Maybe I’m a slow learner. Maybe I just need the same lessons over and over again.

Whatever it is, I’m grateful for all who teach me, non-human to human, because there is always something to learn.

This week it was my friend Red who led the class. If you were down the hall in this outdoor school, you may have heard him, for he tends to be quite loud, and a bit critical, when he’s not dining upon a pinecone that is.

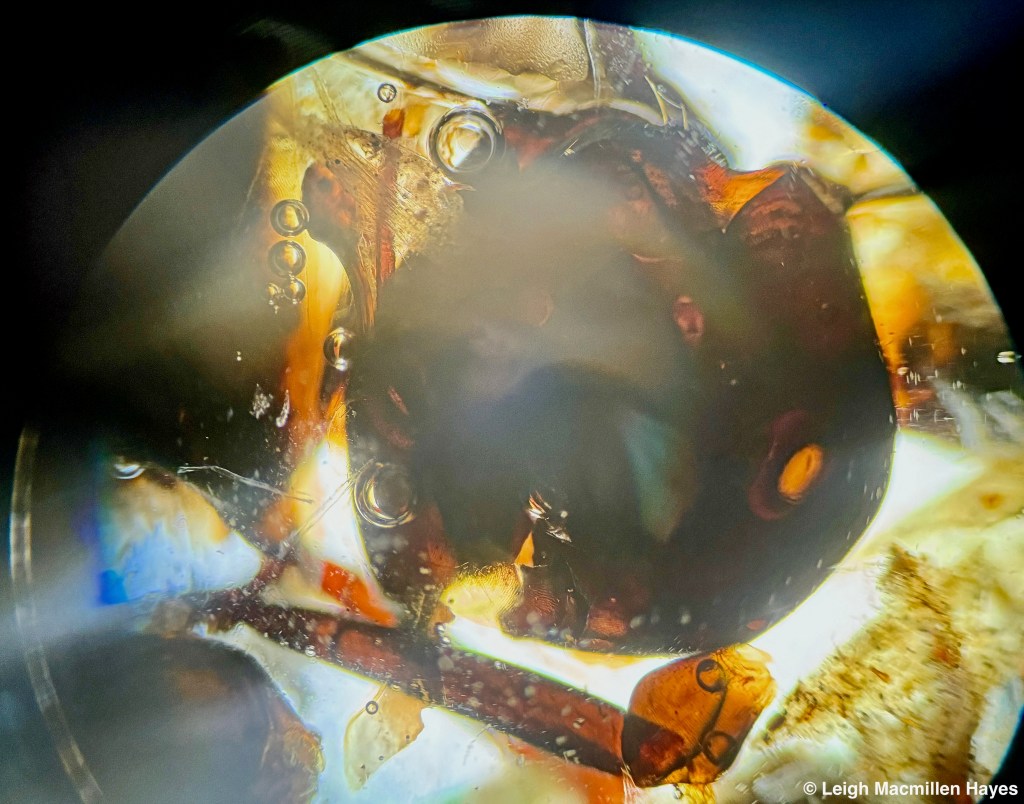

His plan, as it often is, was to strip the cone of its protective scales and seek the tiny seeds tucked in by the core or cob of the cone. Each scale contains two winged (think samara that help the seeds flutter toward the earth when its warm enough for the scales to open on their own) seeds and to me it seems like a lot of work for a little gain.

But if you’ve ever watched a Red Squirrel at work, you’ve noticed they are quick and can zip through one cone in mere minutes. Of course, it helps that they don’t worry about the “trash” and just let the scales and discarded seed coverings or pods, and even half consumed cones and cobs pile up in a garbage pile known as a midden. Spotting one of these is a sure sign you’ve entered Red’s classroom. And if you pause and look around, surely you’ll find many more middens. After all, Red Squirrels are voracious consumers. But again, given the size of the seeds, they need to be.

So here’s lesson #1: Leave the scraps. Oh wait, not on our indoor dining tables, but in the woods. And not our food in the woods, unless you are composting. But downed trees and snags and leaves and all that will replenish the earth, just as my squirrel’s garbage will do.

I should clarify that Red shares the school with many others who have their own classrooms and I’m sure when I finish my latest assignments I’ll have more to learn from the porcupines and deer and hare and coyotes and foxes and bobcats and yada, yada, yada who live under the mixed forest canopy.

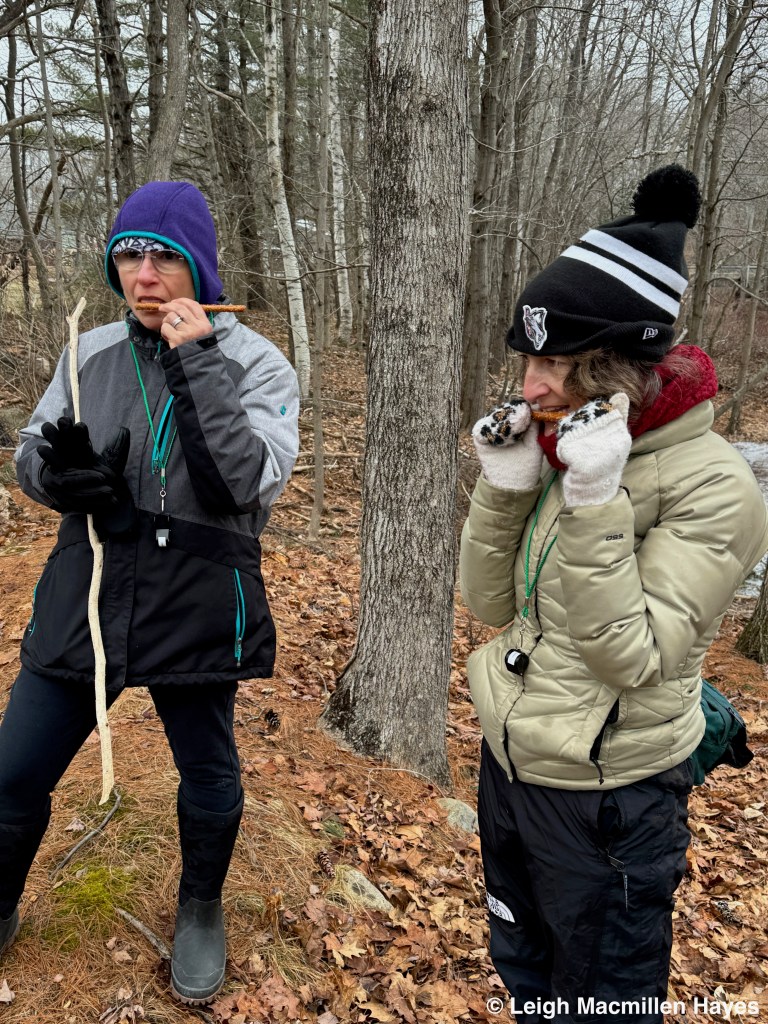

The sight of so many Eastern Hemlock twigs on the forest floor told me I’d stepped into Porky’s room so I looked for evidence, wondering if he was at his desk or not.

Lesson #2: Slow down and observe.

The answer was no, but he’d left his calling card on a dangling twig and so I know where I might find him should a prickly question enter my mind.

Because I was told by Red to slow down and observe, I noticed another spot where he’d visited and this time his midden was of a different sort in the form of snipped twigs. Much smaller snips than Porky drops, which is a good way to tell the two critter’s food source apart.

Just as Porky’s twigs had been cut with the rodent diagonal, so were Red’s.

I noted that he hadn’t eaten the buds at the tip of the twig, but once I flipped one over I discovered numerous buds or seed pods had been dined upon.

Lesson #3: Check twigs more often. And remember, this year was not a mast year for Eastern White Pines, so Red has to supplement with hemlock buds and cones. (And also remember, cones on hemlocks are not called pinecones because they don’t grow on pine trees. Conifer refers to cone-bearing, so both pines and hemlocks are coniferous trees.)

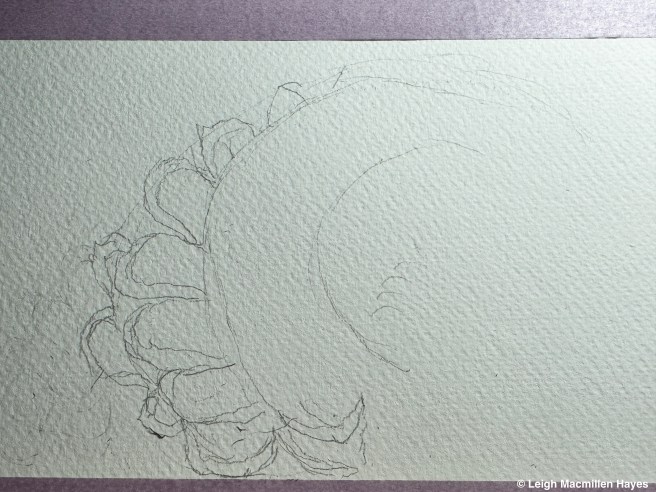

Back inside I decide to sketch a pinecone. It was a sketch I’d started months ago, but abandoned because it seemed to difficult to draw.

But then, thanks to Red, a realization came to mind.

Lesson #4: Pinecones have overlapping bracts or scales that protect those seeds developing inside of them. They close in the dark and open in light, especially on sunny days and it is then that the seeds become airborne on their samaras. And the bracts or scales grow in spirals around the core or what I think of as a cob. I knew that, but had forgotten it until I decided to sketch.

And so I drew some guidelines to aid me as I tried to recreate the cone’s spiral staircase.

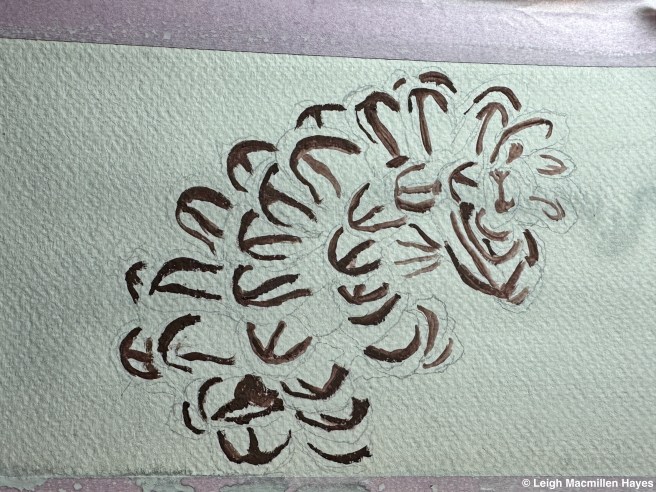

It was fun to watch it grow and realize each cone actually fans out in a Fibonacci spiral sequence. It’s an amazing wonder of nature.

Feeling my drawing was complete, I began to add color in the form of gouache paint, scale by scale.

And slowly, the painting began to represent a cone . . . at least in my mind’s eye.

A dash more color and voila–my amateur attempt at painting a pinecone. I have to admit, I was rather tickled because I really didn’t think I could pull this one off. But I have my art teacher, the talented Jessie Lozanski, to thank for giving me the confidence to try.

And I have Red, my other teacher, to thank for the lessons because it was in watching him turn the cob ever so effortlessly that I was reminded about the cone’s spiral.

And so I tried to honor him as well. I may be a teacher, but I’ll always be a student.

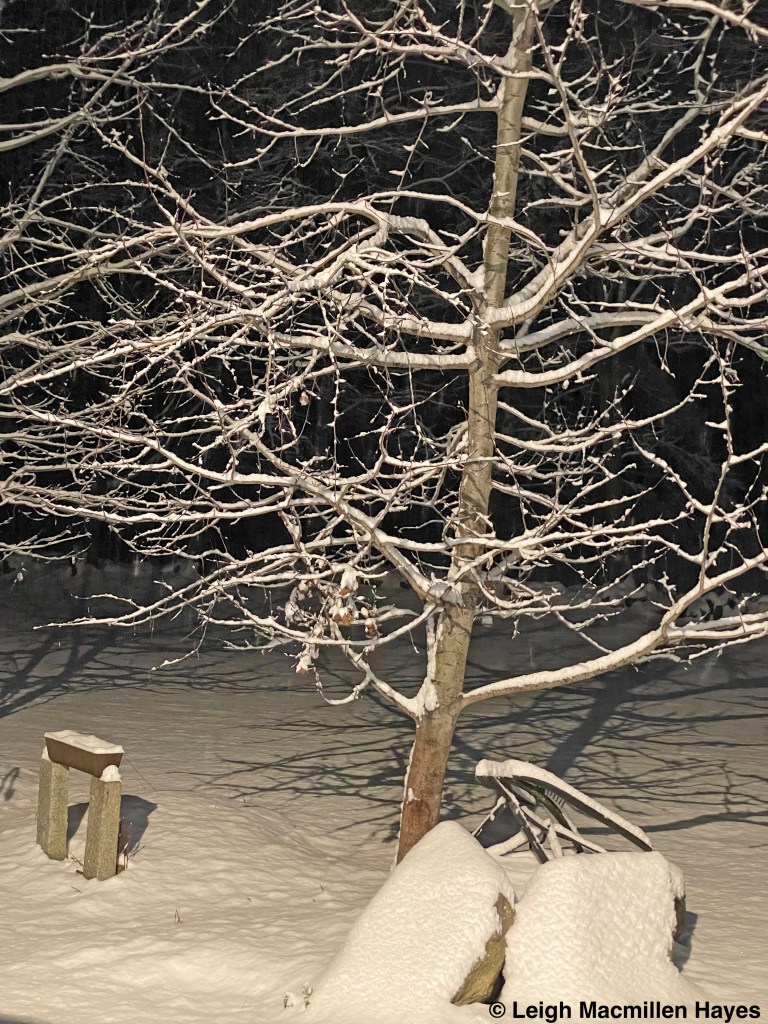

Lesson #5: As we head into this new year, I hope you’ll join me in slowing down and noticing and honoring. Especially outdoors. Or even out your window.

I’m forever grateful to Red and all the other teachers who come in many forms, not just as mammals, for the amazing lessons I’ve learned and can’t wait for the next class.