Today’s adventure found us exploring another “new-to-us” trail system, this one located beside the Swift River in Albany, New Hampshire.

The Albany Town Forest is protected with a conservation easement by Upper Saco Valley Land Trust. It seemed apropos that we should choose such a trail for today marked the last day with the land trust for their Outreach and Office Manager, Trisha Beringer. Trish is moving on to new horizons, for which I commend her, but at the same time, I’ll miss bouncing collaborative ideas off of her, searching for anacondas as we paddle local rivers, and giggling till we almost wet our pants as we try to strap kayaks onto our vehicles. (Wait, what? An anaconda? In Maine or New Hampshire? Well, when you’re out in the wilds with Trish, you never know what to expect. We did once encounter three otters.)

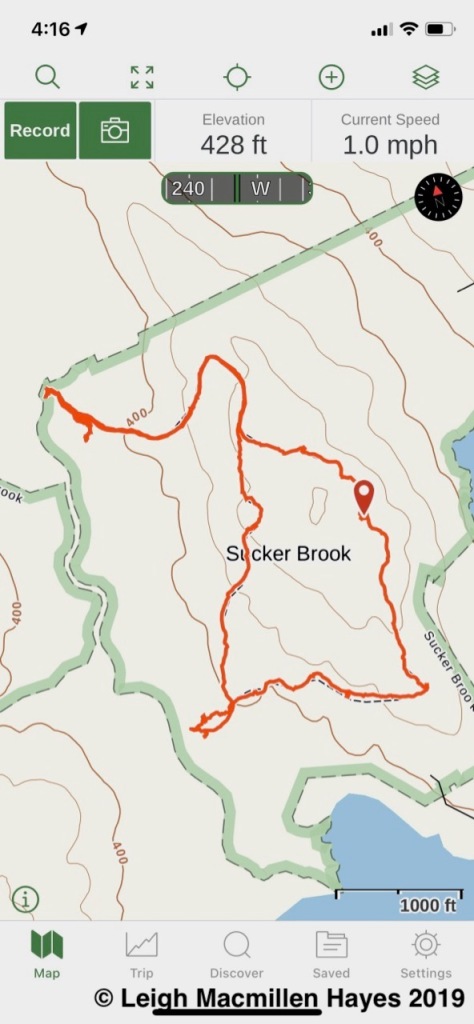

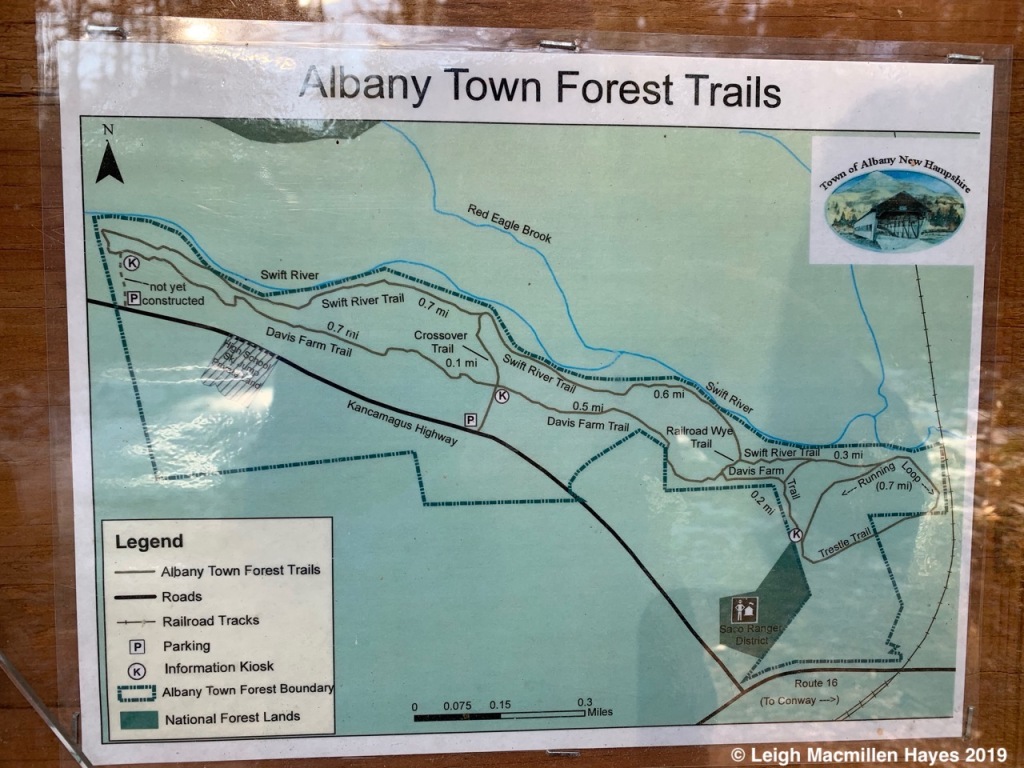

The route my guy and I chose for the day was posted at the kiosk located on the Kancamagus Highway, aka the Kanc. Our plan: follow the outermost trails in a counterclockwise pattern–just cuze we felt like going against the grain.

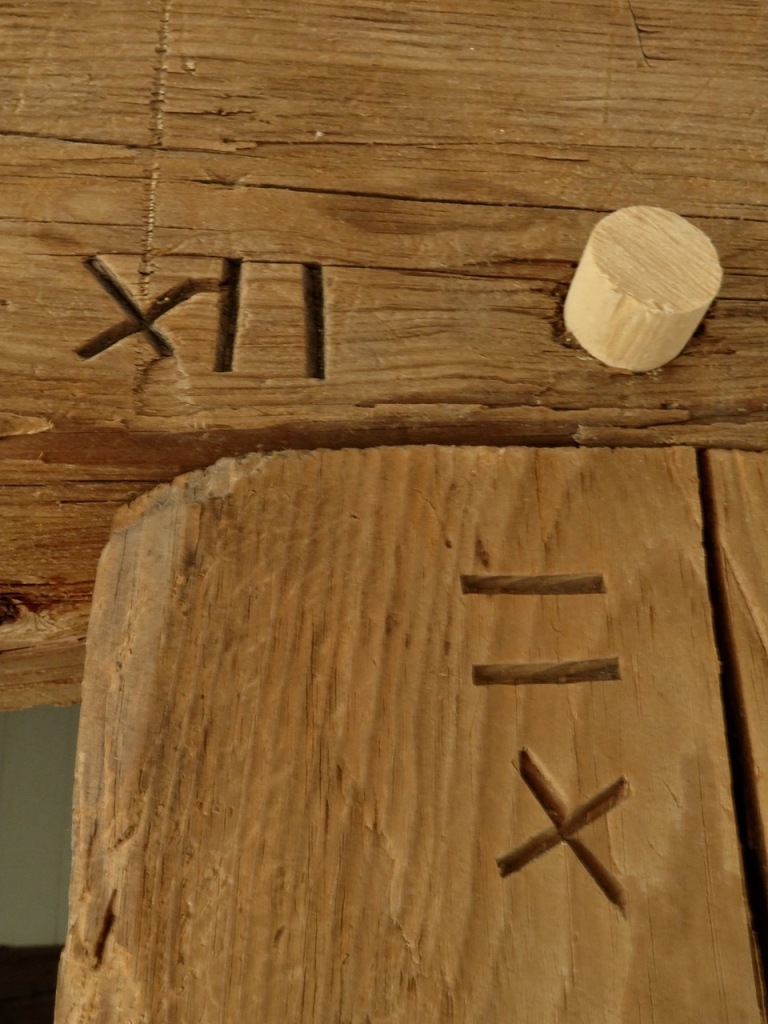

But first, there were other things to appreciate including a tiny beetle on the wood of the kiosk. It looked like a shield bug, but was ladybug in size and had an interesting blue coloration. If you look to the insect’s right, you may note more of the blue hue. I suspect this curious insect somehow met a bit of chalk or paint.

,

A few more feet and we found apples decorating the forest floor. Though some had nibble marks, these appeared untouched. Perhaps the critters kept them in cold storage with thoughts that on Thursday they’ll make a delightful addition to a turkey dinner.

A small bird nest also decorated the forest floor, though we suspected it had fallen from the limbs above.

It seemed ornaments were everywhere and we found this Polyphemus Moth Cocoon dangling from a shrub’s branch. This is a member of the giant silk moth family who draw their collective name from the fine silk they use to spin their cocoons. The cocoons serve as protection for the pupal stage in their life cycle. I don’t know about you, but every little thing in nature astonishes me. How do all Polyphemus moths know to spin this shape?

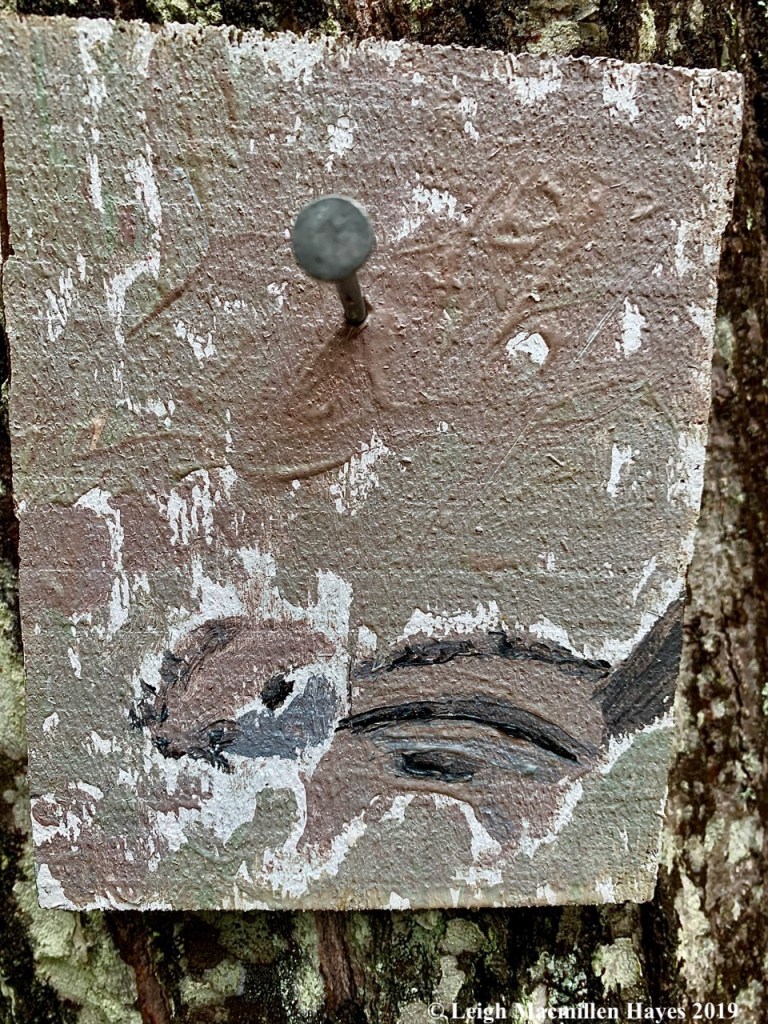

Maybe the wise old chipmunk knows for he seems to be the keeper of the forest this year. And there are plenty of acorns on the ground to add to his pantry.

Through the forest we walked, enjoying the grade of the trail and feel of the place.

And then the community changed and we found ourselves moving beside bent over coneflowers, gum-drop shaped in their winter form. And do you see the baseline for a spider’s web?

Next door was a goldenrod bunch gall created by a midge. Looking like a mass of tiny leaves, it’s also known as a rosette gall for the shape at the top of the stem. In both cases, it’s amazing that insects can change a plant’s growth pattern so dramatically.

As the natural community changed, so did the material world and suddenly we heard the buzz and saw a jet zoom by.

We were fooled momentarily for it circled round and round, came in low for an almost landing as we approached and then took off again. We’d stumbled upon the site of the Mount Washington Valley Radio Control Club.

Airplanes and helicopters weren’t the only ones waiting to lift off into flight. Part of the field was filled milkweed pods, their parachute-equipped seeds waiting for the control tower to give the signal so they could fly.

And where there are milkweed pods, there are also milkweed flowers in their winter form, for such did the structures look with petals of five or six creating the display.

The Davis Farm trail passed by the milkweeds and cut through the fields and I had visions not only of my guy in front of me, but of summer visitors. I’m thinking butterflies, dragonflies, pollinators, oh my.

For now, the fields are dormant, save for a few lone pumpkins adding to the autumn landscape.

And the Moat Mountains providing the backdrop.

By the far edge of the field, hardly cuddly thistles added more texture to the scene.

Staghorn Sumac’s offering was its raspberry color.

At the edge of the field we reached the Swift River and train trestle that crosses it as memories of rides on the Valley Train of the Conway Scenic Railroad when our “boys” were young flashed through our shared memory.

Meeting the river meant that our journey along the Davis Farm Trail had morphed into a western path beside the river and we welcomed its voice as it moved slowly at first over the river rocks.

We did discover one patch of berries that had we not known better, we would have rejoiced over the color for it reminded us of the “white” pumpkins that decorate the season. But . . . we knew better and stayed on the trail in order to avoid Poison Ivy. Yes, it is native. But equally yes, it is a nuisance. Especially if you are allergic.

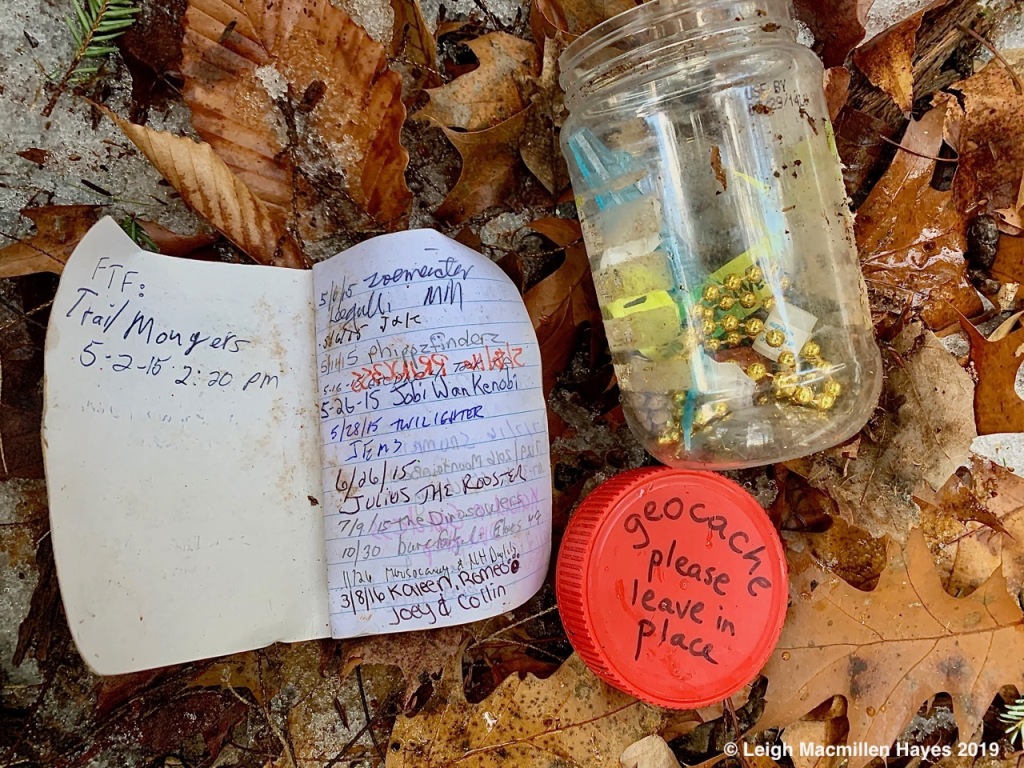

The trail was shaded beside the river and therefore more snow/ice cover had resulted from a slushy weather event yesterday, but that didn’t stop my guy. You see, I had introduced him to Geocaching.com and my guy loves a challenge.

He found the first and read off the trail names of previous discoverers.

I’ll give you a hint other than the one on the site: look for the Grape Fern. ;-)

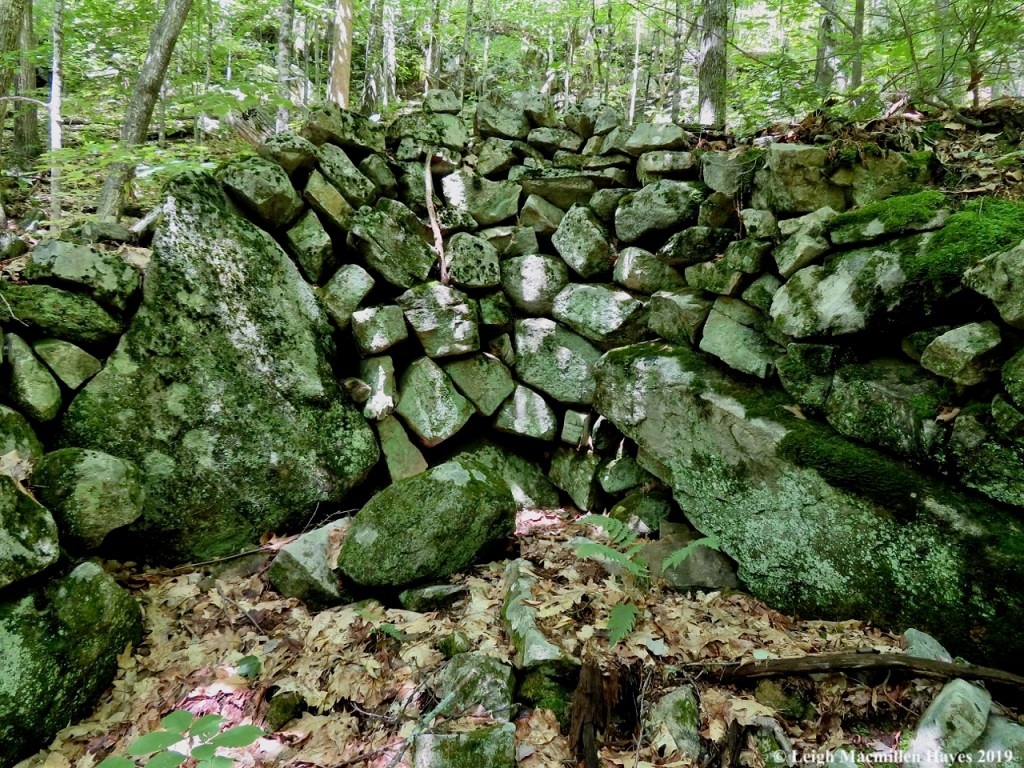

A wee bit further we came upon a couple of granite blocks and wondered where they’d come from and how they’d ended up in this spot.

Following the compass, we eventually made our second geocache find–this one to my credit. It was enough–my guy is hooked and I see geocaching adventures in our future.

If you can’t locate the second site, ask this chipmunk. We saw no squirrels as has been our experience this year (but do expect a payload amount of squirrels next year in response to this year’s acorn and beech nut mast), but the chipmunks dart across trails and roads on frantic missions as they prepare for the coming season.

My guy wasn’t on his own frantic mission for a change and paused beside this burl to point it out to me. That being said, I did chuckle as he moved on while I paused to admire it. Those folds. And curves. Inlets and outlets. It was like arms, long arms, that circled around and over. All because the tree’s growth hormones were disrupted when its metabolism was hijacked by some other organism, be it a virus, fungus, or bacterium.

Our time beside Swift River began to draw to a close as the sun started to set behind the mountains.

We were almost done with the hike when we noticed deer tracks–indicting they’d travelled to and fro with the river as a main point of their destination.

An individual deer print is heart shaped and such described our journey on several levels–as I continued to appreciate Trisha of Upper Saco Valley Land Trust, and also my guy who has put up with me for over three decades.

On this November day, I gave thanks . . . for this day, for these two people, and for all who have traveled this journey with me.

Blessed be.