It occurs every year, autumn that is. But this year it hasn’t even started and already feels different. In the past week, My Guy and I have followed many a trail or waterway, both on foot and by sea, oops, I mean kayak on local lakes and ponds, and every offering has been unique.

Some, such as this, being Brownfield Bog as we locals know it, or Major Gregory Sanborn Wildlife Management Area as the State of Maine knows it, took us by complete surprise. The last time we’d wandered this way together was in the spring, when despite wearing Muck Boots, we could not travel some parts of the trail because the water was so high. That was in the Time-We-Actually-Experienced-Rain. That time has long since passed and now western Maine is in a severe drought and don’t the Lilypads know it. What about all the mammals and birds and insects that depend on this water? It was an eerily quiet walk in a place that is usually alive with action.

Where the Old Course of the Saco River crosses through the bog, there was some water. But still, not enough. And we know of other areas of the Old Course, such as in Fryeburg Harbor, where there is no water.

As for the Saco, it too, was incredibly low and sandbars were more the norm.

Other adventures found us paddling our favorite pond.

And bushwhacking around another bog.

What kept making itself known to us–the fact that the trees are turning much too soon, and many leaves aren’t even turning, but rather drying up and falling.

That meant that some paths or bushwhacks found us crunching the dried leaves with each step we took. We could hardly sneak up on a Moose or a Bear, or even a Squirrel.

Despite such dry conditions, we did find the varied colors of Wild Raisins or Witherod drupes dangling in clusters below their leaves.

And Winterberries showing off their enticing red hues–ready to attract birds and maybe become part of our holiday decorations. Only a few branches for us, mind you. We leave the rest to the critters because we know their importance in the food chain.

Late summer flowers were also in bloom, including the brilliant color of the Cardinal Flower.

And in a contrast to the red, there were Ladies’ Tresses, a wild orchid, one of the few with a fragrance if you can bend low enough to smell it.

I think one of the greatest wonders is how many variations there are on a theme, in this case flowers for take a look at the Pilewort or American Burnweed, this one growing upon a Beaver Lodge.

What you are looking at is the flower heads: They are about a ¼ across and petal-less. The inner bracts, with their purplish tips form a ½-inch tube exposing just the yellowish to creamy white stamens at the top. And the seeds are teeny tiny, as you can see, with tufts of white hairs to carry them like parachutes upon a breeze.

Along one trail, we spotted another teeny tiny display that surprised us due to the fact that we haven’t seen many mushrooms this summer. But the Orange Peel Fungus apparently had enough moisture, at least to produce these two forms.

Critters were also a part of our sightings and several times we encountered young Northern Water Snakes, not more than two pencils in length.

In another spot where we expected to see Water Snakes, we instead met a Garter. Mind you, none of these wanted to spend any amount of time with us.

And despite the cooler morning temps that we’ve been experiencing, including lows in the mid-30˚s the past few days, or more likely, because of those temps, the Painted Turtles were still basking, soaking up the sun’s warmth. I love how they stick out their legs to absorb more warmth. It truly looks like a Yoga position, and I know this personally because along one of the trails we traveled in the past week, My Guy showed me several poses he’s learned recently. He also showed me those he struggles to perform.

Not all turtles were of the same size, and this was a tiny one, who stayed on this log for at least two hours as we spotted it before we embarked on a bushwhack and it was still there when we returned, though it had changed its position. And gave me a wary look.

My Dragonfly fetish was also fulfilled for the Darners and Skimmers continue to fly and occasionally pause. Well, the Skimmers often pause, but the Darners are usually on the wing–patrolling territory while looking for a meal, and even more so, a mate. That’s why it’s always a moment of joy for me when one stops and my admiration kicks up a few notches. In fact, it’s the notch in the side thoratic markings that help with ID–in this case a Canada Darner. I’ve discovered this summer that they are numerous ’round these parts.

While the Darners are on the largish size in the dragonfly world, most of the Skimmers that are still flying are much smaller. The Blue Dasher, as this is, is probably considered medium in size.

What a display, no matter how big, with the blues and blacks and greens contrasting with the Red Maple leaf’s hues.

And then there’s the dragonfly’s shadow. It’s almost like it was a different creature.

My surprise was full of delight when I realized as I floated beside a Beaver Lodge, that I was watching female Amberwings deposit eggs into the water as they tapped their abdomens upon it. I rarely spot Amberwings, and yet they were so common in this spot.

And overlooking all the action, perhaps not only to defend its territory, but also to eat anything that got in the way, a Slaty Blue Skimmer, twice the size at least of the Amberwings and Blue Dasher.

Birds, too, were part of the scenery wherever we were. This Eastern Phoebe spent moments on end looking about, from one side to the other, and then in a flash, flew to some vegetation below, grabbed an invisible-to-me insect, and flew off.

Much to the surprise of both of us, despite the loud crackling of leaves and branches upon which we walked in one place, we didn’t scare all the Wood Ducks off, and enjoyed spending a few minutes with this Momma and Teenager. Usually, this species flies off before we spot them on the water.

Even the male hung out and when I suggested to My Guy that he look at it through the monocular, he was certain he really didn’t need to because he could see it without any aid. And then he did. And “Oh wow!” was the reaction. And I knew he’d finally seen a male Wood Duck–for the first time. And that moment will remain with me forever.

One of our other favorite moments occurred on our favorite pond, where we first spotted a Bald Eagle on a rock that the low water had exposed. And then it flew. As birds do.

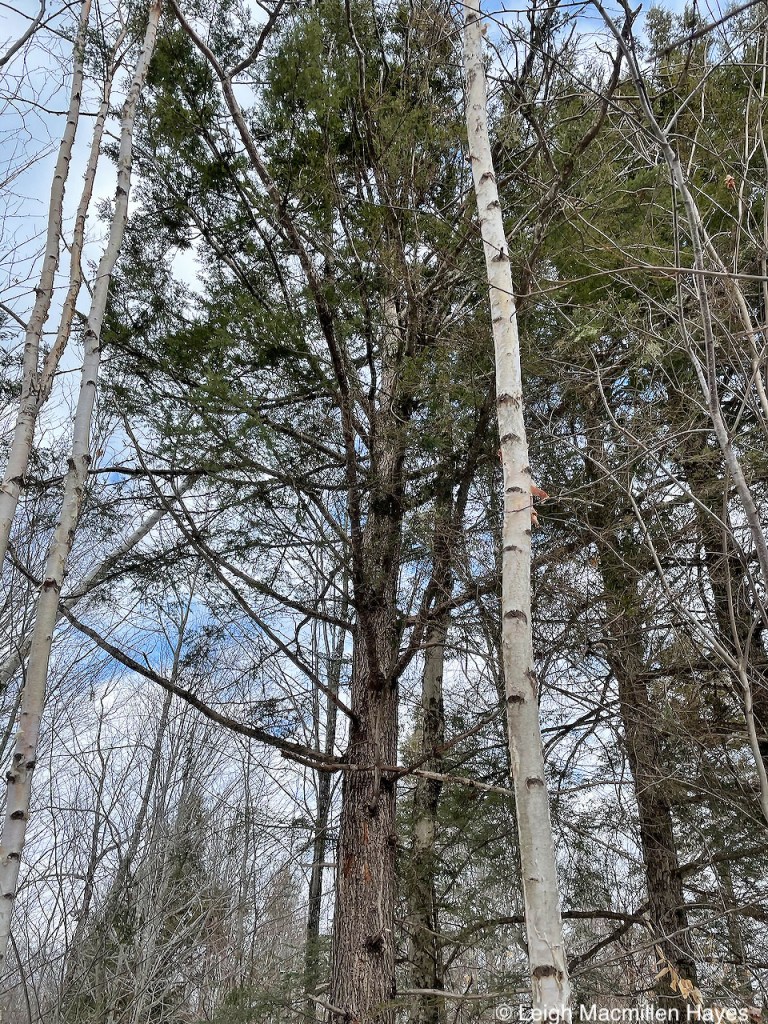

And we followed it with our eyes, and watched it land above us in a White PIne.

And thus, we spent a good twenty minutes with it, admiring from our kayaks below.

The Bald Eagle was sighted not to far from our favorite Beaver City–where we know of at least five lodges located within a football field-sized area. And this one above had been abandoned for the last few years.

But fresh mud and fresh wood told us that someone was home. Probably more than one someones. We love the possibilities. The mudding is an important act–preparing for winter by coating the outside and closing up any holes or airways that might let cold air penetrate. Of course, the “smoke hole” at the top will remain, much like a chimney in our homes.

Just a Beaver channel and a hundred yards away, another of the five lodges also showed signs of winter preparation. It’s a busy neighborhood.

No matter where or how we traversed, one of the things that stood out to us is that despite the autumnal equinox being September 22 at 2:19pm. fall is already here thanks to the summer’s drought.

It’s usually mid-October when we begin to celebrate the color change–that time when Chlorophyll, the green pigment we associate with summer, and necessary for photosynthesis, slows and then stops manufacturing food, and the leaves go on strike.

Veins that carried fluids via the xylem and phloem close off, trapping sugars, and promoting the production of anthocyanin, the red color we associate with Red Maples like these.

Tonight, as I finish writing, we are on the Cusp of Autumn, which is about seventeen hours away. But this year, I think it’s already here and if you have planned a fall foliage tour for mid-October I hope you won’t be too disappointed. I suspect we’ll not have many leaves left on the trees by that point.

But . . . maybe I’m wrong. There’s always that possibility.

No matter what–Happy Autumnal Equinox!