It didn’t start out that way for me. Loving bugs, that is. I thought they were just that . . . bugs. Bothersome. Biting. Stinging. Needing-to-be-swatted critters.

And then one day that all changed for me as I began to take a closer look. And since the past two weeks a friend and I shared our keen interest in these critters during two Senior College (Lifelong Learning) classes, I thought I’d bring some of it alive again in this space.

If you attended these classes, there will be some repeated information, but it’s not all here, or we’d need four hours! And I’ve added a few things that I didn’t have time to include in class.

Enough said. Let’s get started.

Most, but not all, insects have mouth parts, but they come in a variety of forms. The most basic are for chewing, but sponging, siphoning or sucking, and piercing, then sucking are also important. Mosquitoes, adult fleas, lice, and some flies puncture tissue with a slender beak or proboscis, and suck the fluids within. Butterflies, moths, and bees also dine on fluids, but the proboscis of these species lack the piercing adaptations and extend only when their feet touch and “taste” a sweet solution. A spongy tip, aka labellum, on the tip of the proboscis allows most flies to sop up liquids or easily soluble food. Other insects, like ants, grasshoppers, beetles, and caterpillars nibble and grind their food with jaws or mandibles, which move horizontally.

Think mosquito: sticking a straw into a juice box (through your skin) and then sucking; bee and butterfly: using a straw; fly: adding a sponge to the tip of the straw; caterpillar: using pliers horizontally. You get the picture?

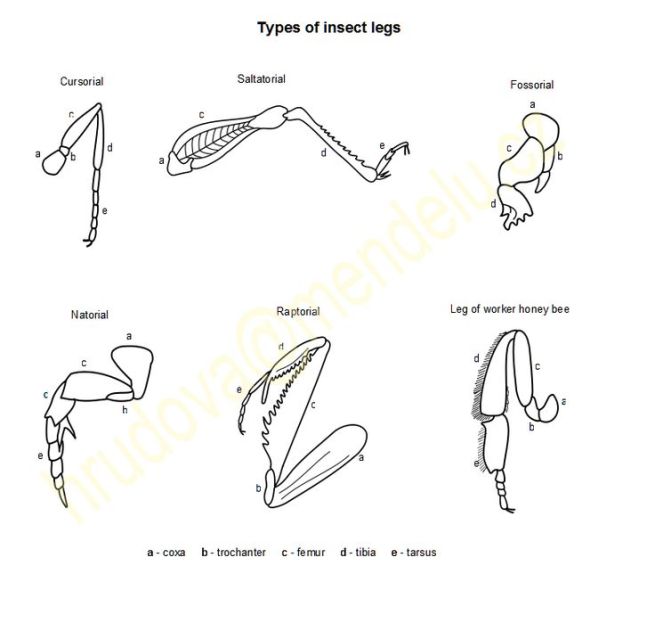

And then there are the legs and feet. Because insects live in a wide range of habitats, there are a wide range of structures to get the job done.

Cursorial: (running) Insects like Tiger Beetles, who have long and narrow legs and move swiftly (even when canoodling, though they do slow down a wee bit).

Saltatorial: (jumping legs) In this case, it’s the hind legs of Grasshoppers that are filled with bulky strong muscles to help propel them forward that come to mind.

Fossorial: (Digging) These insects, such as Dog-day Cicadas, live underground for the first few years of their lives and need their legs and feet, which look like modified claws, to dig. They tend to be broad, flat, and dense.

Natatorial: (Swimming) Aquatic beetles and bugs can move swiftly through water.

Raptorial: (Hunting) Enlarged with powerful muscles, these are found at the front of the insect where they are ready to strike at any time, then grab and hold prey, such as a Robber Fly has.

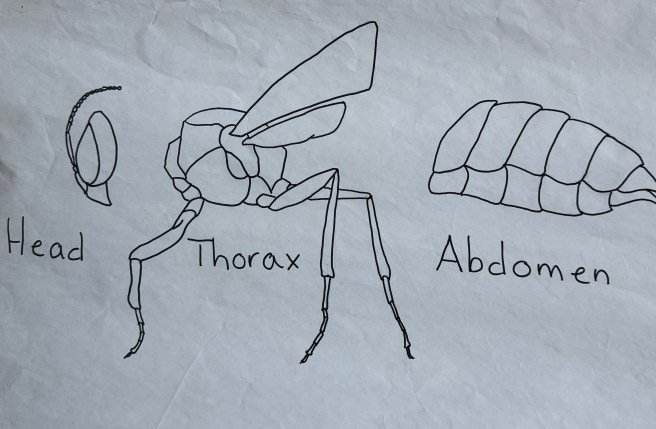

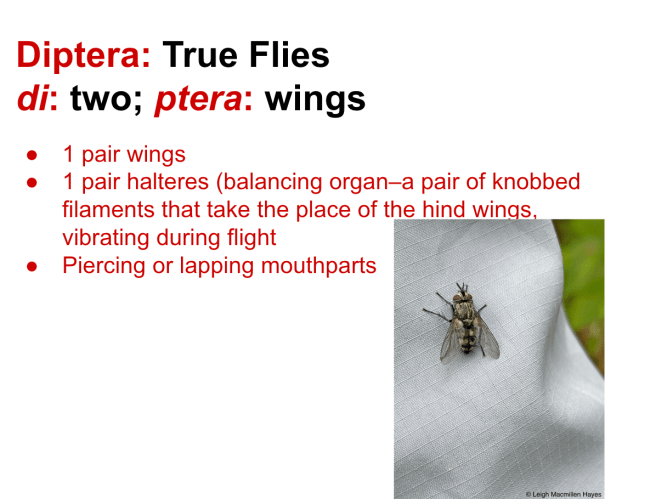

And just a reminder from science class all those years ago, without going into all of the details, like the fact that there are three sections in the thorax, the head contains the eyes, proboscis, and antennae, thorax supports three pairs of legs, and wings (and halteres or modified wings shaped more like clubs that help with balance and steering when in flight), and an abdomen.

I could share tons of photos of Bumblebees (and I’ve found it written as one word, and two), but this is one of my favorites because it shows the insect’s RED tongue seeking nectar from the Goldenrod.

This is another favorite because I sometimes forget that despite the rain, the insects are still out there during the summer, and perhaps finding the right spot to avoid getting wet comes with age.

Bumblebees are very hairy. They build underground nests and I have to wonder why this one didn’t return to hers, but perhaps the rain came down suddenly. It did rain a lot last summer.

In the spring, the queen who overwintered, conducts a reconnaissance mission in search of a good nest site and you might spot one in a weaving flight close to the ground as she checks out every little hole that might serve as the right underground chamber for her brood.

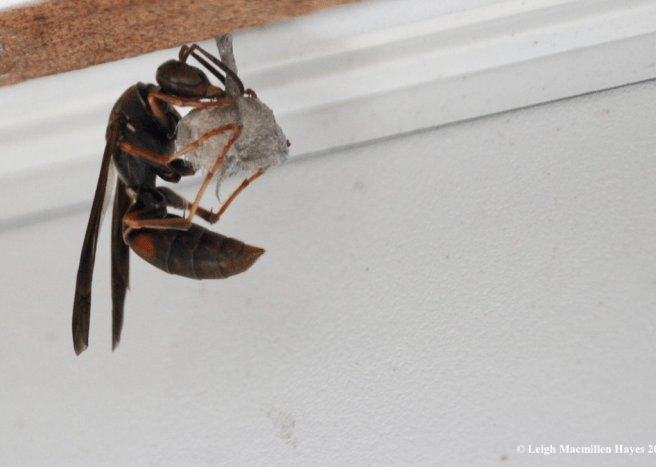

Paper Wasps are easy to identify because unlike other wasps and bees, they hold their wings out to each side rather than folded over the back. The fertilized queen also overwinters behind tree bark or under leaves.

So this wasp decided that a door jam in our house was the right spot to place a nest. Heck. It was protected. Out of the weather. Warm. All the comforts of home.

To build such a nest, fiber is gathered and chewed from buildings and trees and fence posts and then mixed with saliva until it becomes a papery substance.

The hexagonal cells created face downward and tada, a nursery is formed, each cell supporting one egg.

I am probably one of the few people in the world who spent several days standing on a kitchen chair to get a series of photos as this nest was being built.

And I was successful in my efforts, that is, until My Guy discovered it and decided that it really wasn’t such a good idea to have a nest in the house. I guess it speaks to how well the door didn’t fit into the door jam. We’ve since completed a reconstruction project of our own, so sadly, this won’t occur again, but never fear, there are usually lots of nests around the outside of the house.

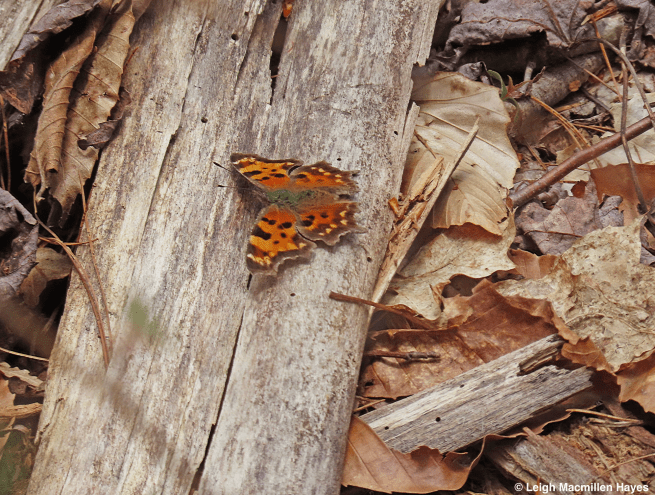

Another who overwinters behind bark as an adult is the Mourning Cloak Butterfly, so named because the coloration is supposed to remind us of a cloak one might wear while mourning the loss of a loved one.

One activity that butterflies engage in, and usually it’s the males who do this, is “puddling.” We think of butterflies as flitting from flower to flower, sipping nectar here and there.

BUT . . . they need more. Yes, flower nectar is good for energy, but when your mind is on something else, you want to supplement your diet. Sugar water won’t give you that something extra to produce viable offspring.

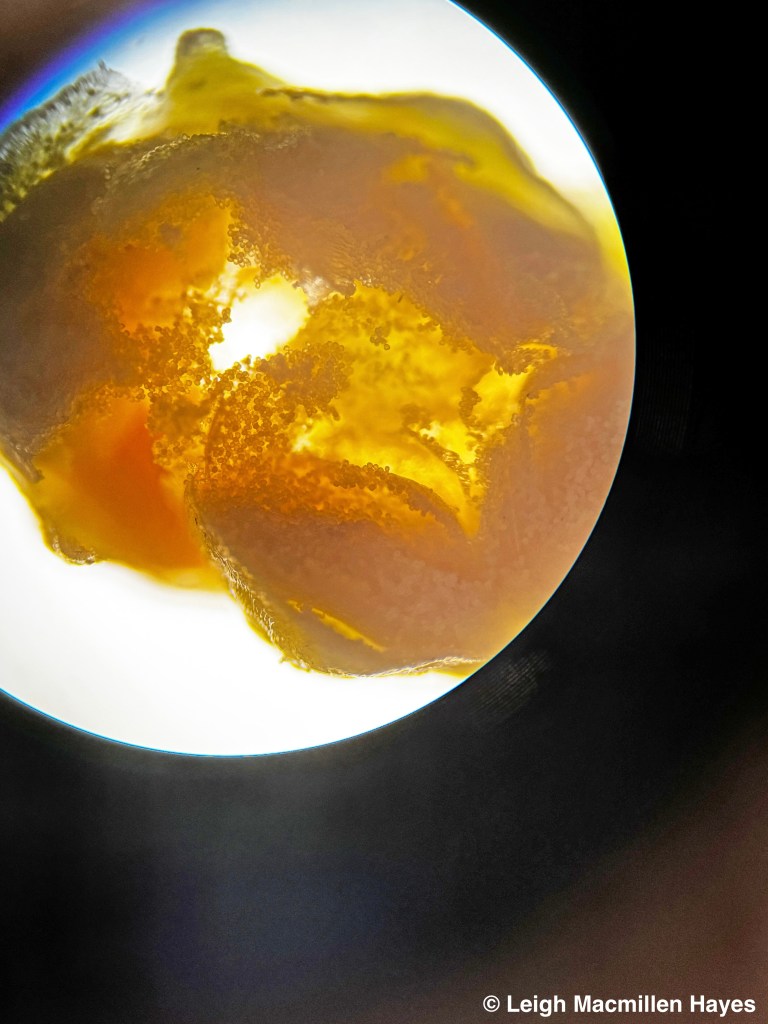

Puddling means injesting salts, minerals, and amino acids from mud, scat, fermenting fruit, or carrion. In this case, the Tiger Swallowtails are seeking these treats from a squished frog. When they get around to canoodling with a mate, they’ll pass along a wedding present via their spermatophore, which will give their brides an extra boost and the females will pass that on to the eggs, thus giving them a higher chance of success.

For me, it’s the last two items in the list that help me best differentiate between butterflies and moths.

Notice the feathery antennae of the Luna Moth, who by the way, has no mouth parts because as an adult the job is only to mate. Leave the eating to the caterpillars in their larval form.

It’s just the opposite for the Clearwing Hummingbird Moth, who has a long proboscis like a butterfly that extends into the flowers to seek nectar. When in flight, the proboscis curls up and is tucked to the side of the moth’s head.

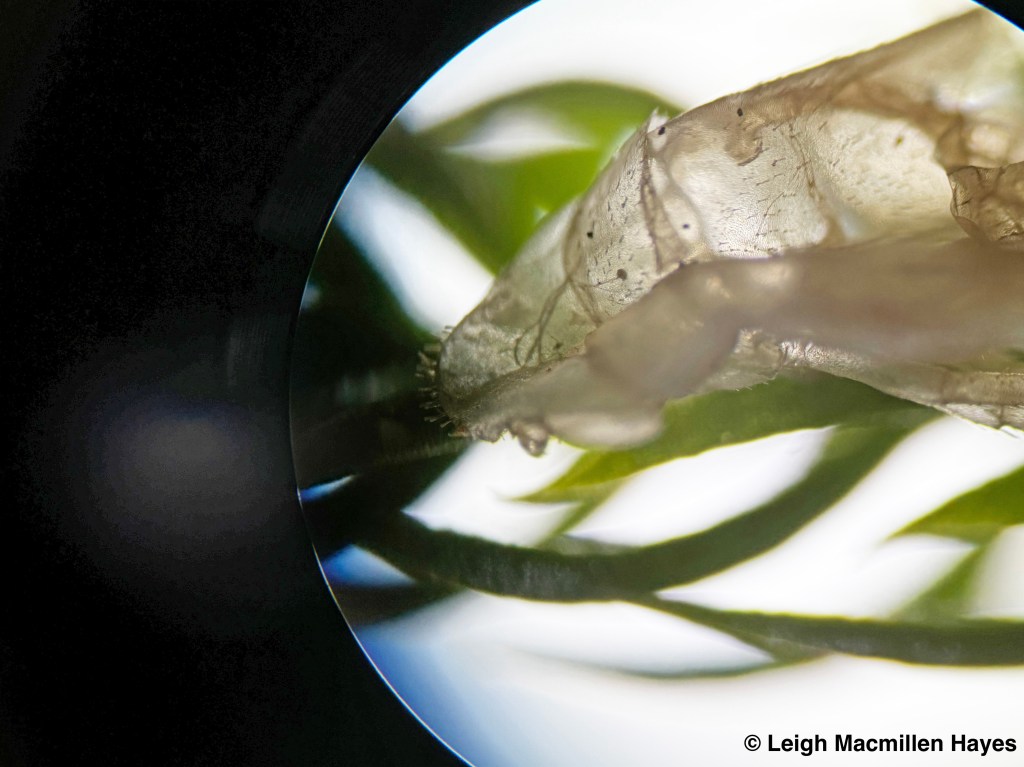

Grasshoppers molt as they grow and this was a larval form I spotted one extremely cold and blustery March day. It hasn’t any wings yet, but those will come as it sheds its skin several times before reaching adult size. Still, the youngsters look very much like their future mature selves.

And to round things out, I found this molted skin in the fall and was totally intrigued by how much detail it included, right down to the spars on the hind legs. Of course, they should be there, but I was totally surprised because I hadn’t thought about it before.

My next friend is a “Where’s Waldo” feature because it blends into its surroundings so well. Curiously, I grew up with the ever present summer song of Katydids in Southern New England, but despite living in the North Country for all of my adult life, I haven’t heard one in years. Then again, I only see one or two a summer it seems, so maybe there aren’t too many around who will listen.

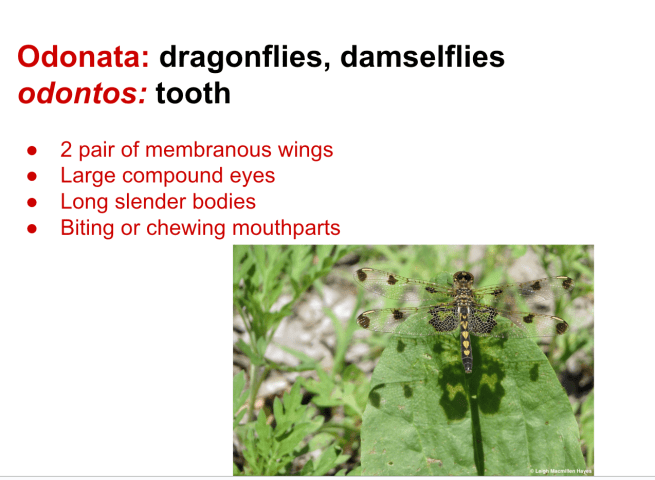

Both dragonflies and damselflies begin life as aquatic insects. Think natatorial legs.

As some of you know, I could share a million photos of dragonflies and I’d never get tired of it, though you might. I am limiting myself to just a couple, including this female Racket-tailed Emerald, so named for the abdomen that widens toward the end somewhat like a tennis racket. I love imagination!

But probably my favorite dragonfly is the Stream Cruiser, especially when it has newly emerged and presents in browns and whites that make me think of Oreo cookies or a no-bake Icebox Cake (which I was honored with for my birthday this past year–thanks Deb!)

Just like there are subtle differences between butterflies and moths, the same is true for dragons and damsels.

I often meet members of this Orange Bluet family of damselflies when I’m paddling near our camp. My only wish is that this one had gone for the meal that awaited–a Deer Fly; before I became the Deer Fly’s meal. It wasn’t my lucky day.

The Orange Bluet is a pond damsel, so called because its wings are clear and closed when it perches.

Among the damelflies, there are also broad-winged varieties, such as this female Ebony Jewelwing. If you are near a stream or damp spot in the woods, be on the lookout for these beauties. And note the white stigmas on her wings. Her guy’s wings are all black.

And one last damsel that I wanted to include is a member of the spread-wings. It’s easy to think of these as dragonflies because the wings are . . . spread a bit apart like the dragons. But . . . note the thin body. And the arrangement of the eyes. Damsel eyes are a bit like barbells.

Beetles come in so many shapes and sizes and colors. And their antennae are variable as well. I just love the antennae on this Oriental Beetle.

There are also a variety of long-horned (long antennae) beetles, but what caught my eye was that these two were totally undisturbed by an ant that was seeking nectar as they romped.

Because I stalk my “gardens” and the adjacent field, I happen to know that these two canoodled for hours. I did miss their point of departure, but can safely assume I’ll meet their children in the future.

My final beetle to share today is the Winter Firefly, who is fireless as an adult. Though I’ve never seen this, I’ve read that the Winter Fireflies eggs, larvae, and pupae glow. But not the adult.

Though visible all year, now is a fun time to locate these beetles. (Wait–it’s a fire”fly,” but not a fly? Nope! And if you call it a Lightning Bug, which are its close relatives, you should note that it’s also not a bug!)

Notice the pink parentheses bracketing the shield behind its head–as a former English teacher, that makes my heart sing.

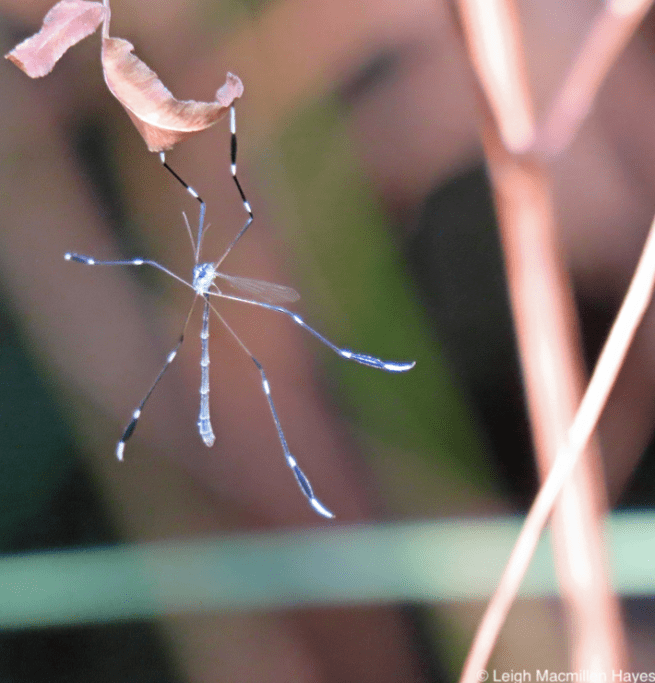

One of the most mysterious true flies in my neck of the woods is the Phantom Crane Fly. Think Phantom of the Opera when you look at the coloration. And seriously, this crane fly literally floats through the air, looking like the small outline of a box if you are lucky enough to spot it.

Crane flies are not oversized mosquitoes and they will not harm you.

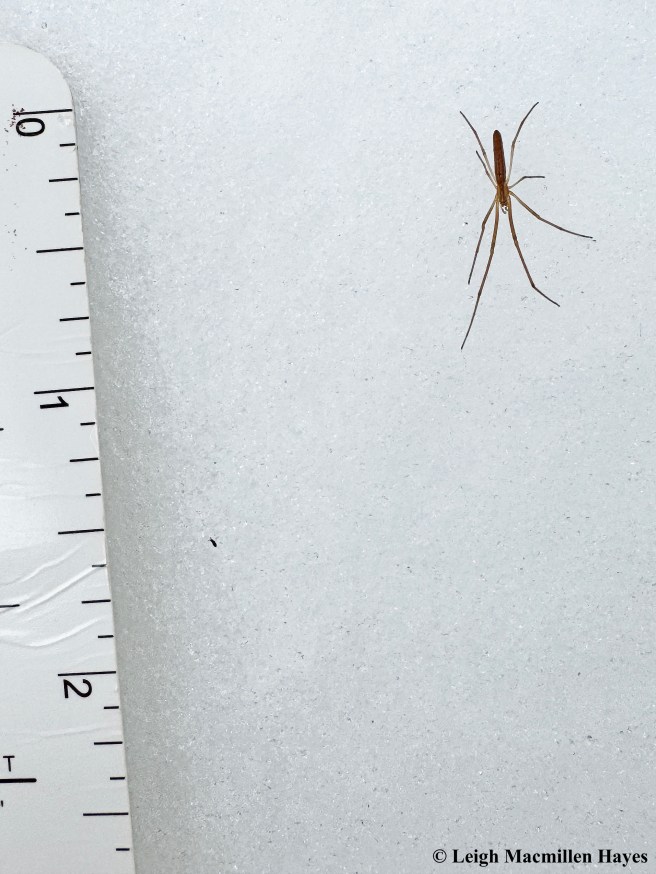

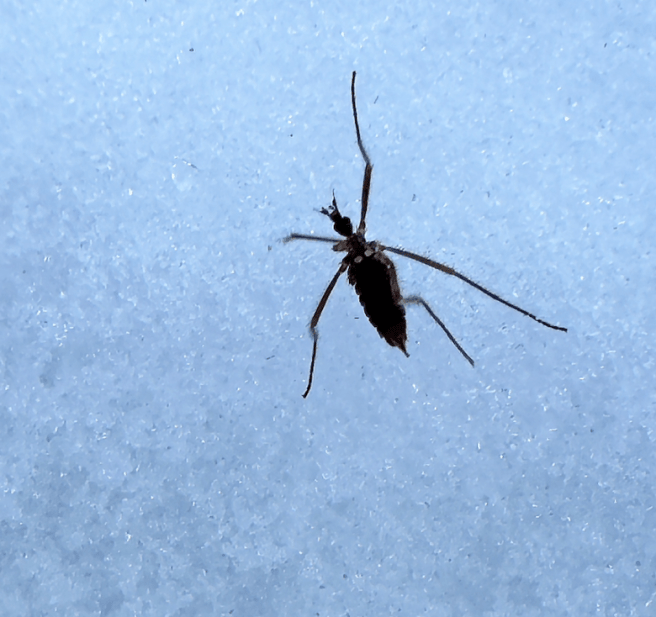

Another in the Crane Fly family is the Winter Cranefly, a tiny, mosquito-looking insect with super long legs. The lightbulb is two inches long, so that should give you a bit of perspective on this insect’s size.

Like all members of the family, these can be found in moist places. And the males form swarms in an effort to perform pre-canoodle dances to entice a mate.

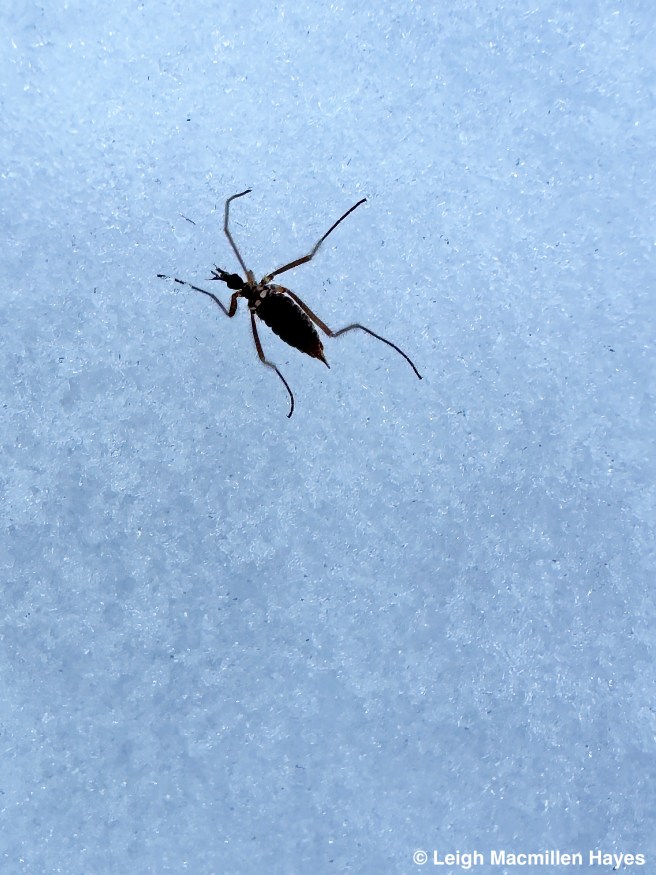

Another who is closely related to the crane fly family is also most readily seen on snow, this being the Snow Fly. It differs from other crane flies, however, in that it is wingless.

When I first spotted this one about a month ago, on a frigid day, I thought it was a spider at first. Until I counted its legs. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Yikes. Certainly not the eight legs of a spider. But . . . where’s leg #6?

Snow Flies, I learned, have the ability to self-amputate a limb that is beginning to freeze as a way to stop icy crystallization from spreading to the rest of the body, and especially its organs.

Since that first sighting, I’ve spotted a few more, and thankfully, all feature complete sets of three pairs of legs.

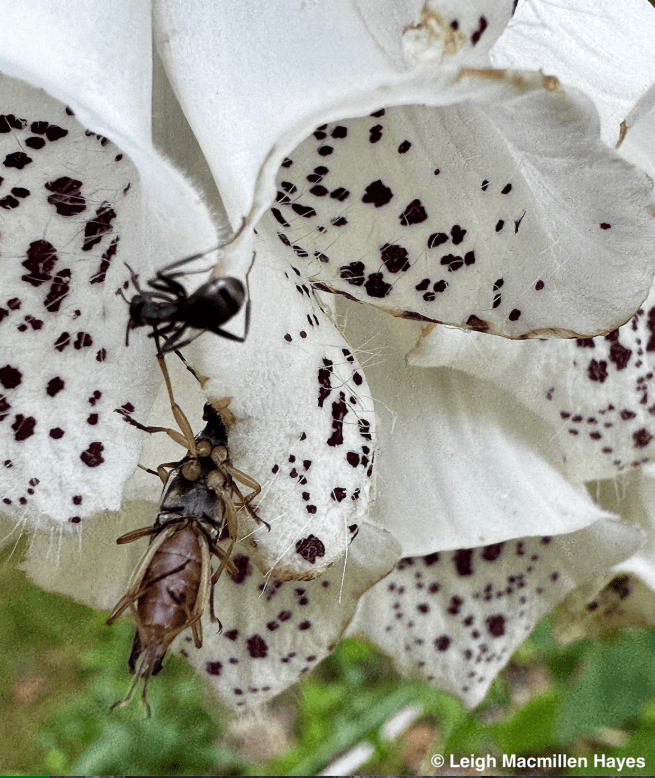

Next up in today’s lesson plan, the Robber Fly. This particular species has such a hairy body that it mimics a bee. Its proboscis, or mouthpart, is rather beak-like, the easier to consume insects.

Robber Flies wait patiently, or so it seems, and then when the time is right, they pounce. And stab the prey with their straw-like mouthparts, injecting the subject with enzymes that paralyze it before sucking the liquified guts. Yum.

While I found the Bumblebee hanging out on a rainy day, it was a humid day when I spotted this Robber Fly taking advantage of a little shade. And perhaps actually awaiting a meal that might fly or crawl into the plant.

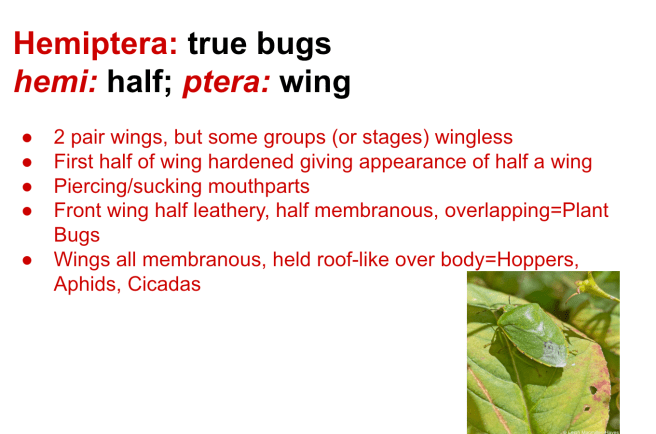

The final order of the day encompasses the True Bugs. Most True Bugs suck juices from plants. Including this wooly aphid that looks like a snowflake when in flight.

It’s the white fluff covering their body that is their defining characteristic. The fluff is made of small waxy fibers that serve to help keep the aphids hydrated. The hairs may also deter predators from ingesting them.

Sap-suckers though they may be, they don’t harm their host plants, and are a delight to spot in flight–much like little fairies flying about the woods.

Another sap-sucking insect is another one of my favs: the Dog-day Cicada, this one being the cast skin of a nymph. I could wax poetic about them, but you can read more by visiting Celebrating Cemetery Cicadas, Resurrection, Consumed by Cicadas, My Love Affair, to name a few. I guess I really do like them since I’ve written about them so many times.

Love bugs yet? If not, I hope you at least will take some time to appreciate them. In winter and summer. And spring and fall.

Of all my favs, and there are many it turns out, this one pictured above probably tops the list. It is, after all, chocolate! Under those leathery elytra wings, of course. My friend, Aurora, gave this to me a year ago, and I don’t think she realizes how much I really love it and that it sits in a shady alcove on my desk so it doesn’t melt. Bugs should not melt! Nor should they be eaten! Especially Love Bugs!