Given the incredible tracking right out the back door this afternoon, you would think that would be the focus of this post. I mean really, Red Fox duo, Coyote duo at least, Red and Gray Squirrels, Ermine, Bobcat, Snowshoe Hare, White-tailed Deer, and of course, Turkey and Ruffed Grouse.

But . . . I find myself returning to the topic that has fascinated me as much as the mammal and bird stories written on the snow . . . spiders and insects. And actually, it’s a story or two or three that have taken place over the last couple of weeks as I wandered through the woods that surround our home almost daily. It’s been a rare day that I didn’t meet one of these tiny beings. It seems that whether the temperature is in the single digits or 40˚s, they are out and about, even in rain and snow.

And the beauty of observing and learning about these champions of winter is that there are so few of them, I can actually retain their common names from one day to the next. That said, often there are surprises in the mix as I’ve reported in the past two episodes of Spiders and Insects. (See Spiders and Insects: A Winter Love Story and Spiders and Insects: And More New Learnings)

On a daily basis I continue to meet Long-jawed Orbweavers such as this green female. Though she looks huge, she’s less than a half inch in size. And check out those hairy legs.

As my friend, Bruce, determined, the reason I see so many Orbweavers is because I live in a rather damp area, or perhaps I should say moist, it sounds so much more pleasant, where Snow Fleas (Collembola) are abundant and that is the spider’s main food source.

Today’s spider lesson was a bit different and it happened upon several occasions–as I went in for a closer look, unlike the Orbweavers, the ground spiders I met became coy and covered their heads, appearing to freeze in an attempt to possibly make me believe they were dead.

Of course, they can’t really make this decision, but rather are reacting by instinct–I was the predator and they the prey–not a role they usually assume.

But this story is about more than the spiders, for one of my new favorite winter insects, the Snow Fly, a wingless Crane Fly, has a strong presence around these parts. This is a male, identified by its abdominal tips.

The long ovipositor identifies this one as a female.

But, there’s something curious going on here. I’ve said before that they self-amputate their legs if the temperature is too cold and they need to keep the freeze from reaching their organs.

Do you see that she has only four legs, the hind two missing?

From some research, I’ve discovered that as she and her kin walk across the snow, the cold surface causes water in the legs to freeze; in the process of crystallizing, heat is released in the leg’s tarsus (tip–think toes), thus signaling danger to neurons and a specialized muscle at the hip joint contracts forcefully until the leg snaps off! Can you imagine? All this to survive in a season to which you were created to exist.

With four legs, one can still navigate. I found another with two legs on one side and one on the other. He still had motion, but was slower and more awkward, and I feared for his future.

Another learning occurred these past two weeks. When I took the time to stand still, I noticed that sometimes the females walked (scrambled in some cases) to vegetation.

And then headed down a stem, and I imagined she was on her way to the subnivean layer between the ground and snow where perhaps she’d find a mate in that cavity.

Not far from such activity I had the good grace to meet two more snow specialists: Snow Scorpionflies. How I ever spotted them, I’ll never know, for so small are they, but I’ve trained my eyes to notice anomalies, and sometimes its the slightest movement that draws my attention . . . and gladdens my heart.

And then I met another female Snow Fly. When I first spotted her, she was on the edge of the woods but moving quickly. Curious, I decided to watch her to see where she might venture.

Much to my surprise, she crossed a main snowmobile trail that is at least six feet wide, and then continued.

Do you see her? She’s in the midst of the Sheep Laurel that is sticking up above the snow.

Eventually, she reached a leaf, and I had to really look to see her, for so well did she blend in to her surroundings. By this point, she was about fifteen feet from where we’d first met, and only a few minutes had passed.

Why the midwinter journeys? From what I’ve read, it may be to avoid inbreeding–if you live in a group chamber below the snow’s surface, that doesn’t bode well for genetic diversity.

But if you venture forth, maybe you can find a guy from another family and hunker down with him. And if you want to avoid being observed by the local Paparazzi, or birds I suppose, find vegetation that matches your coloring. And then slip into the wedding chamber.

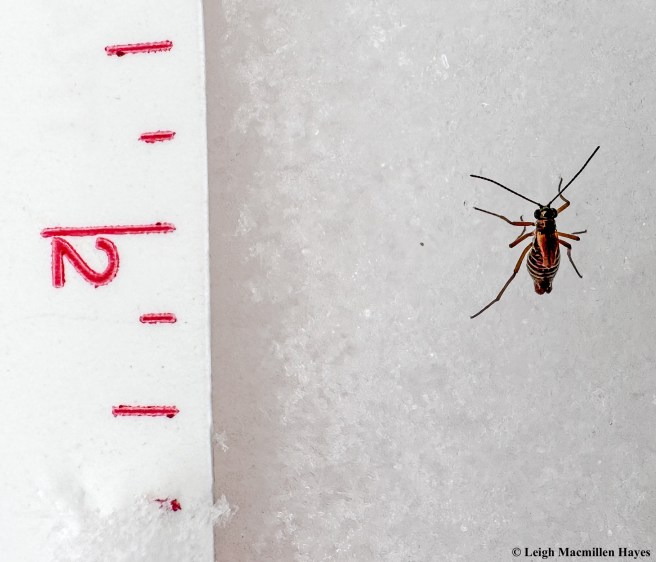

Okay, so I have to admit that I tried to be a matchmaker and brought a female atop my tracking card to meet a male about a half a mile away. Surely this was a pair that couldn’t resist the possibilities.

They took one look at each other and turned the other way, running as fast as their legs could carry them.

Matchmaker, matchmaker, don’t interfere!

And as I said, each time I focus on the spiders and insects, which is almost every day, I am surprised by my findings. Today, it was two Inch Worms. Or more likely, Half Inch Worms.

Spiders and Insects: yes, the love affair does continue. It’s a whole other reason to be outside observing no matter the weather.