On my way down the cowpath to retrieve our game camera, I heard among other bird songs, the “Teacha, Teacha, Teacha” of the Ovenbirds. But it wasn’t until I was headed back home a little while later that I actually spied them, which for me is a rare treat–maybe because I don’t spend enough time trying.

In the past, however, it’s always seemed like the minute I get anywhere near them, they stop singing and I can’t find them.

Today, that was different. And I did get to watch. BUT . . . there’s always a BUT in my posts, or so it seems. Anyway, but . . . then I spotted something else.

A beautiful pink Lady’s Slipper. And the leaves of four others–that I hope in future years will bloom.

With fingers frozen because it was raining and the temp was only in the 40˚s on this May day, I headed back to the house, pleased with my finds.

All the while, however, I kept wondering if there are other orchids on our land and so after lunch I donned my rain gear again and headed back into the woods.

First, I stumbled upon this fern, which grows in a vase-shaped form. There’s plenty of it along our stonewalls and at the edge of the field beyond, but while hiking with My Guy yesterday, I pointed some out and called it Interrupted and he wondered why such a name.

Because, I explained, ferns have sterile fronds for photosynthesis and fertile fronds for reproduction and in this case its fertile fronds have interruptions of spore cases in the middle of the blade upon which they grow, while most ferns carry their spores on separate stems or on the undersides of leaflets.

After the spore clusters ripen and drop away, the mid-section of the frond will be “interrupted,” leaving bare space between the leaflets, further reminding us of its name.

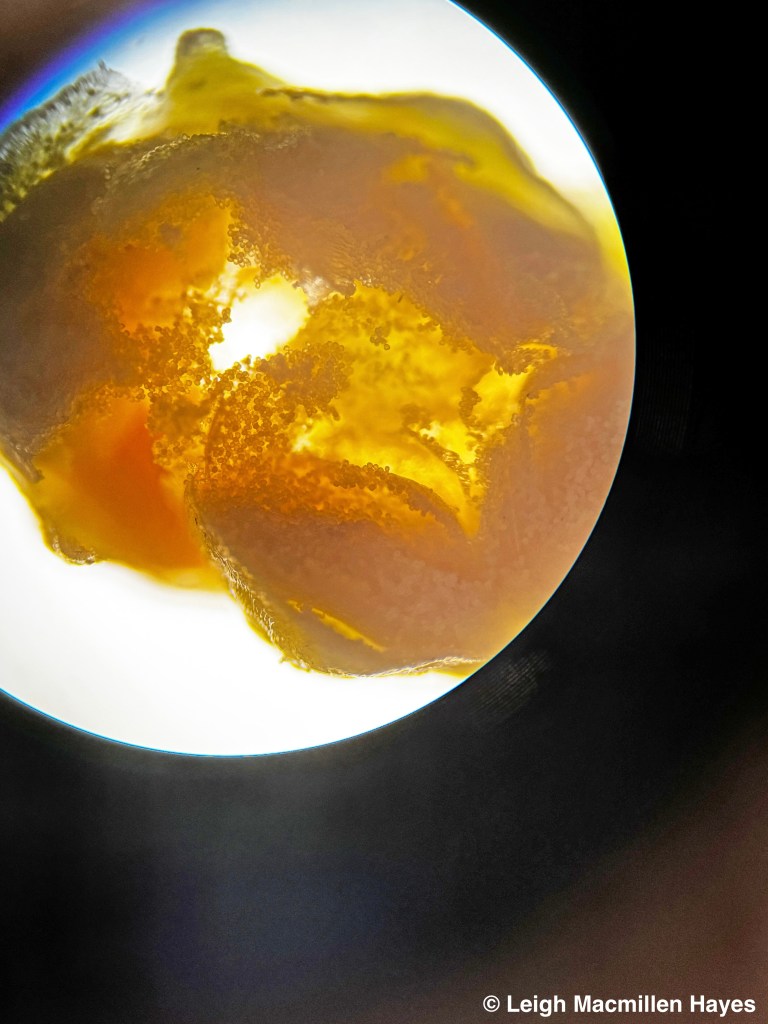

And where there is Interrupted Fern, there is often another member of its family, the Osmundas that is, this being a Cinnamon Fern. One of the differences is that the fertile frond is more like a wand that rises from the center.

There are no leaflets on these fertile fronds, and again, the sporangia are like tiny beads that will turn a warm cinnamon brown when the spores mature. And then, it really will look as if the frond is covered in cinnamon.

While the Interrupted will grow in forests and wetlands, the Cinnamon prefer wetlands, which tells you something about our land. Another that also grows here, though I forgot to photograph it, is their second cousin, the Royal Fern.

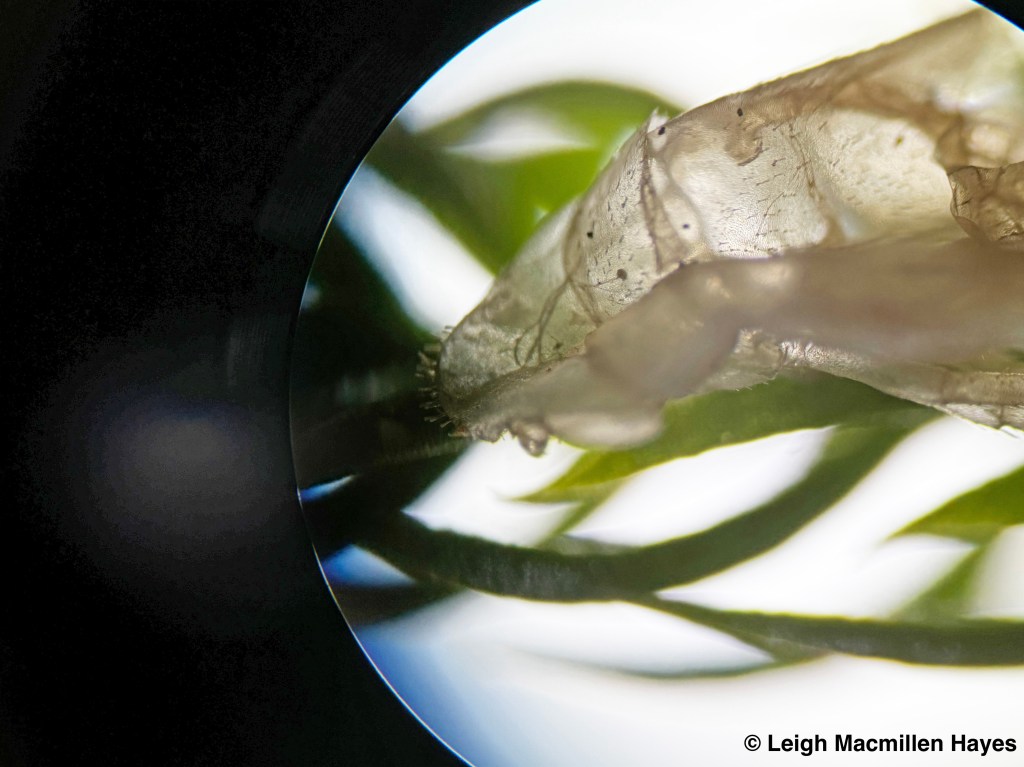

If an Interrupted Fern doesn’t have fertile fronds, it looks very much like a Cinnamon, but one of the key characteristics to tell them apart is that Cinnamons have hairy (wooly) armpits like this one above where you can see the wool on the underside where the leaflet meets the rachis or main stem. And Interrupteds don’t.

Being a bit of a wetland, I shouldn’t have been surprised by my next find, but I was. Jill-in-the-Pulpit! You may think it’s Jack, but like some other plants, including the Canada Mayflower that grows beside these, in order to flower the plant needs the additional energy stores of a second leaf (with three leaflets).

Once I spotted one, I began to notice they were everywhere in one spot on and near the cowpath, but the curious thing–the leaves had been devoured on some. By whom?

And do the leaves also contain Calcium oxalate, which this plant like some others stores in the roots and can cause blisters and other medical problems if consumed? Is that only in humans? So many questions.

That said, my quest now was to seek not only any other Lady’s Slippers, but also Jack-or-Jill in the Pulpits. All told on the latter, I did spot about twenty, but didn’t take time to differentiate how many of each gender.

At last, I reached the powerline that crosses our property and it was there that some feathers decorating a pine sapling surprised me.

A closer look and I found a slew of feathers, all plucked. By one of our predatory birds–we do have Sharp-shinned and Broad-winged Hawks in the neighborhood. Or by another?

We also have a neighborhood Red Fox who passes through our yard and over the stonewall or up the cowpath on a regular basis. Plus Coyotes and Bobcats.

Mr. Fox needs to eat too. And in this case, he marked his territory–right at the end of the ten-second clip.

The question remains–who made a meal of the Turkey?

Again, I do not know, but as I searched for evidence or more remains, look what I found–another Lady’s Slipper hiding among some Low-bush Blueberries.

And so back to my original quest did I return.

And smack dab beside that orchid, another plant that I love, but didn’t realize we hosted–Indian Cucumber Root, with a root that is edible and delicious. And a flower or in this case, flowers, that will delight my soul in a week or less. And yes, this too, is a plant that needs an extra layer of leaves in order to produce a flower. So do we call this a female plant and all plants that only have one level or tier of leaves males?

I don’t know. But I had circled around, zigzagging actually, through the five acres of woods that we own beside our one-acre house lot, and landed back at the first Lady’s Slipper, delightfully decorated with the rain of the day.

Across the way, right where I’d first spotted him, an Ovenbird paused and called. I tried to capture both in a shot, but they are scurry-ers, if that’s a word for scurry they both did as if they were in a hurry and perhaps a wee bit confused. Maybe they were trying to distract me from finding their nest?

I didn’t look for it, but have an idea at least of its whereabouts. And I can only hope that any offspring they produce are well protected cause this is a wild place.

With fingers once again numb, I finally headed home, but first I stopped to check on these Jack-in-the-Pulpits that were the only ones I thought we had, growing as they do by a split-granite bench we made. I remember seeing Jack standing tall in the pulpit one spring as I headed out to the vernal pool, and upon my return someone had nibbled him. Whodunnit?

That said, I decided to place the game camera by all the other Jacks and Jills that I’d found earlier today and I’m curious to see if anymore get nibbled.

All of this because the Ovenbird called. It felt like Thanksgiving. Complete with a Turkey dinner. (Sorry, but I had to say that.)

And to think I thought I knew our land. There’s always something to learn. Or some things!