The morning began as Tuesdays do in my current world, with a visit to a Greater Lovell Land Trust property accompanied by a group of curious naturalists we know as docents who love to do deep dives on every little thing that we encounter and in the midst we share a brain. A collective brain is the only kind to have, in my opinion, because we each bring different knowledge or questions to the plate.

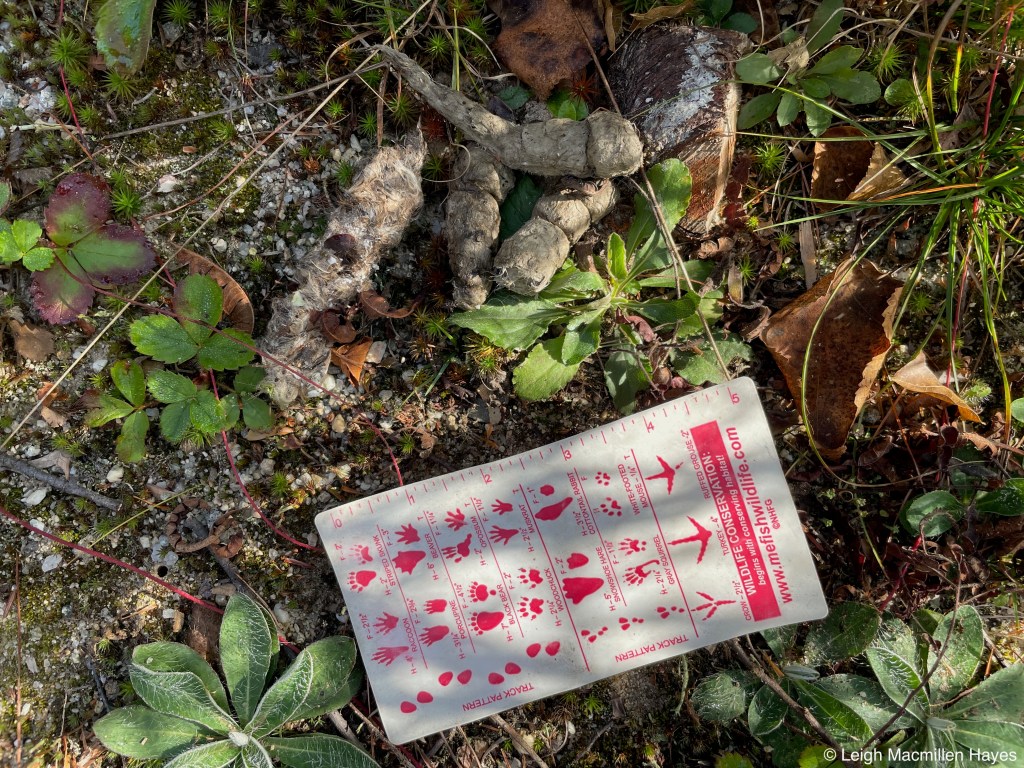

And so it was when we first encountered what could have been a hair ball of sorts and then discovered this hair-filled scat about a yard beyond. And near it another “hair ball.” Based on size and structure we determined the scat belonged to a bobcat, and thought that the hair balls made sense as maybe the cat had to cough up some of the hair of the mammal consumed. What did it eat? Well, we know both snowshoe hare and deer frequent this place and so it could have been either.

A little further down the trail we reached a beaver lodge that some of us had seen under construction in August 2022, and gathered game camera photos over the course of time, and spotted all kinds of sign of activity each time we visited, until that is, May. When it rained. And rained. And rained. In a torrential manner. And the dam the beavers had built was breached. And they disappeared. And we know not their fate.

But the beauty of a beaver pond is that once breached, change happens and other critters take advantage of the space and there’s so much possibility and we can’t wait to watch how this space, one in which we could walk prior to August 2022, will evolve and other flora and fauna may move in until another beaver family takes up residence and changes it again.

About an hour or so after departing, a call came. Well, really, it was a typed message. But as my morning peeps know, shout, “Kill site,” and no matter what I might be focused upon, I’ll come running.

The message included a few photos of a mammal skeleton and a thought that it might be a beaver that had become the meal because it was located close to another beaver pond. Beaver ponds are plentiful in the landscape of western Maine.

After a few messages back and forth, the writer and I agreed to meet and walk to this site. Take a look. The meal this skeleton became had been consumed months ago, I suspect in the winter, given how much was missing, including the head. And even after any hide and meat had been eaten, the bones continue to provide calcium for rodents seeking such.

Since my guide suspected beaver, I knew I had to slow my brain down and assess the evidence. My, what long toe nails. And though some were broken, it seemed obvious to me that they were all oriented to the front of the foot. Plus, there was no evidence of webbing.

A bigger clue was observed with a closer look. Barbed quills sticking into the spine. I pulled one out and we examined it.

And about a foot away, a pile of quills, with vegetation growing through them adding to the age of the kill site.

And hiding there also, as if stuck into the ground, a quilled tail.

Did you know that porcupines have a variety of hair? For winter insulation, they have dark, wooly underfur. In addition, there are long guard hairs, short, soft bristles on the tail’s underside, stout whiskers, and then there are those pesky quills.

They aren’t pesky to the porcupine; just us and our pets and any animal that might choose to or accidentally encounter a porcupine.

Overall, a porcupine sports about 30,000 quills, and within one square inch on its back, you might count up to one hundred, as demonstrated by my jar of toothpicks.

The quills are 1 – 4 inches in length and lined with a foam-like material composed of many tiny air cells, thus their round, hollow look. There are no quills on the porcupine’s face, belly, or inside its legs.

Look at that nose. Soft hair indeed. As is the stomach. A fisher, which is a member of the weasal family and not a cat, will attack the porcupine’s face repeatedly.

Fishers and bobcats also have been known to flip a porcupine onto its back and then go for the belly. That doesn’t mean that they don’t get quilled, for in moments of danger, the porcupine instinctively raises its quills and positions itself with its back facing the predator, showcasing its formidable defensive strategy. but the predator does get a meal.

This dinner had long ago been consumed as I said. But was it a fisher or a bobcat who scored this meal? We’ll never know, but I give great thanks to Dixie and Red and their best friend Lee, for being such great scouts and sharing the results of their hunt with me.

Found a kill site? Give me a shout and I’ll come running.

Gre

LikeLike

Huh?

LikeLike