I walked out the door this morning and wandered down one trail and then another and intended to go farther into the woods, but as often happens, I was stopped in my tracks.

On granite at my feet, covered as it was with lichens of the crustose and foliose sort, I spied a rather large specimen of scat. High point. Center of trail. Classic.

Based on the size and hair and bones packed within, I knew the creator: a coyote. If I awake during the night I can sometimes hear the family members calling to each other, the youngsters learning to hunt so they’ll be ready when they disperse.

The trail narrowed by a small stream and I was wearing my muck boots so proceeded at will. It’s been a few months since I’ve traveled this way and was surprised at how grown in it had become this summer. While the Sugar Maples do not like wet feet from all the rain we’ve had, other species have thrived, including the Red Maples, and this shrub that bordered each side of the trail.

It’s leaves still entact showed off that they are doubly toothed in a rather random order. So each little “tooth” is like the edge of a saw, but if you look closely, you’ll note that there are bigger teeth made up of a series of smaller teeth before the leaf margin cuts in toward the main vein and then heads out again to form the next bigger tooth made up of smaller teeth. And those veins in between the main vein and those that lead to the margin–reminded me of the crinkles on an apple doll person, since it is apple season.

The leaf buds, which form in the summer for next year, are hairy and have only two scales. Because of recent warm weather, at least one decided to jump the gun and open now rather than waiting until next spring. I’ve seen that with other plants of late, including Blueberry, Daylily, Sheep Laurel, and Partridgeberry.

Others who best not jump ahead are the catkins of this species, the longer green and red being the male pollen carriers that will slowly elongate over the winter and turn more yellowish red in the spring. The female flowers are tiny magenta catkins located just above the males.

Once the females are wind pollinated, the males will drop off and the females will form into a fruit that resembles a cone.

The name of these shrubs, if I haven’t already spilled the beans, is Speckled Alder, so named for the white dots (think lenticels for gas exchange) that populate the bark. These shrubs love wet feet, which is why they are growing on either side of that small stream.

Some of the Speckled Alder cones hide beneath tongues imitating piles of snakes stretching out, made from galls caused by an infection to increase the surface for spores from a fungus to spout. It’s a smart strategy.

I also found a few Lady Beetles today, including one larval form. They were on these shrubs for one reason.

That reason being the Woolly Alder Aphids who live a complex life in which they alternate between a generation reproducing asexually (no guys, just gals), and one reproducing sexually with both males and females adding to the diversity of the gene pool. The males and females fly to Maple trees to canoodle, but those found on the Alders are all female.

They live such a communal life as they suck sap from the shrub, that one might think this entire mass is just one insect. Hardly. And do you see all that waxy wool that covers their bodies? If you watch these insects for even a few seconds, you’ll note that the hairs move independently. It’s almost otherworldly.

Since they’ll overwinter, I think of the wool as providing a great coat. In the summer, ants, and now Lady Beetles, and even a few other insects farm them to get the aphids to excrete honeydew from the sap.

The aphids don’t harm the the shrubs, but I saw so many today that that fact is hard to believe. I gave up on counting branches but over one hundred played host.

That said, there was another character in the mix. Do you see the top branch that leans out to the right?

The sweet honeydew I mentioned forms a substrate for a nonpathogenic fungus called sooty mold that blackens leaves and bark beneath colonies of aphids. The mold is known scientifically as Scorias spongiosa or, my favorite and drum roll please . . . Beech Aphid Poop-Eater: A fungus that consumes the scat (frass in insect terms) of a Beech Blight Aphid (not the same as Beech Scale Insect that causes Beech Bark Disease). Alders are in the Beech family.

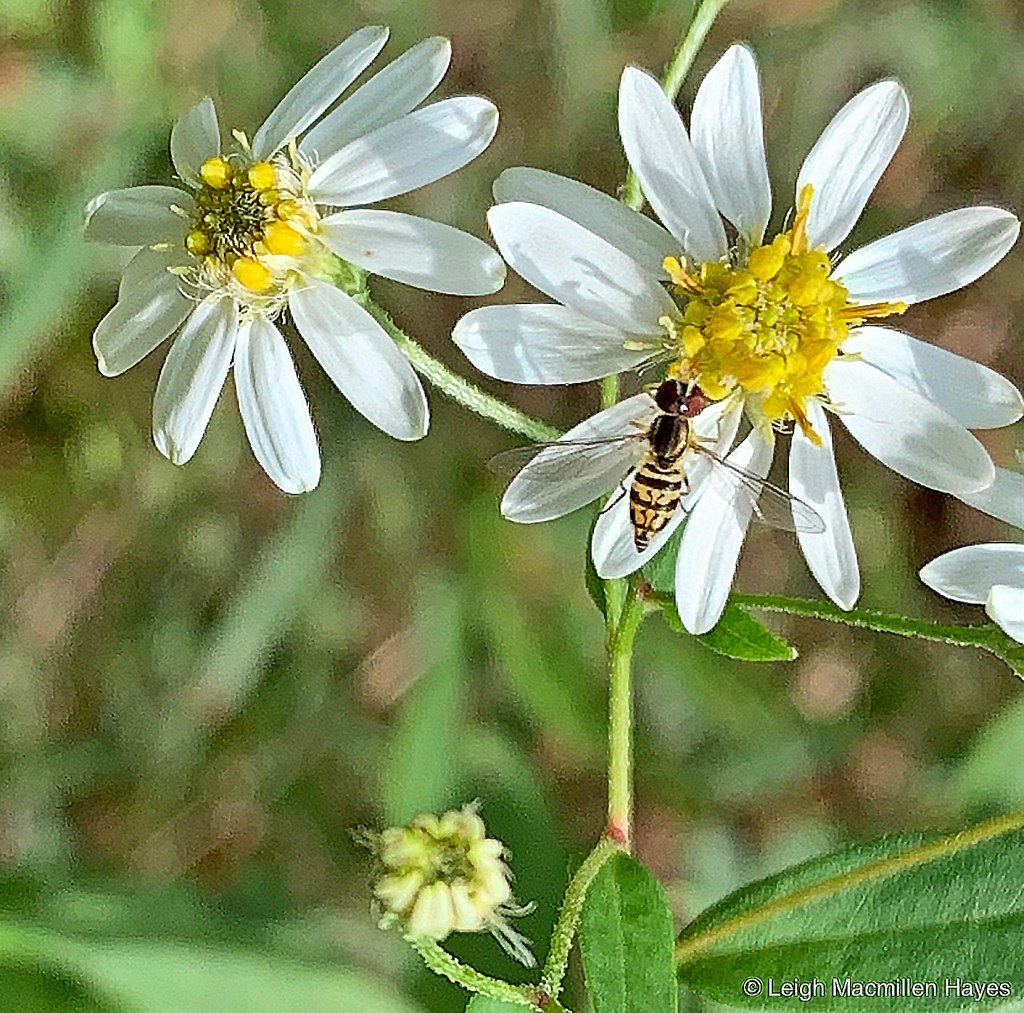

As I left a few Autumn Meadowhawk Dragonflies flew ahead of me on the path. They’re days are numbered, so I’m always thrilled to see them flying and posing.

Omnivore, Herbivore, Insectivore, Oh MY! And all of this within a ten-foot stretch of the trail.