Sometimes I need to slow my brain down to figure things out. And other times . . . I need to slow my brain down to figure things out.

That’s exactly what I’ve been trying to do lately. Figure things out. Green things. Evergreen things. That means they add color to the forest floor year round.

Pour a glass of water or a cup of tea and join me as I take a closer look.

At first glance, these green growths appear to be miniature trees. But what I wanted to know was this: is the smaller “tree” on the left directly related to the larger “tree” on the right?

There was only one way to find out and though you aren’t looking at the same two in this photo, the question was recently answered when I began to dig into the ground and a friend lifted up the root system. If you look closely at this photo, the two species we were studying looked less similar than the two in the previous picture.

But indeed they were connected . . . with underground horizontal stems called rhizomes.

Meet Dendrolycopodium obsucurum, aka Flat-Branched Clubmoss or Princess Pine. Some of you know this well as your parents used to create Christmas decorations with it. I caution you–don’t be like your parents. Well, in this case anyway.

Clubmosses are vascular plants like our trees and flowers (but not mosses), thus they conduct water and food through their xylem and phloem. Their reproductive strategy is primitive. See that yellow “candle” or club? That is the strobilus (strobili, plural form) with structures called sporangia (sporangium). Some clubmosses have this structure and others have sporangia formed on the plant’s leaves. More on sporangia later, which means you’ll have to continue reading.

As I get to know these green things better, I’m trying to figure out their idiosyncrasies. And just when I think I know, I get zapped. But . . . the species above is closely related or a variant of the first species I shared. And sometimes they look super similar. The Flat-topped has smaller leaves on the lower part of its branches, but without a loupe, I can’t always spot that. And even with a loupe, my mind gets boggled. Am I seeing what I think I’m seeing. One thing that has helped me is that species, Dendrolycopodium hickeyi, or Hickey’s Tree Clubmoss, prefers drier soil. But really, they could be twins. And truth be known, they do hybridize.

Right now, I’m thinking that Hickey’s leaves, as shown above, are consistently the same length and thicker in presentation as the branches are more rounded than those of the Flat-branched.

On our land, it grows abundantly along Central Maine Power’s Right-Of-Way and like Flat-branched has underground rhizomes. In fact, this afternoon I had a vision of a bedspread from my youth that I turned into roads and drove little rubber cars and trucks along when I played “Town.” I could easily have driven my little cars from one “tree” to the next and followed the rhizomes as if they were invisible roads.

Cool sights reveal themselves when I do slow down like this and I thought that CMP had killed the Sundews that grow under the powerlines when they sprayed herbicides along the route several years ago. I’d given up on being the guardian of such special plants, and was delighted to discover their dried up flowering structures today and locate the wee carnivorous leaves below. Yahoo! High five for Sundews!

Where Flat-branched and Hickey’s have underground rhizomes, this particular member of the club features horizontal stems that are above ground runners.

And while the previous two were tree-like in structure, this one reminded me of a cactus.

Furthermore, I got all excited because I thought I’d discovered a species considered threatened in Maine. I talked myself into it being Huperzia selago or Fir-Moss. It looked so much like the black and white sketch in my field guide.

Until I realized the Fir-Moss has a sporangia-bearing region in the upper stem. And my species has strobili located at the tips of long slender stalks. And there is no mention of those transparent hairs in the description of the Fir-Moss (after all, it’s not Fur-Moss), but Running Ground-Pine or Staghorn Clubmoss does have this feature. Thus, this is Lycopodium clavatum.

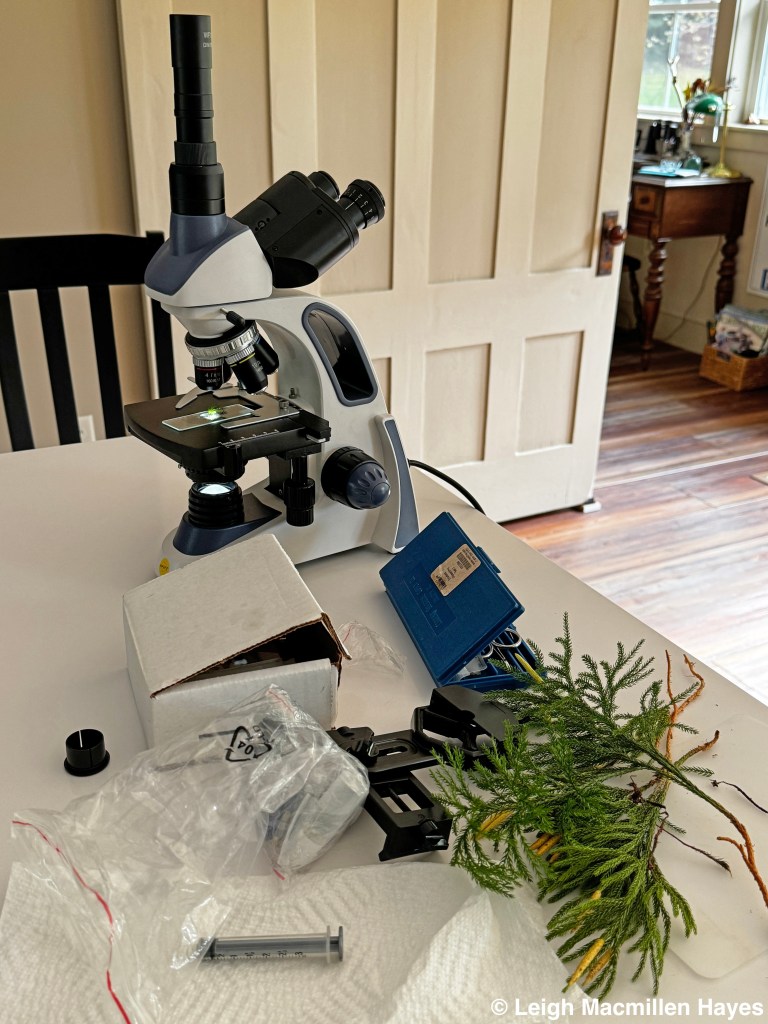

Back at home, it was time to set up the mini-lab and take a closer look. I try not to collect too much; in Ferns & Allies of the North Woods, Joe Walewski suggests we “consider the 1-in-10 rule: collect no more than one for every ten you see.”

The microscope has opened a fascinating world to me–as if it weren’t already fascinating enough. And see the pattern of cell structures–an art form all its own.

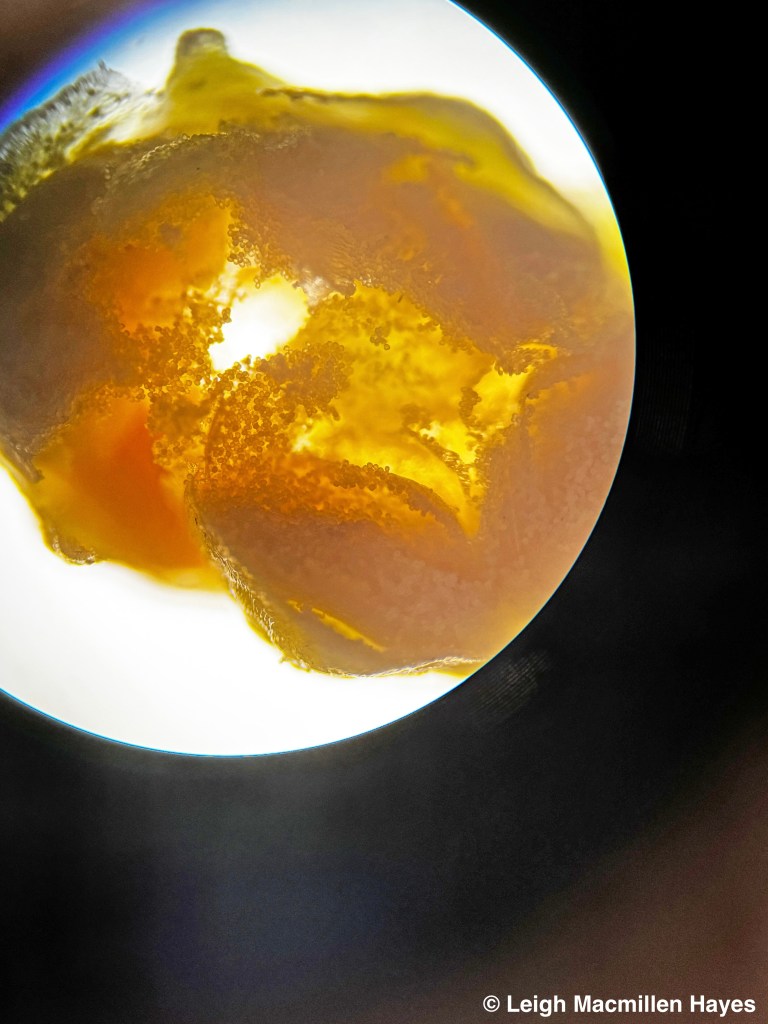

And then there was the strobili that covered the sporangia. That word sounds like dessert and this look at the structure made me think it could be some decadent butterscotch offering.

I cut a cross-section and was surprised to see the hollow center.

All those minute spores. Actually, I accidentally nudged a few as I walked in the woods this weekend, and had the honor of watching the “dust cloud” of spores being released.

One family member that doesn’t live in our woods, but is located close by is this, Diphosiastrum digitatum or Fan Creeping-Cedar, so named for its resemblance to cedars.

This specimen had followed me home a few weeks ago, and when I pulled it out of my now warped field guide, for so damp were the pieces that I stuck in there, it had dried into a flattened form of its former self.

I stuck a piece under the microscope and again was floored by the thickness and cell structure.

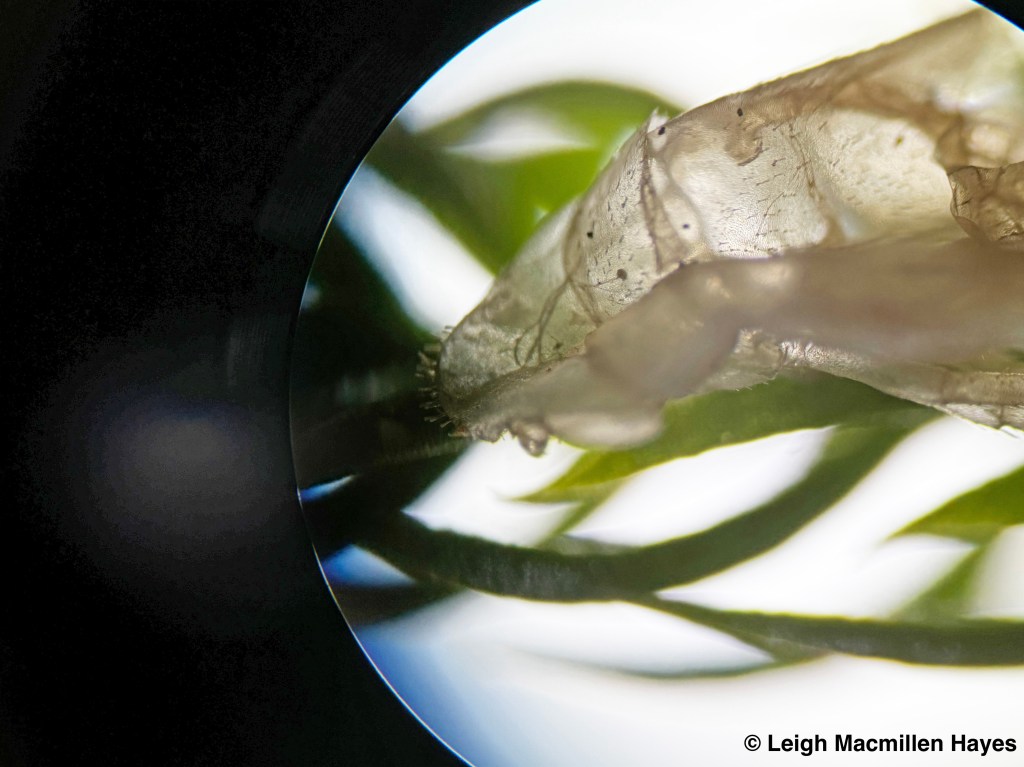

And then I had a surprise. A hitchhiker! Do you see the long legs?

Here’s another look. I don’t know who this was, but I do know that it was minute in size and it appeared to be a shed skin after the insect had molted.

Suddenly I was eager to find more. And so I checked out a piece of the Flat-branched . . . and wasn’t disappointed.

Here it is again. The second critter that is. Or was. And now I can’t wait until next spring and summer to find out what tiny creatures use these structures as places to molt. And maybe feed. The mouth structure, if that’s what it is on this one, appears to be almost fan-like and kind of reminds me of that on a slug.

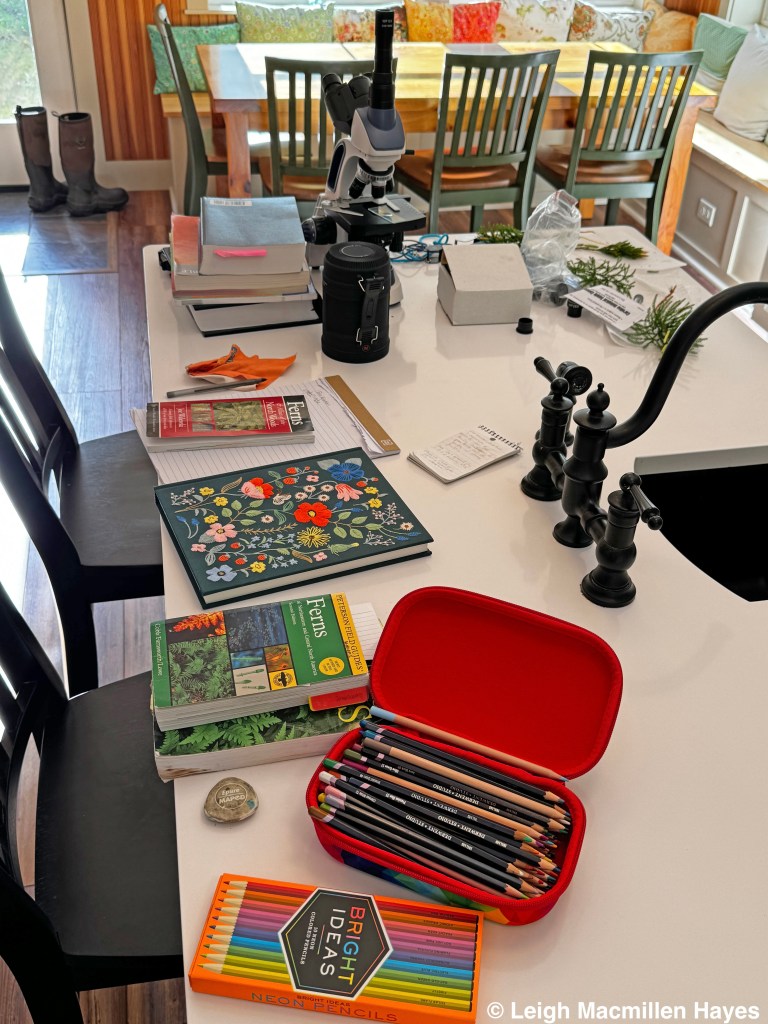

The home lab grew into an art room as the hours passed.

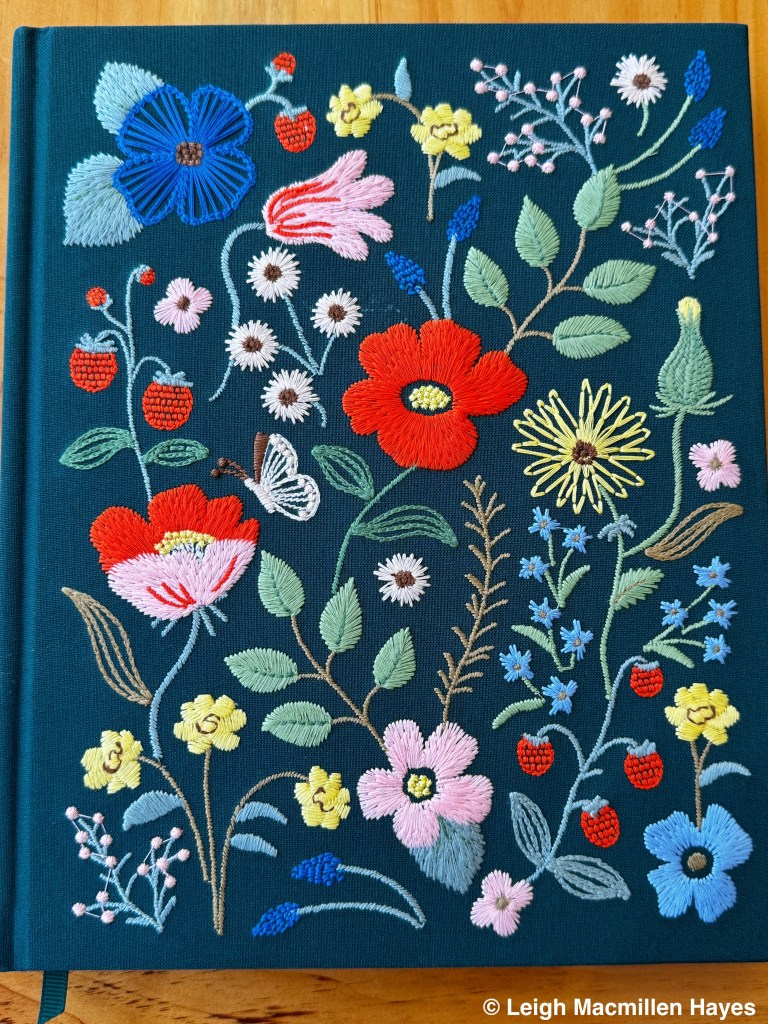

Recently my sister gifted me a sketch book and it begged to be opened. After running my fingers over the cover first, of course.

I have the perfect bookmark to mark the pages, created for me this past year by one of our first playmates.

Getting to know a species better through close observation and by sketching is one of my favorite pastimes. And I’m so glad I slowed my brain down, especially when it came to hickeyi on the left and obscurum on the right. The differences seem so obvious with these two examples, but step out the door and I suspect you may be thrown off course as well.

When is a moss not a moss? When it’s a Clubmoss, which is actually an ally or relative of ferns. And horsetails. All are non-flowering vascular plants.

Before you depart, dear reader, please remember that these are ancient plants that take a long time to germinate as most need a symbiotic fungi to provide nutrition to the gametophyte stage (think gamete, eggs, and sperm). They may lie dormant underground for up to seven years and then take up to fifteen years to develop reproductive structures. In the great coal swamps of the Carboniferous period, they reached heights of possibly 100 feet, something I have a difficult time comprehending when I look at their small forms in our woods. Their growth is slow and they deserve our respect.

And now I can’t wait to meet some others and get to know them as well. I spotted One-Cone Ground-Pine or Lycopodium lagopus on a hike the other day and kick myself for not taking its photograph. All in their own time. I’ve made a start and hope you will do the same.