We live on the edge. The edge of a small town in western Maine. The edge of a neighbor’s field. The edge of a vast forest.

Our property only encompasses six acres, but it’s six acres that I love to explore and it’s been my outdoor classroom for a long time.

And so today, I invite you along to take a look; if you are a regular, you may have already met the friends I’m about to introduce, but their actions keep me on my toes, much like the deer who crisscross our yard on a regular basis.

Though the acorn crop was abundant in our area, the deer make several trips day and night to consume sunflower seeds and corn and they’ve worn a path (deer run) making it easier to travel. They don’t always follow it, as you can see, but do so enough that it’s much like my snowshoe trails.

The yard is full of tracks, for besides the deer, there are gray and red squirrels who also frequent the feeders, an occasional red fox that I’ve yet to see this winter, and our neighbors’ dogs and cats. Everyone has a place at this table.

Of course, the deer run does lead to another species they love to munch on, the needles of a Balsam Fir. They frequently pause here before climbing over the stone wall into our wood lot.

And so I paused too. And discovered yet another cache and midden created by one of our local Red Squirrels. I’m in awe because until yesterday, I wasn’t aware of this one and I can see it from the desk where I’m writing right now. And to top it off, yesterday was the first day since I filled the feeders at the beginning of December that I saw a Red Squirrel chasing the Gray Squirrels away.

I, too, climbed over the wall and look who I met. Always on alert and often either skittering along the ground or a stone wall, or chastising me from its branch of choice, Red doesn’t realize that I’m a fan.

Next, I ventured over to the old cow path, bordered as it is by two walls, and checked on the cache and midden situation that’s become so familiar to me.

The cache or storage pantry of pine cones is located under the mound of snow the black arrow points toward. At last measurement as recordered in The Forever Student, Naturally, the pile was a foot high. As you can see if you look closely at the tops of the stones behind the snow-covered pile, you’ll spy several middens. So my question is this and I’ll have to wait until the snow melts to answer it: Are all of the cones the squirrel is consuming (well, seeds actually, for the midden is the pile of discarded scales that protect the seeds, plus the cob or core left at the end) coming from under the rocks, where I’m sure there was more storage space, or the bottom of the pile, because Red Squirrels do tunnel? I can’t wait to realize the answer in another month or so.

The pine tree beside the cache also provides a grand dining spot.

About an inch of snow fell overnight, so when I went into the woods this morning, I found fresh Red Squirrel prints, with the straddle or track width being the typical three inches. It was a bit nippy with the wind chill, so I didn’t get the card placed exactly as it should have been, but you get the idea. Its big feet in front are actually this hopper/leaper’s hind feet.

Okay, so I did risk the freeze for a minute because I spotted the set of four prints behind the first set I’d photographed and realized not only how close together the four were, but also the length of the leap from one spot to the next: My mitten and wrist holder are 19.5 inches in length and they didn’t cover the length of this motion–perhaps an attempt to quickly reach safety in the other wall or up a tree.

That action was on the eastern end of the path, but there’s more to see as I head west.

A few days ago, and probably because the night temperatures were more moderate, a family of rascals crossed from the other side of the wall and onto the path. By the baby fingers of the front foot, I know they were Raccoons.

As waddlers, Raccoons have their own pattern that is easy to recognize once you get it into your head. They don’t travel this way all the time, but most often I find their prints, with a front foot (baby hand) of one side and hind foot (a bit longer print) of the other side juxtaposed on opposite diagonals. If you look at the black lines I placed before each set of two prints I hope you’ll see what I mean. And notice the keys. It’s all I had in my pocket that day and I wanted something for perspective. I really didn’t expect to find the raccoon tracks.

I went back home and grabbed a tracking card to set on the ground. If you’ll look closely, you’ll note that it’s more than one animal, but all the same family. I followed them across the wood lot, over another stone wall, and into the field where they split up into four individuals before heading off in to the neighbor’s woods on the far side.

Back to the cow path I did return and this time it was a scene just off the path that drew my attention. Our Pileated Woodpecker has been active as evidenced by all the wood chips on the ground. That means one thing to me. Time to look for scat.

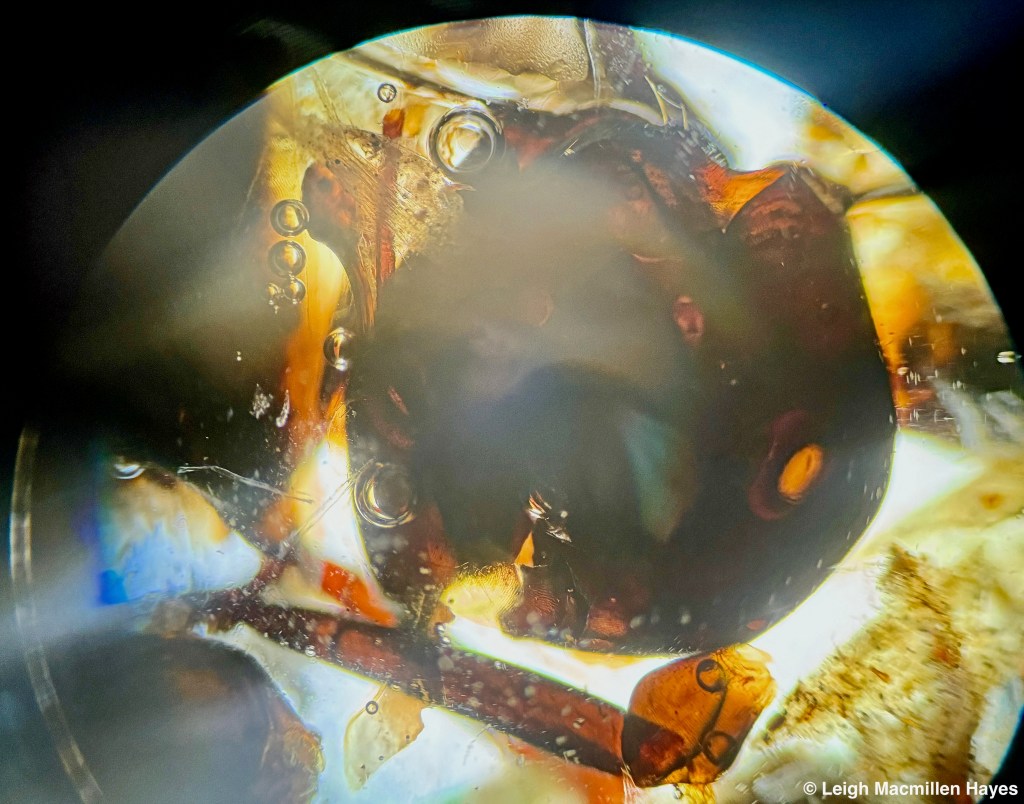

And I wasn’t disappointed. Check out that cornucopia stuffed chock full with insect body parts that the bird couldn’t digest.

Finding this is always like opening a Christmas present. The thrill never ends. But, curious spot here. Seeds. Staghorn Sumac seeds.

And on the pine tree and at its base, I found more of the Staghorn Sumac in bird droppings, a completely different form from the Carpenter Ant droppings.

Both followed me home! The Carpenter Ant scat is very fragile.

The sumac, being fleshier, held together better. Under the microscope I noted that there were some ant body parts mixed in with the sumac.

Here’s a closer look at one of the legs of a Carpenter Ant–notice the long “thorny” thing, which is the tibial spur located at the base of the tibia.

And an exoskeleton plus another leg. With lots of wood fiber in the mix. Lots of nutrients and fibers mean scat findings for me.

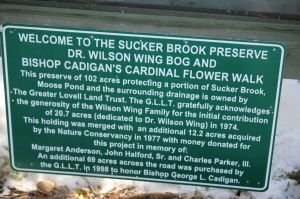

A power line bisects our property and I have a love/hate relationship with it. I do love that it looks like we could walk north to Mount Washington. But my destination was to the trees on the western (left-hand side), where we own at least one more acre enclosed by stone walls.

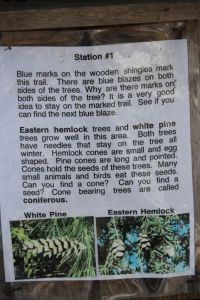

About half of that acreage is a combo of hemlocks and firs fighting for sun. In the end, the hemlocks will rule the world, but the firs are trying to compete.

It is here that I discovered Snowshoe Hare tracks and my heart smiled again. There’s not much on this portion of our land for the hares to dine upon, such is the landscape when the trees block undergrowth. But on either side of the walls, there’s plenty available to them in areas that have seen timber cuts within the last twenty years.

Here’s the thing about hare prints–as hoppers, the smaller front feet land first and often, but not always, on a diagonal. The much larger hind feet swing past where the front feet had been as the mammal moves forward, and thus appear to land in front when you look at the overall pattern. And my favorite part of this set of four footprints: the overall shape, which to me looks like a snow lobster with the front feet forming the tail and hind feet the claws. Do you see it?

This neighborhood on the other side of the power line also supports a Red Squirrel who in true squirrel tradition travels this way and that.

And like its relative on the other side, it took time to cache a bunch of cones and now feasts upon its supply.

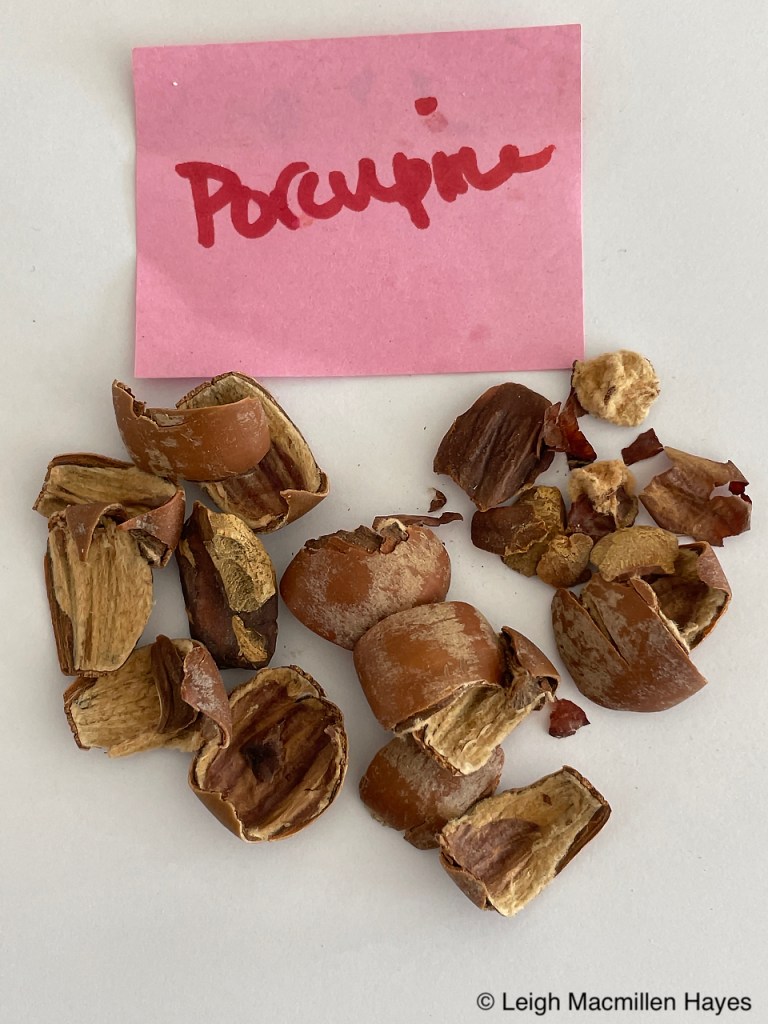

And leaves its garbage for nature to recycle. Notice how the middens are often located on high spots such as the rocks along the wall–the better to be in a spot where you can see who or what might be approaching. Even those on the ground below trees mean that the squirrel probably did most of its dining from a branch above, and then let the trash fall.

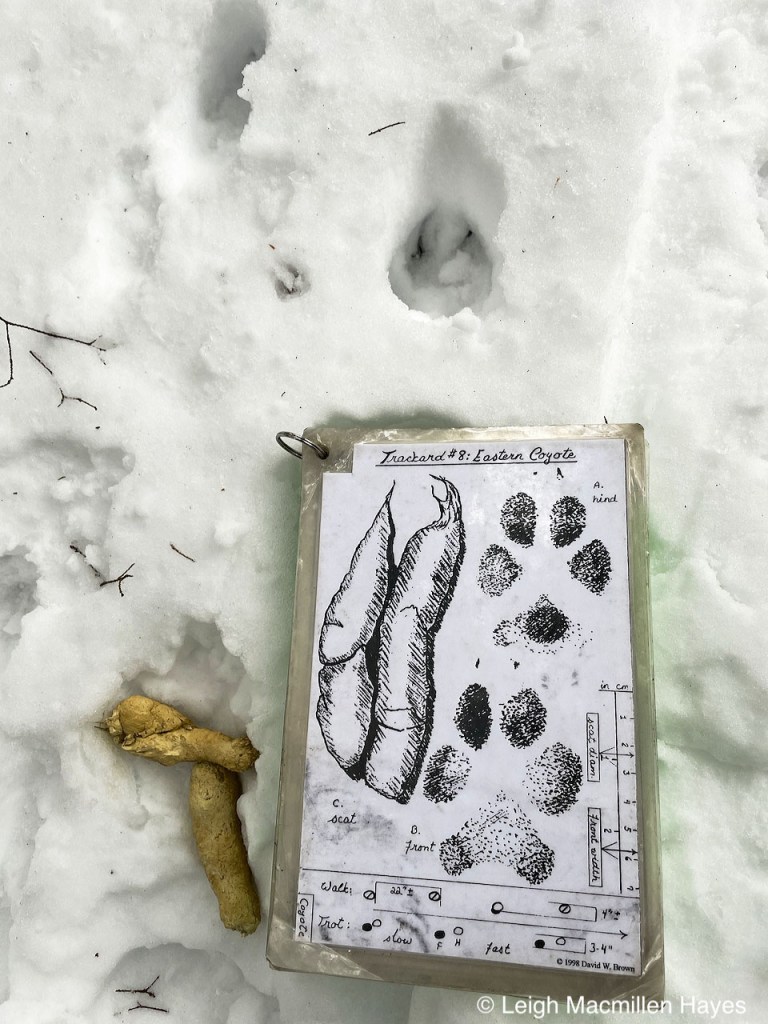

What could a squirrel possibly fear in these woods? Besides coyotes and foxes and bobcats, oh my, think Fisher such as the one that left these tracks in the squirrel’s territory. As far as I could tell, the Fisher (and it’s not a cat, it’s a member of the weasel family) was only passing through, probably on its way to hunt down the hare. Though a squirrel would make a fine meal, as well.

Heading back across the power line, cases stood out on the White Pine saplings at the start of the cow path. The cases consisted of clusters of needles bound together. This is the work of the larval form of a Pine Tube Moth, Argyrotaenia pinatubana. What typically happens is that the caterpillar uses between ten and twenty needles to form a tube or hollow tunnel.

The caterpillars move up and down their silk-lined tunnels to feed on needles at the tip until they are ready to overwinter.

The moth will emerge in April, when I’ll need to pay attention again. Two generations occur each year and those that overwinter are the second generation.

Walking home via a different path in our woods, I spot deer beds. At least a half dozen spread out under the pines and hemlocks, the spot where the evergreens keep heavy amounts of snow from reaching the forest floor, thus making it easier for the animals to move.

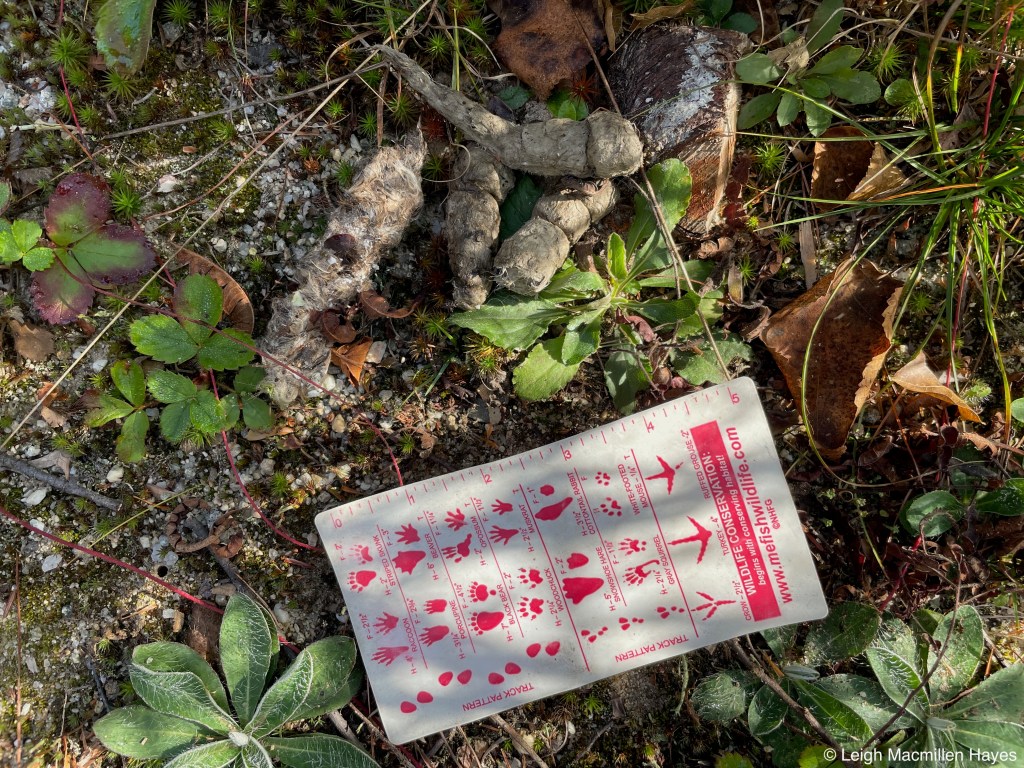

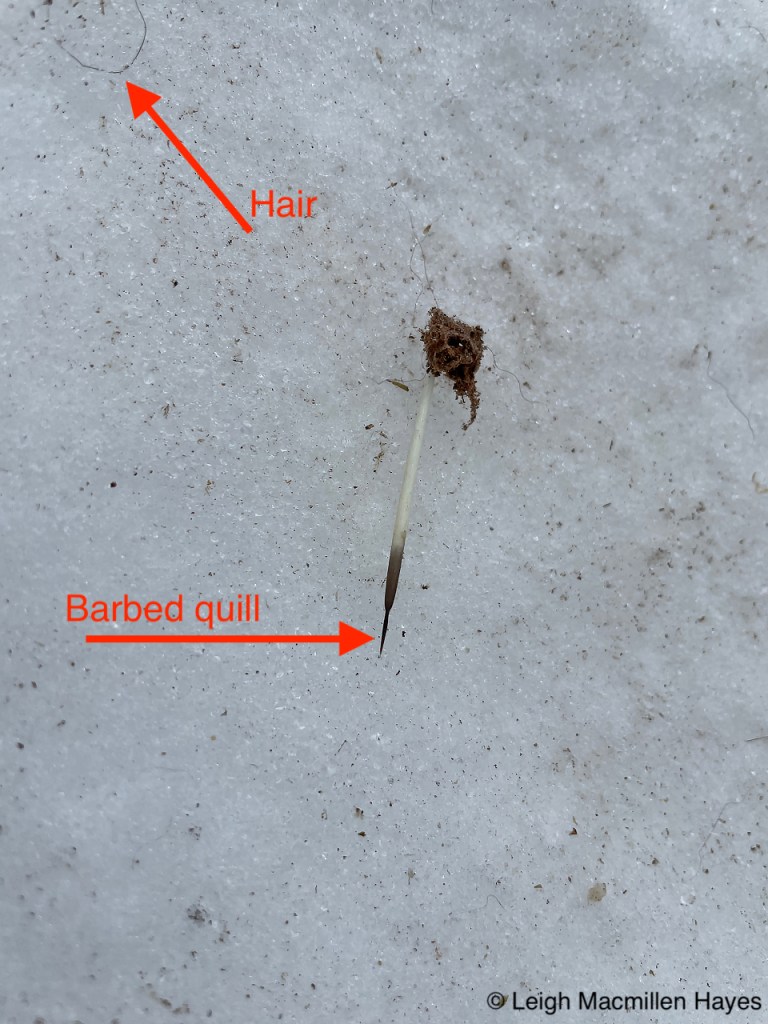

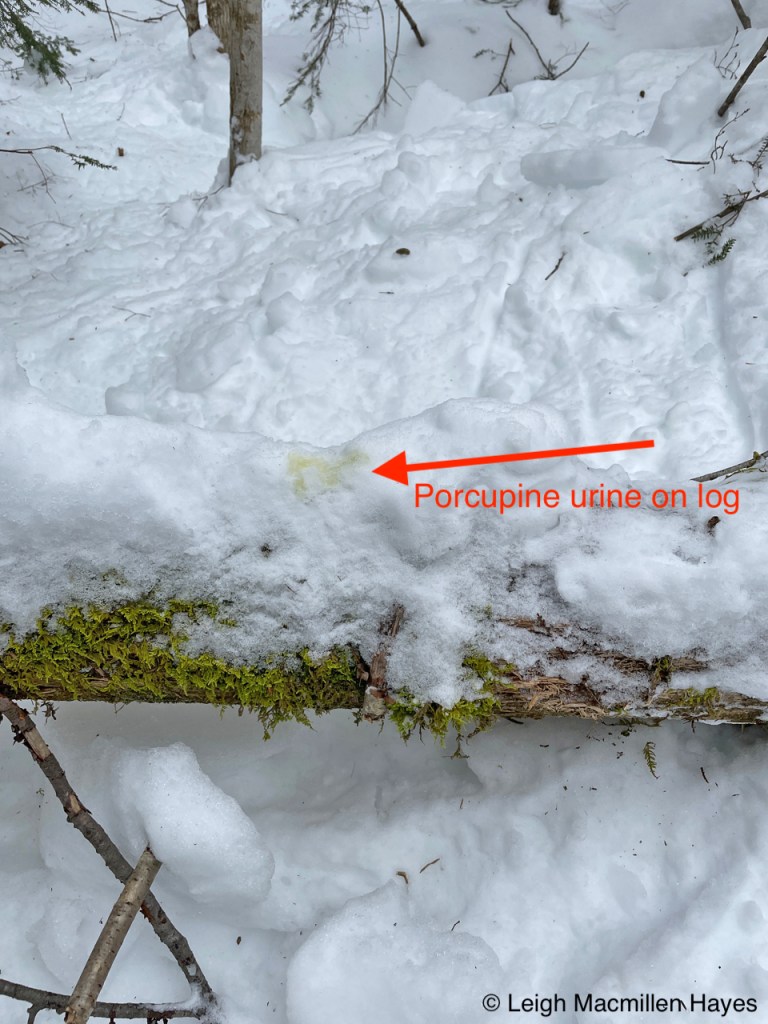

Finally back home, there’s one more member of our family to mention–a porcupine. This may be my friend Bandit, but I haven’t actually seen him in a while so I can’t be certain.

The porcupine did check out a tiny hole under the barn, but we don’t think it actually stayed there. Will it return. Probably, as the barn has long hosted this species; along with other small critters.

That’s a lot for now and at last I’m done counting the stock for our winter inventory. There’s more out there, but this is certainly enough to make me realize that they don’t live in our woods, but rather, we humbly reside in theirs.