What is a wetland? Basically, it is wet land! But more specifically, wetlands are often those transition zones between dry land and deep water.

There are four basic types of wetlands, which can be broken into even more types, but let’s stick with the four: marsh, swamp, bog, and fen.

Marshes are typically located along shores of rivers and streams, and even the coastline. Plus they can be found in the shallow water of ponds and lakes. Cattails, Arrowhead and other soft-stemmed emergent plants grow in these areas.

Swamps are found along rivers, streams, and lakes where mainly woody-stemmed plants such as shrubs and trees, like this Tamarack, grow.

Bogs are found in our northern climate and often are deep depressions that have no drainage. They are covered with a surface carpet of sphagnum moss and insect-eating plants like the Pitcher Plant and Sundews.

Native Cranberries also flourish in the stagnant and acidic water of a bog.

Like bogs, Fens are found in northern climes, but the water is slow-moving, and does have some drainage. Layers of peat (sphagnum moss) and sedges and grasses and low shrubs like Leatherleaf may grow in these areas. The carnivorous plants like them as well.

But it’s not just the flora that makes a wetland so special. These places provide habitat for a wide range of insects and animals and birds as well. In fact, they act as nurseries, or places where any of the critters might raise young.

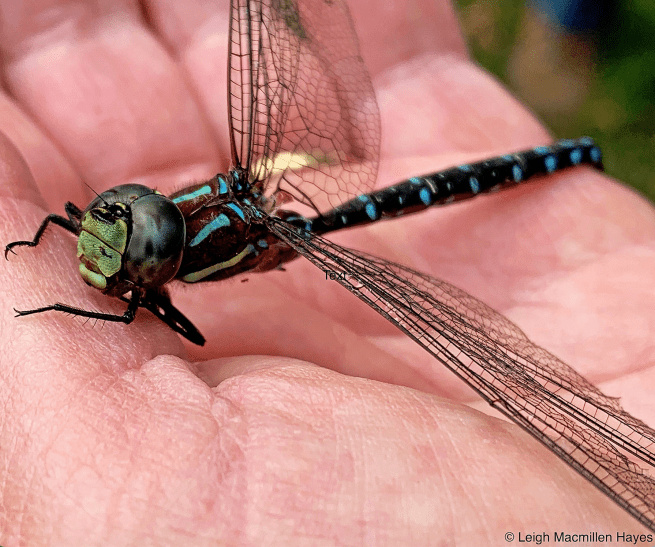

And as soon as the sun warms the air in the spring, friends and I scour the wetlands in hopes of discovering who is emerging on any particular day. One of my favorites to watch is dragonfly emergence (in case you are new to this blog and didn’t already know that. You can learn more here: Developing Dragonfly Eyes, but really, type “dragonfly” into the search button of this blog and a bunch of dragonfly related posts will pop up–all worth a read, I promise you.)

And like other insects, once emerged and a few days old, canoodling commences and dragonflies such as these Belted Whiteface Skimmers find each other and a presumably private place to mate. Private, that is, until I show up!

Eggs are laid in a variety of ways and places depending upon the species and this is a female Eastern Pondhawk taking a break upon a lily pad.

And here is a Forktail Damselfly laying eggs upon vegetation.

Frogs are also a highlight of a wetland, whether they are hiding in the shade on a hot summer day like this Bullfrog …

Or pausing briefly in the sun, such as this Pickerel Frog chose to do. Actually, it wasn’t so much basking as trying to remain hidden from my sight by not moving until I passed.

Those who do love to bask, (frogs do this as well) are the Painted Turtles, and the more surface area that is exposed to the sun’s beams, the better. Sometimes I’m surprised when I do capture a photo such as this one, for they are quick to sense my presence or hear me coming, and quickly slip into the water. But if you wait a few minutes, sometimes they’ll reemerge.

And there are Northern Watersnakes always on the prowl, using their tongues to make sense of their surroundings.

Mammals also use wetlands for forage for food and build homes and one of my favorites is the American Beaver, who knows the value of a wetland, and can create one in a short time by building a dam. Beavers build dams to created a deeper pond through which to navigate, for they are better at swimming than walking. They may alter the wetland to suit their needs for a few years, but then move on and let the dam breach and then a new type of wetland emerges and more critters move in and take advantage of what it has to offer.

That all said, it wasn’t until I spent more time with the animal pictured above that I realized it was actually a Muskrat–look at that thick, rounded tail, unlike the flat paddle of a Beaver’s.

And birds! Oh my. Mergansers . . .

And momma Wood Duck and her offspring . . .

and Papa Woodduck . . .

And Great Blue Herons always on the prowl for fish or amphibians know the value of the wetland as a food pantry.

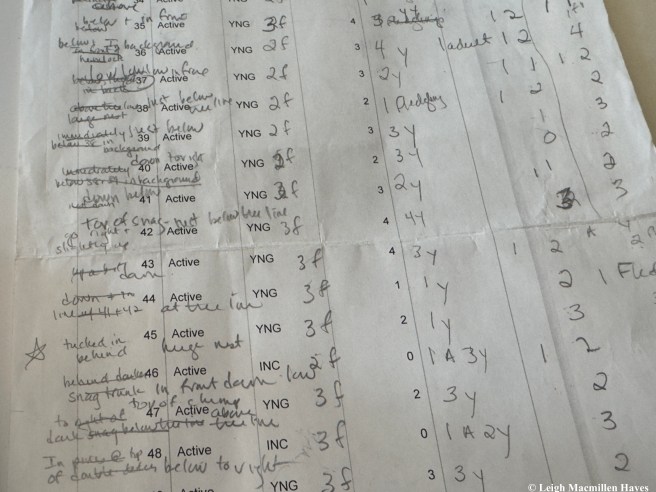

So, this spring and summer and fall, I’ve been following My Guy and our friend, Bruce, beside and into and sometimes, thanks to Bruce’s drone, over a variety of wetlands.

Bruce is an early riser (understatement), and occasionally I’ll meet him at a predetermined location as we did this past weekend–before the sun has risen. Though the thought of staying in dreamland for another hour or so is enticing, I never regret the decision because we get to view the world before it officially wakes up.

And with his drone we explore these areas we cannot easily access. This is one My Guy and I walked all the way around a few weeks ago without ever spying, though we knew it was there. But Bruce and I bushwhacked through a forest of White Pine Saplings and mature trees and reached the edge before he launched his bird and we were offered a glimpse of this most beautiful wetland with pockets of water connected by meandering rivulets.

The stream turned to forest for the trees told more of the story, as they closed in and I recalled that it wasn’t far from that spot that My Guy and I walked through a damp area where Royal Ferns grew and we found one teeny tiny mushroom fruiting on a hot summer day.

The mushroom was the little Orange Peel Fungus, and its name seemed so obvious. And the soil moist despite the severe drought.

Another day we began our exploration in the afternoon beside a small pond.

And the Droney-bird picked up on the wetland to the south.

But that day what struck us as being more important was that it also took a clear picture of a sandbar in the water.

And as Bruce navigated it closer to the watery surface, we could see clear to the bottom. Mind you, it’s not a deep lake, but this is the water of Maine. Clean and clear.

And we celebrate wetlands for the critical role they play in maintaining the health of the environment.

When I think about their ability to store and filter water and act as a natural sponge, absorbing and retaining large amounts of water during the heavy rainfalls of spring, and removing pollutants before they enter streams, and rivers, and lakes, it all seems so obvious that they should do this when you have a bird’s eye view.

So here’s the curious thing about this wetland. It is located beside a local dump. And the more I think about that, the more I question those who created the dump, but give thanks for the unwavering workhorse that this wetland is in the ecosystem.

It was on the rise above this particular wetland, in a very sandy spot covered with Reindeer Lichen, that Bruce and I made a discovery. Well, he discovered it first and asked for an opinion. I’m full of those and so I met him and we took a look.

The discovery was a plant new to us both. Sand Jointweed or Polygonum articulatum. As you can see, the flowers are astonishing in their pink and white display.

It was the stems that I found equally fascinating. At the base of the flower stalks there are sheathing bracts, giving it a jointed or segmented appearance. We didn’t see any leaves, but perhaps we need to look again. I think we were just amazed to have discovered a plant neither of us recalled meeting before. Often though, that means we’ll meet it again soon.

The small snippet followed me home, and today I looked at the flowers under the microscope and I was astonished to realize that they look rather like a map of a wetland.

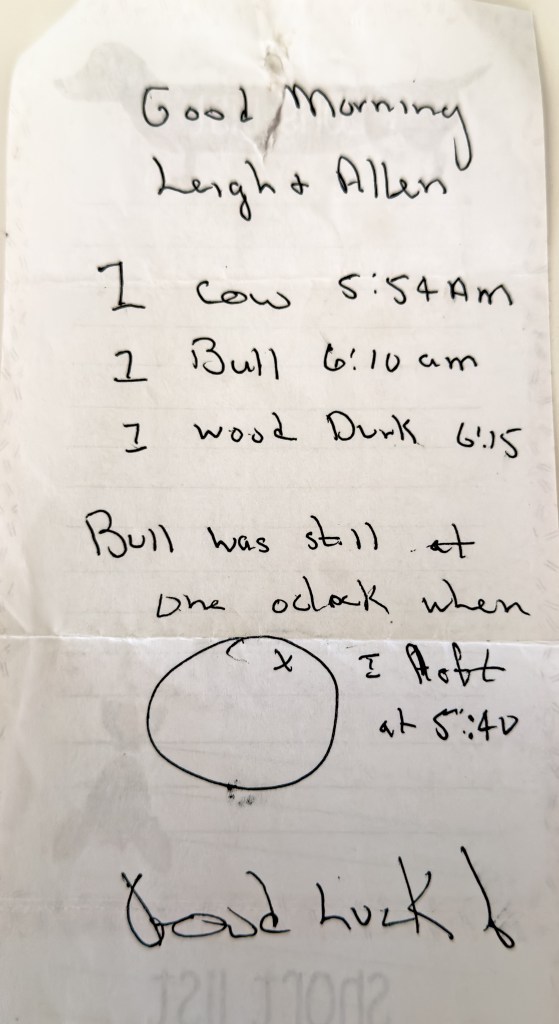

I don’t jump at the invite every time it arrives for an early morning mission to explore a wetland, and one day really regretted it because when My Guy and I finally got to the location, we found a note with Bruce’s observations. We scanned the area with our eyes for about an hour before deciding that we were too late.

But . . . we promised ourselves that we’d pack a picnic supper and try again.

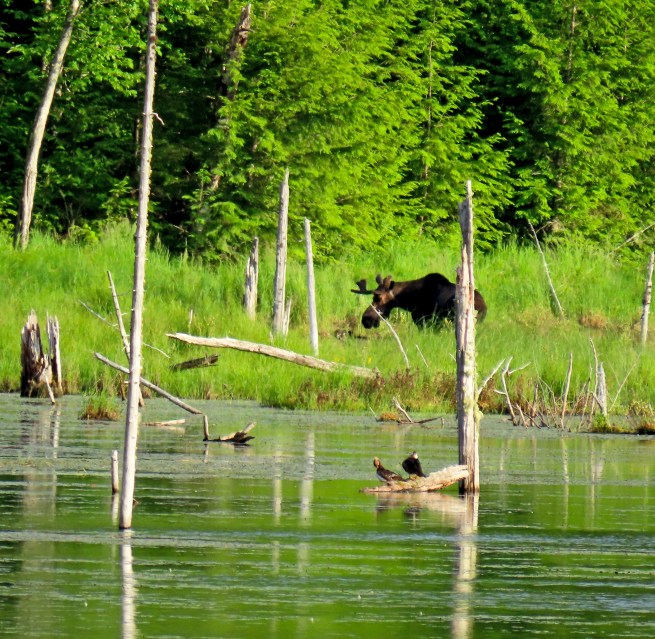

First we spotted one Bull Moose.

And then a second, and had a difficult time deciding that we should head home.

Did you know that 25% of Maine’s land area is wetlands? That’s four times the wetland area of the other New England states combined. The natural buffers they provide sustain the deep clear water we appreciate, and take for granted.

The margins or places where the land and water come together are bridges between two worlds. As many as 90% of all living things in our waters are found in these wetlands, no matter what form they take. I guess that’s why I love exploring them so often, because there’s always something to see. And another lesson to learn.

I leave you with this, a watercolor Bruce’s wife Eileen sent me recently. It was inspired by one of our local wetlands.

Some may see wetlands as dark and shadowy areas, mosquito hatcheries, with an abundance of leeches mixed into the scene, but the rest of us know their true value and I give thanks for living in this place where it’s so easy to go Bogging in Maine. And to share it with others. Thank you MG, BB, and EJB!