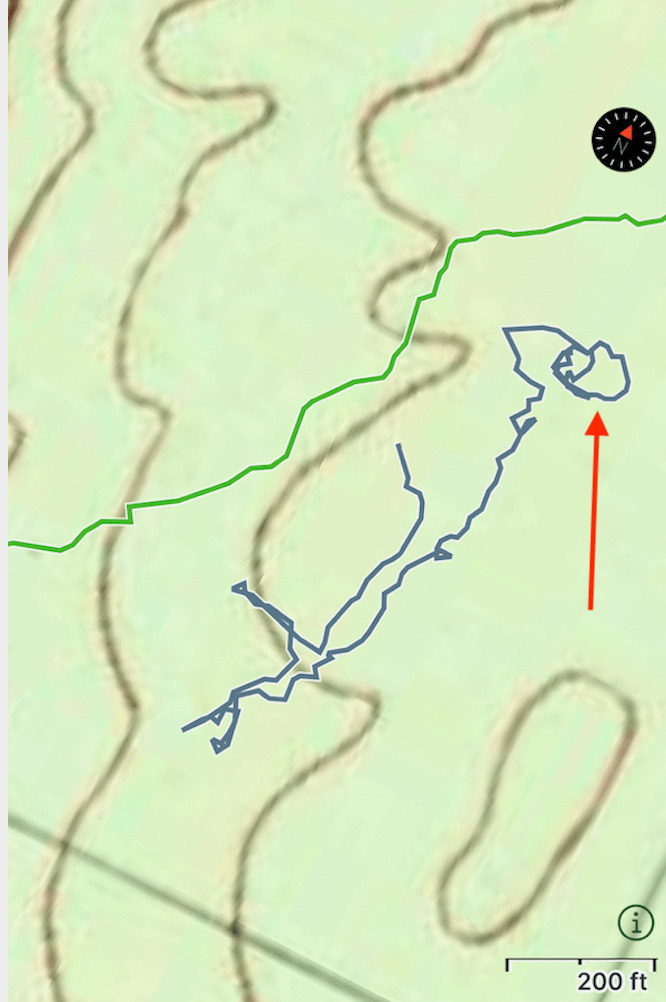

We’ve traipsed through these woods before, My Guy and I, but always, there’s the old to see and the new to appreciate. And so today we visited both.

By the shape of the forest road we walked, I could have driven another mile before parking. But . . . I like to walk. And besides, you can’t appreciate all the beauty that surrounds you on a wet autumn day if you fly in at 60 miles per hour. Or even at 20!

And because we walked, we found an off-shoot trail that led us to a sweet spot we’d not visited before along Great Brook, where we stood for a few moments watching and listening and smelling as the water cascaded over the rocks.

Once we got to the trailhead after passing around a gate, we followed another old road for a ways, up and down over a few little hills, and then, because memory was on our side, as the road curved to the right and the stonewall began on the left, we knew it was time to turn and begin a bushwhack up a road that hasn’t seen much use in decades. It was there that we spied the first witness. A tree standing over a marker. By the way the tree is growing around the sign, it’s obvious that it’s been keeping watch for decades.

So if that was the witness post, where was the survey marker? Atop a rock at the base of the witness tree. And 1965 would be the year that the sighting was first made.

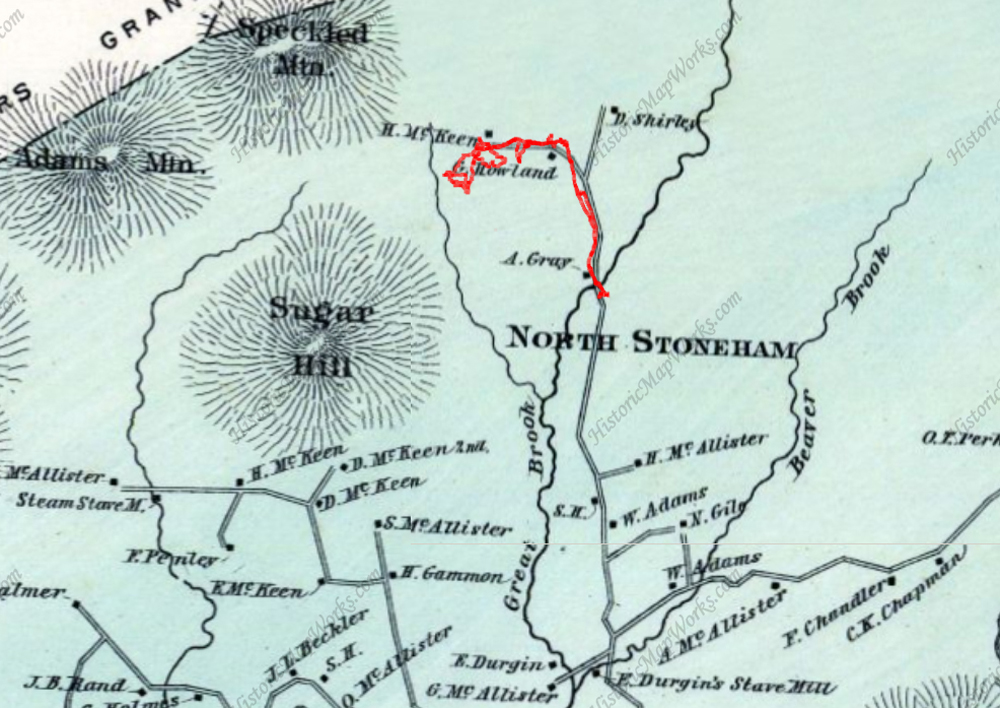

Eventually we reached the first of the foundations because even when we are what seems to be deep in the woods, we’re in the middle of a place that was once somewhere — someone’s neighborhood. In this case, according to the 1858 map, we were visiting the Durgins.

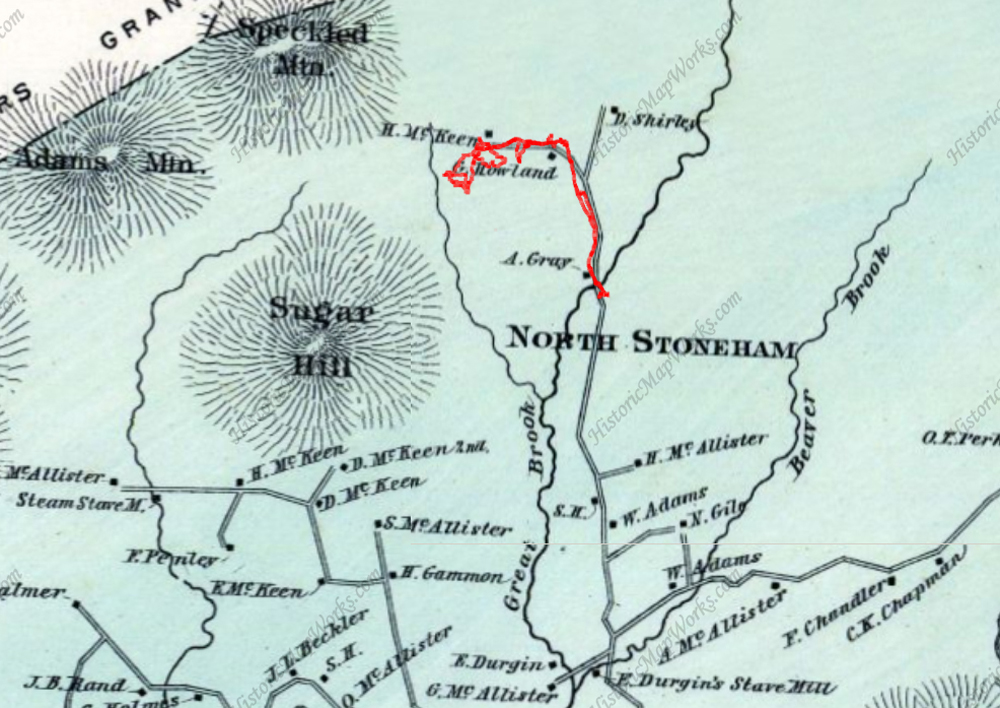

My friend, Jinnie Mae (RIP), was an historian and tech guru and years ago she overlaid part of the bushwhack we did today on an 1858 map. You can see the name E. Durgin on that.

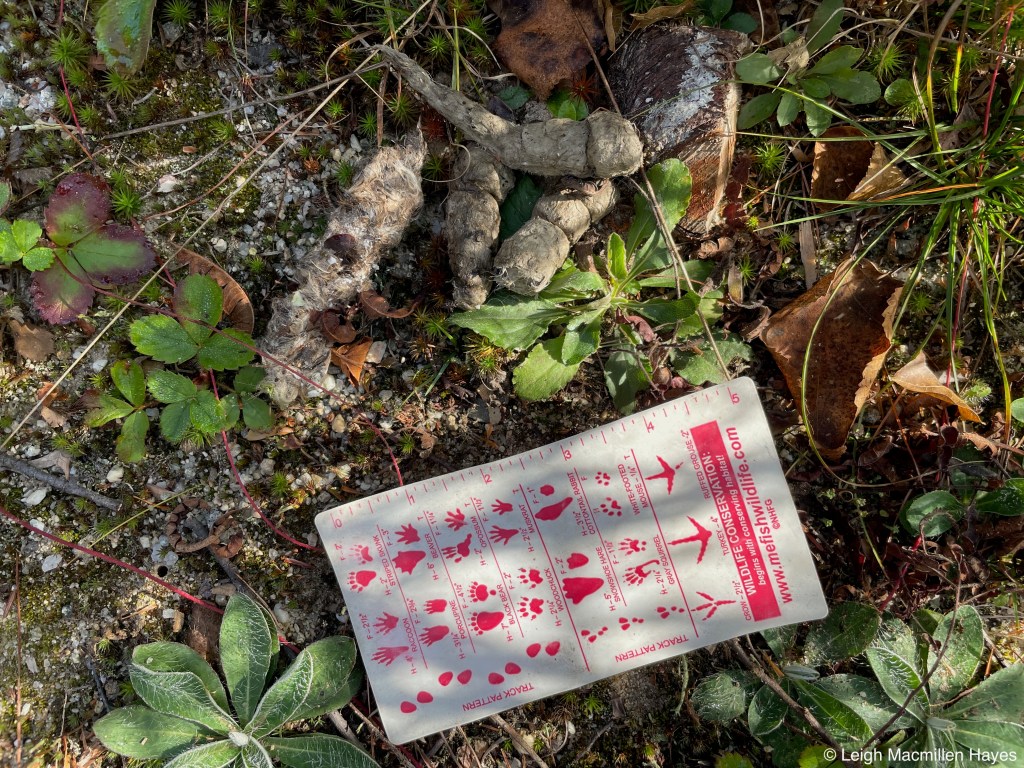

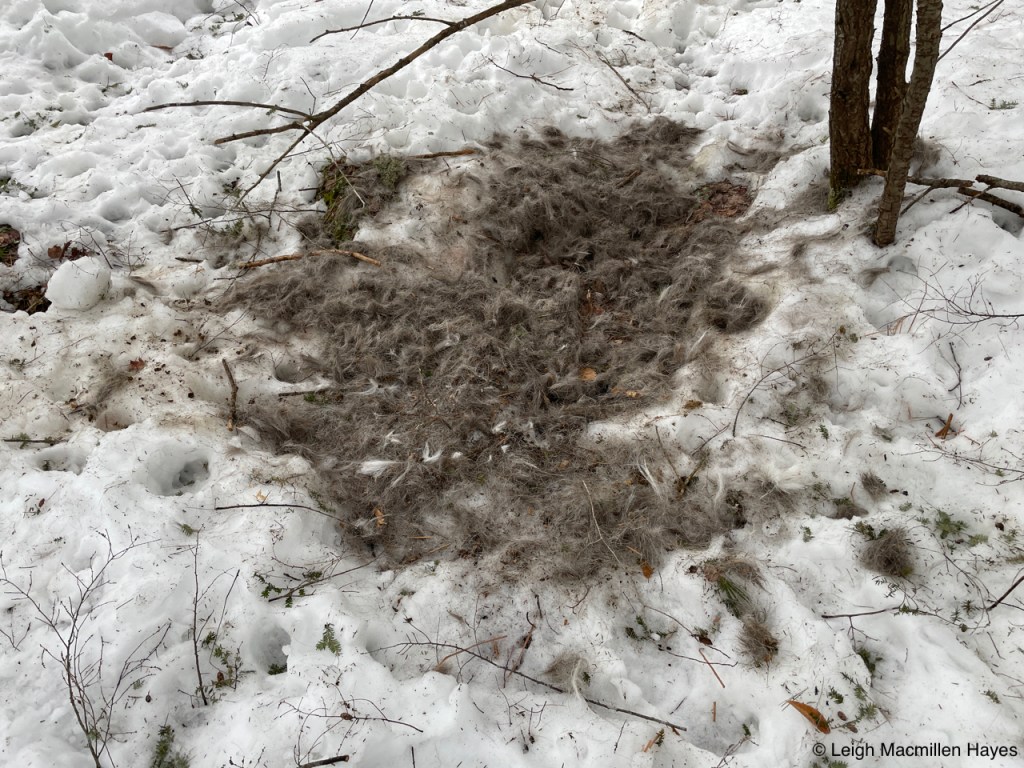

One of my favorite things about the Durgin cellar hole is the cold storage. In the cold to come, it will still serve as storage, so witnessed by the findings within today.

For the back corner has long provided protection from the elements for a porcupine, given the scat pile.

Because we were there, we decided to check on the Durgins who hang out a ways in the woods behind their former home and followed a stonewall to their locale.

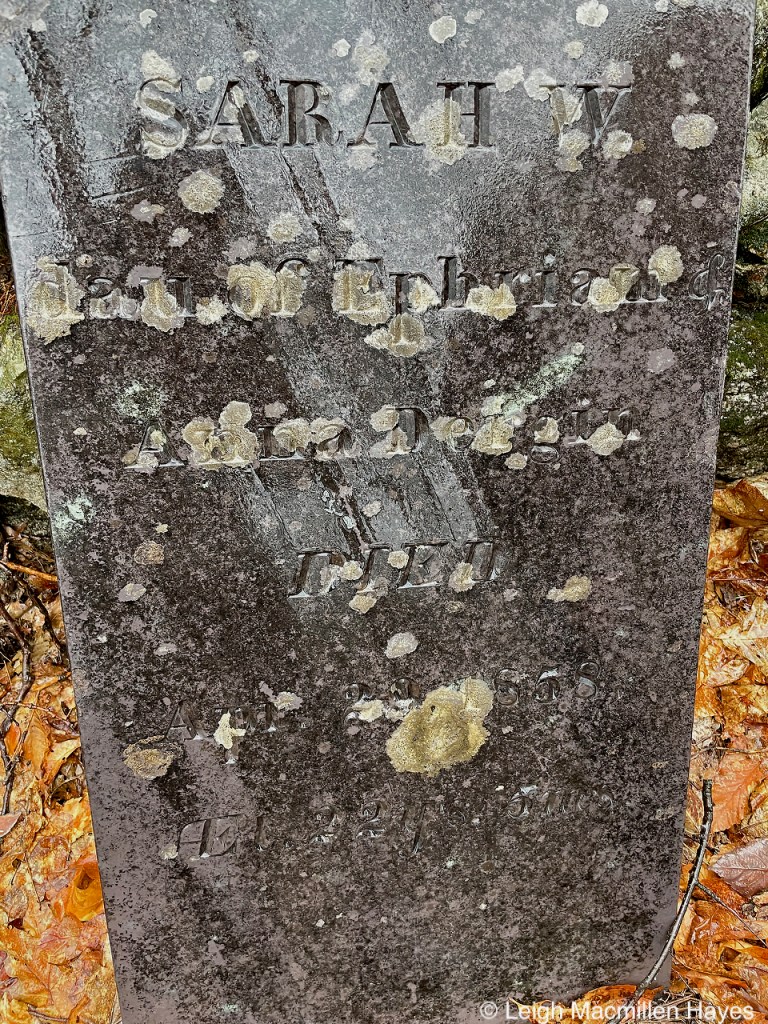

Three of them were still there. Sarah, daughter of Anna and Ephraim (E. Durgin on the map), died in 1858 at age 22.

Beside her stood Mary, wife of Sumner Dergin, who died before Sarah in 1856, also at age 22.

Our best guess is that Sarah and Sumner were siblings.

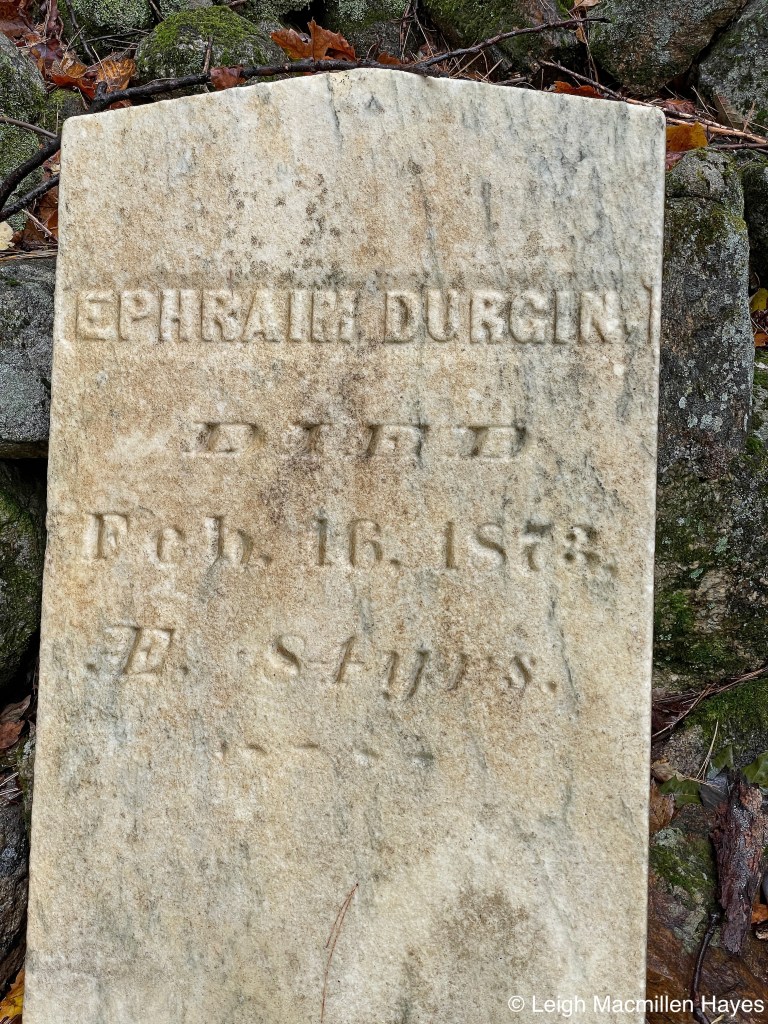

Ephraim, father of Sarah and Sumner, and husband of Anna, died in 1873 at age 81. Did you notice the difference in stone from the 1850s to 1870s? Slate to cement. And the name change–Dergin vs. Durgin. We’ve learned through geneology research that spellings often differ. I found the following a few years back on RootsWeb.

8. ANNA3 FURLONG (PATRICK2, JOHN1) was born 1791 in Limerick, Maine, and died 1873 in Stoneham, Maine. She married EPHRAIM DURGIN June 18, 1817 in Limerick, Maine14. He was born April 13, 1790 in Limerick, Maine, and died in Stoneham.

Children of ANNA FURLONG and EPHRAIM DURGIN are:

i.OLIVE4 DURGIN, b. 1811, Stoneham, Maine; m. DUNCAN M. ROSS, April 11, 1860, Portland, Maine.

ii.SALOMA DURGIN, b. 1813.

iii.ELIZABETH DURGIN, b. 1815.

iv.SALLY DURGIN, b. 1817.

v.SUMNER F. DURGIN, b. 1819, Of Stoneham, Massachusettes; m. MARY ANN DURGAN, July 11, 1853, York County, Maine; b. Of Parsonsfield, Maine.

vi.CASANDIA DURGIN, b. 1821.

vii.EPHRAIM DURGIN, b. 1823.

viii.FANNY DURGIN, b. 1825.

Sarah isn’t listed above. But . . . Sally and Sarah were often interchangeable.

We ate lunch with the family as we looked out at the view they enjoy every day–possibly once called Durgin Hill, and then maybe Sugar Hill.

After lunch, our journey continued a wee bit further until another witness stopped me in my hiking boots. It took me three bear hugs with arms fully outstretched to completely circle this ancient Sugar Maple. Can you imagine the tales stored inside this great, great, great grandfather?

And at his feet, a wee one to appreciate –a Many-fruited Pelt Lichen, the many fruits being the brown fruiting bodies or apothecia.

A few steps away, we reached the Willard family foundation. Two large granite slabs are visible in the back and I had to wonder if they originally formed the roof of another cold storage.

Again, I referred to Jinnie Mae’s research. By 1880, the Willards house was occupied by the McKeens. And the Durgins were no longer living there, which makes sense given that Anna and Ephraim both died in 1873. The Rowlands had moved in to their home.

A newer member of the neighborhood, a Striped Maple, may not have known any of these occupants, but despite the full canopy of evergreens and maples and birches, it sure knew how to produce large leaves to increase its chances of survival.

Eventually, we turned west and followed an old road way bordered by stonewalls on either side. I remember when few trees grew there, but now one has to move through like a ball in a pinball machine, ricocheting off this tree and that rock along the way.

It’s well worth the effort because it leads directly to Willard Brook, which flows southward toward Great Brook , where we first began our journey.

Though I know the first part of the trip well, I sometimes get a bit mixed up with the second part and such was the case today. That said, as we scrambled up and down the sometimes steep hillside beside the brook, we came upon these wheels and bingo. We knew them as old friends we’d met on a previous trip.

There is so much history tucked away in these woods, and I gave thanks for two more witnesses, who despite their differences, stood together and supported each other.

We live in unceded Wabanaki land and I’ve come to some understanding of the Native American presence that once existed here in this place between Great Brook and Willard Brook. And I’m sure still does.

After witnessing the past, we walked back down the road as raindrops fell. A perfect hush to end the journey.