The text arrived from one of my first playmates on Wednesday. “Good morning,” she wrote, “Just wanted to give you a heads up my fat and sassy Juncos are headed your way. Only had a couple yesterday and none this morning. Hope they had a safe trip! Blow them a kiss for me. Hugs.”

A few hours letter I wrote back that I’d let her know when they arrived.

And a few minutes, voilà! My second text to Kate: “No sooner said than BINGO! I looked out the back door and there were three!”

On Thursday afternoon, the Bluebirds arrived. Kate told me she’d had three couples all winter in Connecticut. “They are so stunning! They seem to be the kindest of breeds. They don’t squabble as much as others and share better.”

After that, it was a Tree Sparrow. And many more Juncos each day.

And today, the Chickadees and Tufted Titmice and Bluejays, of course, but also Goldfinches, and one Tree Sparrow, and Mourning Doves, and Red-breasted and White-breasted Nuthatches, and Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers, and I’m sure others that I’m missing, and suddenly, the feeders were busy. Toss into the mix Red and Gray Squirrels, and Crows, though the latter stayed about ten feet away from the action, while the former got right into it, and it was a full house.

This afternoon, I interrupted the action for a few minutes when I headed out the back door to go for a tramp in the woods and had just reached an opening when I heard, then saw this guy and knew that our resident Red-shouldered Hawk had returned.

According to Stan Tekiela’s Birds of Prey of the Northeast, “Adults return to the same nest and territory for many years; the young also return.”

Welcome home!

I had no sooner lost sight of the hawk, when movement from another source caught my eye.

Flying from the ground up to a tree limb was a Barred Owl. And my heart was even happier than it had been.

We spent a few minutes together and I gave great thanks also that the vernal pool over which the owl perched is still rather frozen. No frogs or salamanders would be on the menu yet. I did, however, worry about the birds in my yard, but there was nothing I could do.

Except, that is, watch my friend for a few more minutes before waving goodbye to him and moving on.

And that’s when I heard a song, or rather many songs, that took me back to a summer morning and realized that as much as I don’t want winter to come to an end this week, the time has come because there is so much more to see and welcome and wonder about. The Red-winged Blackbirds were in a large flock with Grackles, and Robins, and more Crows. And the chorus was most delightful.

I’d say the female Hairy Woodpecker was much quieter than the others, but it was her inflight song that encouraged me to look for her.

I just hope it wasn’t Emerald Ash Borers she was seeking as she drilled a few test holes in the tree. Of course, if she can help control them, then that’s a good thing.

My journey led me to a local brook where the Mallard flock is spreading out more as the ice is receding quickly during these suddenly 50˚ days.

That said, they are still there.

He preened . . .

as she looked on.

Others did what we should all consider doing on a Sunday afternoon: stick our heads under our wings and take a nap.

But I didn’t. How about you?

Upon a second brook that flows into the first, another species caught me by surprise as I rarely see it in this place. A female Common Goldeneye. I’ve always had a problem with the descriptor “common.” That prominent golden eye is hardly common in my book.

Moseying along, I realized it wasn’t just birds who were greeting the day. Chipmunks have been dashing about on the snow for the last week or two, taking advantage of any acorns the squirrels may have hoarded. (And birdseed–as I watched one stuff its cheeks the other day.)

One critter that surprised me was a Carpenter Ant making its way toward a boulder rather than a tree. Though I see the exoskeletons of these ants in Pileated Woodpecker scat all the time and even found some fine specimens in our woods today, I don’t recall ever spotting one on snow before.

Speaking of Pileated Woodpeckers, their freshly excavated holes are dripping with sap and by this hole I found a couple of Winter Fireflies. So, um, Winter Fireflies are fond of Maple Sap. In fact, some call them Sap-bucket Beetles. But White Pine sap? Do you know how sticky it is? As in, you can practically glue =-your-fingers-together sticky.

When I first spotted these two, I wondered if the sap might have given them pause. Were they stuck?

But then there was movement and in that moment, all was good with the world.

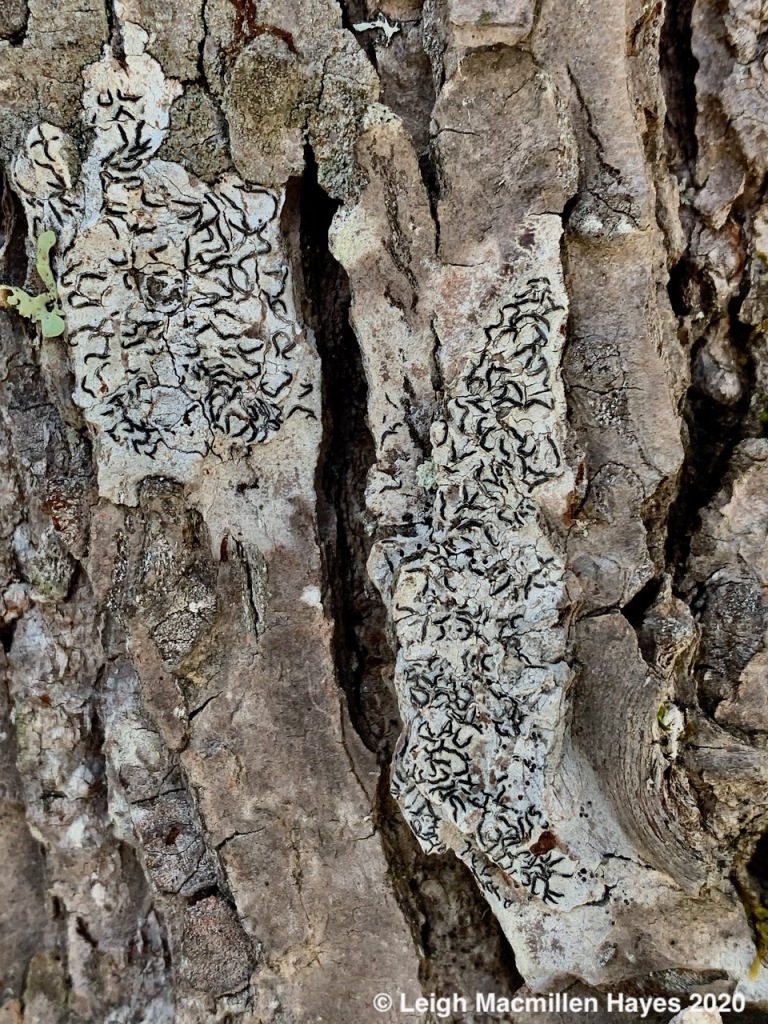

I had one more discovery to make–actually, it’s been my quest this year to find this species and its relative who is only about a half inch longer.

But I must have missed the mass emergence of Small Winter Stoneflies, and their cousins, Winter Stoneflies, for like today, I’ve only seen one or three or maybe five on any particular occasion near these brooks, when in the past there were so many more. Might last summer’s drought and water conditions be the reason for so few? After all, these species are highly sensitive to pollution and thus, are indicators of excellent water quality. I have to hope that I just missed the right day.

After the Stonefly discovery, I did find one more thing that always brings me around to the cycle of life. A small bird was plucked and became the meal of a larger predator.

Curiously, some feathers were stuck to the bark of the tree . . .

My thought was that the predator sat high above, and let the plucked feathers drop and being a pine, a few stuck to the sap, or maybe just to the rough bark. Or maybe the bird was consumed right there on the side of the trunk.

I don’t know and I don’t know who the predator was, but energy was offered and sunshine turned into seeds and insects that fattened up the smaller bird were passed on to the bigger critter.

Perhaps the Barred Owl knows the whole story. Or the Red-shouldered Hawk.

All I know is that I gave thanks for this day to wander and wonder and be greeted by so many who are all a part of my neighborhood. Well, really, I’m a part of their neighborhood, and I appreciate that they share it with me.