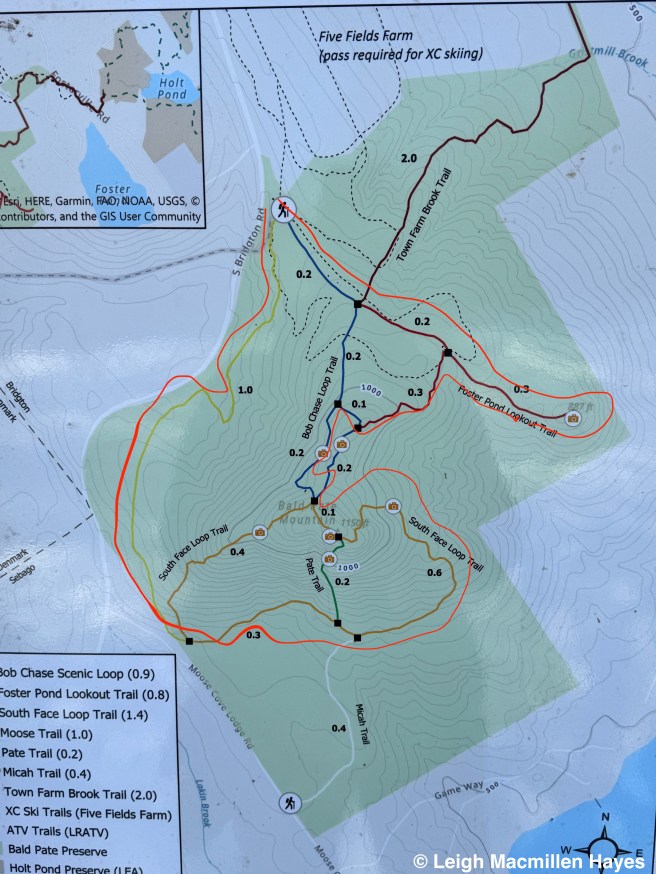

Turns out in both directions. East and West. Packing the snow in one direction with both front and back feet and then following the same exact trail back. I remember the first time I saw this sort of behavior when I was looking for evidence of a Bobcat and a Coyote in a local watershed prior to offering a summer presentation to a lake association. It was about thirteen years ago and I think of it every time we hike the same trail at Five Kezar Ponds Reserve in Stoneham. First I knew I was following the Coyote and then I realized that a Bobcat had walked in the opposite direction on the Coyote’s prints. The same thing happened at Dan Charles Pond Reserve in Stow a few years ago. You can read about it in The Tail of Two Days.

Look carefully at the photo above. Do you see it? The better to reserve energy.

While I love reviewing old lessons because there’s always something new to observe or a better understanding of the animals behavior is gained, new lessons are even more exciting.

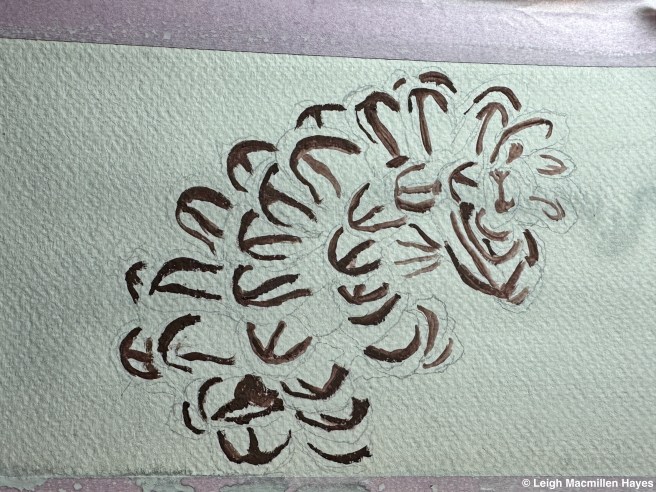

And tada, this is one. A Red Squirrel’s territorial mark.

The bark is nibbled and striped and a scent post is left behind letting others know who inhabits this particular area. This is the first I’ve found, but now that I’ve seen it, I can’t wait to locate more.

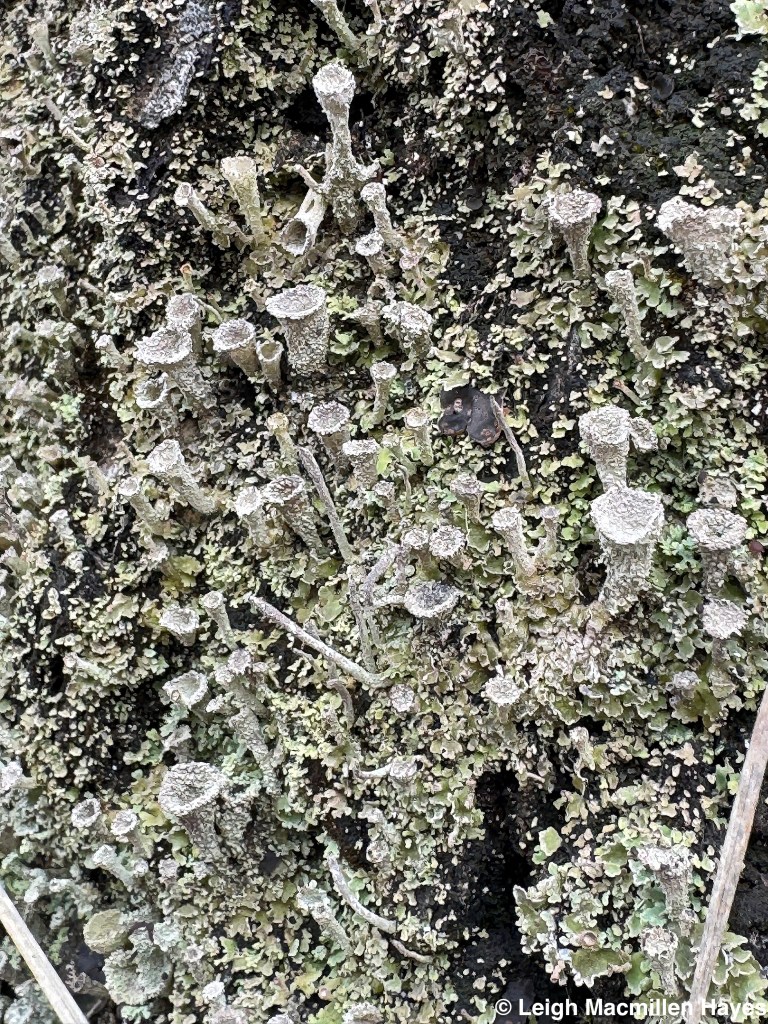

Another new lesson–discovering a Funnel Weaver Spider walking on the snow. Oh, I know that some spiders have Gylcerol that allows them to do this and I’ve seen sooo many, but a Funnel Weaver? Was it a bad decision? I’ll never know. So far, though, this is the only Funnel Weaver I’ve encountered this winter.

And then there have been sweet treats–not really lessons, though at some level everything is a lesson. But three times this past week I’ve spotted Red Crossbills–twice while participating in Maine Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count and once beside a local road where they’ve overwintered for years.

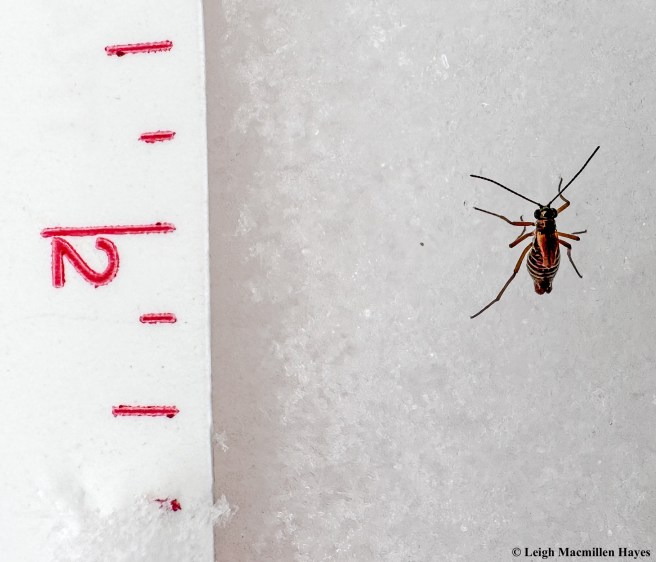

And . . . while the world view is important, sometimes it’s the teeny tiny things that need to be acknowledged–as in the case of this Snow Scorpionfly. I still can’t believe I spotted it. The snow was rather icy, so my ruler was sliding about, thus the positioning. But it’s there to give you a sense of this small insect’s size.

At the end of the day, or week, or hike, or blog post, my heart speaks a million words of gratitude to all of those who have helped me find my way, naturally.

I know I’m blessed.

I know how fortunate I am to have a curiosity about the natural world.

I know my desire to learn is a lifelong gift.

And I can only hope that in some small way, I can share my learnings with you.