The other day a friend and I made plans for an upcoming hike. Before saying goodbye, she said, “Don’t forget to bring your tree book.”

Really? I have at least thirty books dedicated to the topic of trees. But . . . I knew exactly which one she meant: Forest Trees of Maine. I LOVE this book–or rather, booklet. You’ll notice the tattered version on the left and newer on the right. Yup, it gets lots of use and often finds its way into my pack. When I was thinking about which book to feature this month, it jumped to the forefront. I actually had to check to see if I’d used it before and was surprised that I hadn’t.

Produced by the Maine Forest Service, the centennial issue published in 2008 was the 14th edition and it’s been reprinted two times since then.

In previous years, the book was presented in a different format. Two editions sit on my bookshelf, and I need to share with you two things that didn’t find their way into the most recent copy.

From 1981: Foreword–“It is a pleasure to present the eleventh edition of Forest Trees of Maine.

Many changes have occurred in Maine’s forest since 1908, the year the booklet first appeared. Nonetheless, the publication continues to be both popular and useful and thousands have been distributed. Many worn and dog-eared copies have been carried for years by woodsmen, naturalists and other students of Maine’s Great Out-Of-Doors.

We wish the booklet could be made available in much greater quantity, however, budgetary considerations prevent us from doing so. I urge you to use your copy of Forest Trees of Maine with care. If you do, it will give years of service in both field and office.”

Kenneth G. Stratton, Director.

From 1995: One of two poems included. I chose this one because it was one my mother often recited.

Trees

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

~Joyce Kilmer

The most recent edition of Forest Trees of Maine provides a snapshot of the booklets history and information about the changes in the Maine landscape. For instance, in 1908, 75% of the land was forested, whereas in 2008, 89% was such. The state’s population during that one hundred year period had grown by 580,457. With that, the amount of harvested wood had also grown. And here’s an intriguing tidbit–the cost of the Bangor Daily News was $6/year in 1908 and $180/year in 2008.

Two keys are presented, one for summer when leaves are on the trees and the second for winter, when the important features to note are bark and buds.

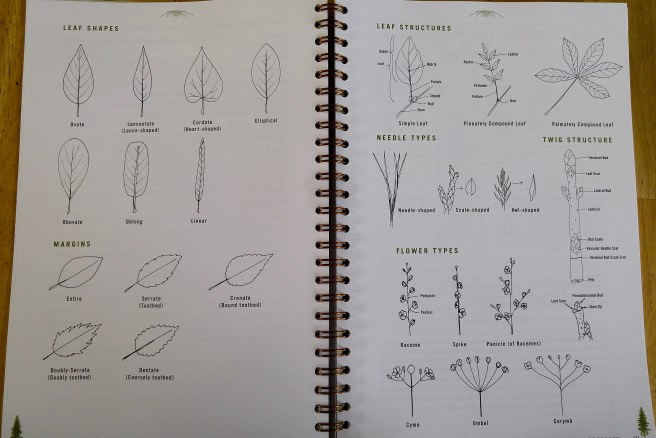

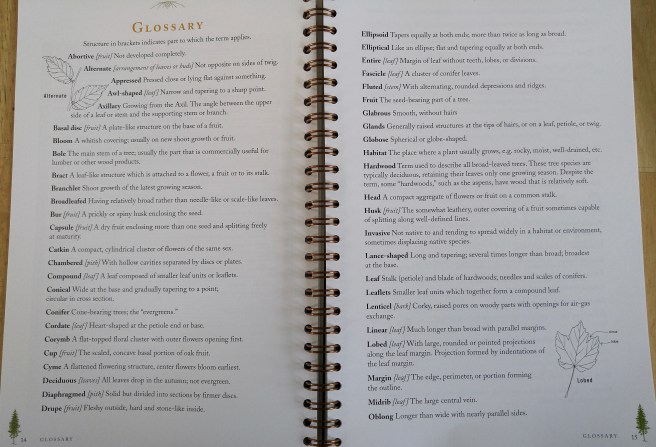

Terms for leaf shapes, margins and structure, twig structure, plus needle types and flower types are illustrated and various terms defined.

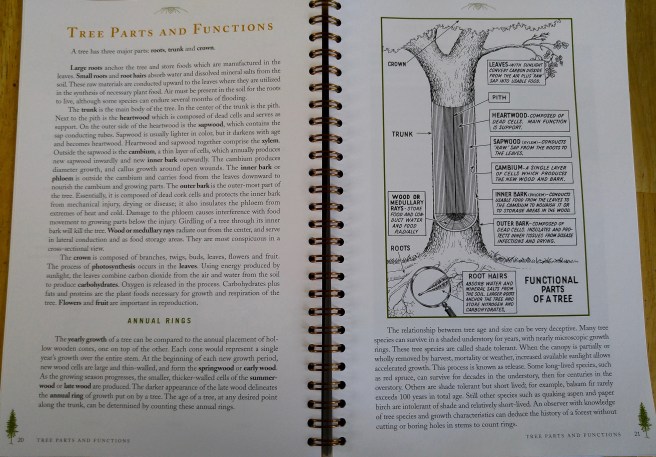

There’s even information on how a tree works because they do–for our well-being and for the benefit of wildlife.

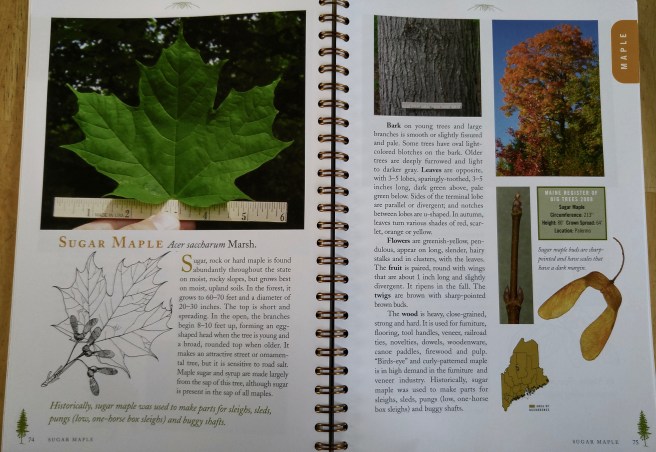

And then the descriptive pages begin. Each layout includes photographs, sketches and lots of information, both historical as in the King’s Arrow Pine, and identifiable as in bark, leaves, cones, wood, etc.

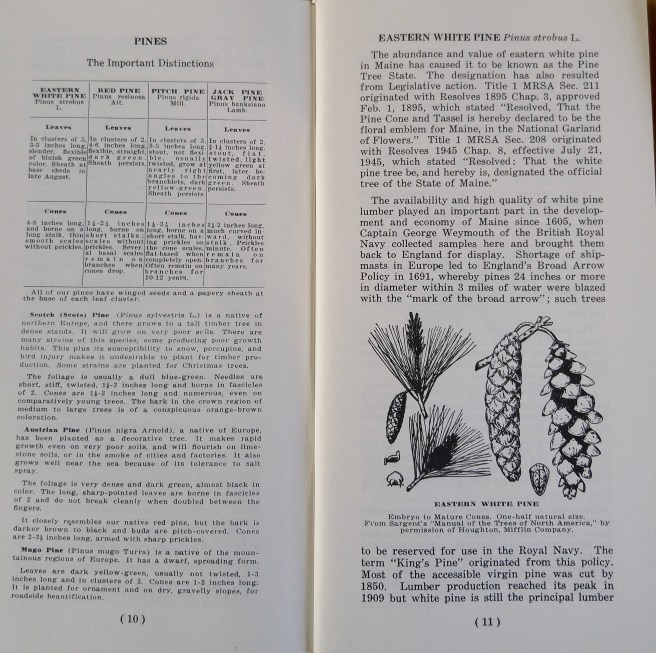

1981

1995

Though some of the information is the same, it’s fun to note the differences from the two earlier publications.

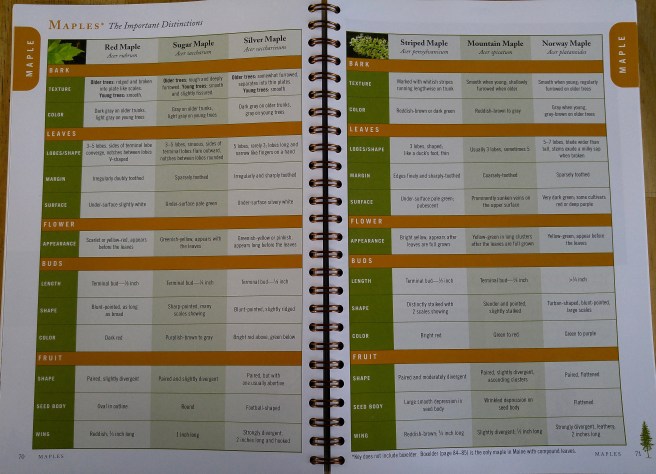

At the beginning of each family, major descriptions are noted in an easy to follow format.

And like the conifers, the broadleaves are portrayed.

Tomorrow, when my friend and I venture off, I’d better remember to pack this booklet. She’s peeked my curiosity about what she wants to ID because I’ve climbed the mountain before and perhaps I missed something. She already has a good eye for trees so I can’t wait to discover what learning she has in mind for us.

This Book of September is for you, Ann Johnson. And it’s available at Bridgton Books or from the forest service: http://www.maineforestservice.gov or forestinfo@maine.gov.

Forest Trees of Maine, Centennial Edition, 2008, published by The Maine Forest Service