I’ve been lamenting the lack of snow. That is, until I head out the door, don microspikes over my winter boots, and slow my brain down. And then . . . the winter world pulls me in.

It’s amazing what stories there are to interpret, whether in a dusting or a few inches of snow. But first, I need to think about the overall picture and consider where I am.

What state am I in? Maine

What season is it? Winter (my favorite)

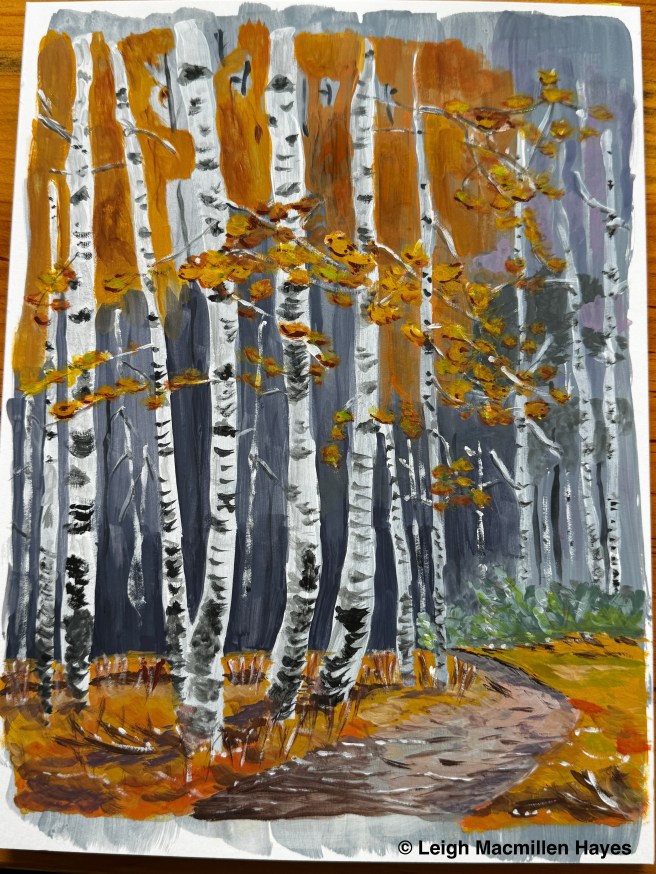

What type of forest? Ah, that’s always changing and this week saw a range, for sure. Sometimes it’s coniferous.

Other days, deciduous.

But also a mixed forest.

Or beside a frozen wetland.

Or even a wetland with some open water.

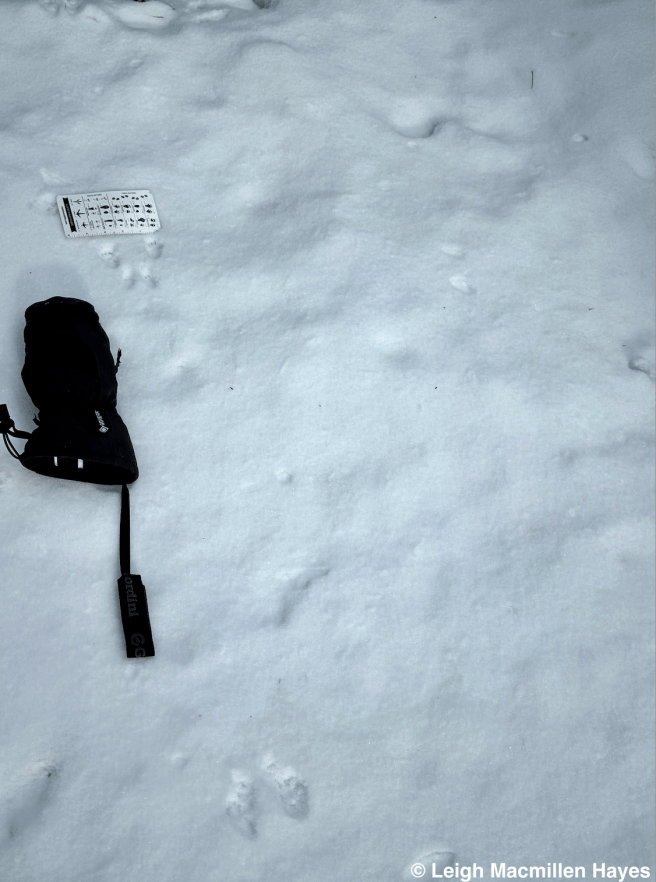

When I do encounter tracks, I have to think–how is the mammal moving through the landscape? In more or less a straight line with a bit of a zigzag to it?

And if so, is it just one mammal, or more than one?

I need to look at the overall pattern, which might mean backtracking a bit (don’t want to put pressure on the mammal, especially if the tracks are fresh).

The thing is that the tracks in the three above photos were made by three different critters, all of whom often move in the same pattern–straight line with a bit of a zigzag as I already said. The left front foot lands and packs the snow, and as the animal moves forward, the left hind foot lands where that front foot was, and visa versa on the other side. So what is actually a set of two prints, one directly or almost directly on top of the other, looks like one print from our point of view. The front foot pre-packs the snow and the hind foot lands in the same spot to make it easier for the mammal to move more efficiently, especially since he doesn’t have a warm fire and dog food awaiting him after a walk in the woods.

“Who created them?” you ask, because of course, I can hear you wondering. The first with my foot beside the prints: Red Fox; second: Eastern Coyote; third: Bobcat.

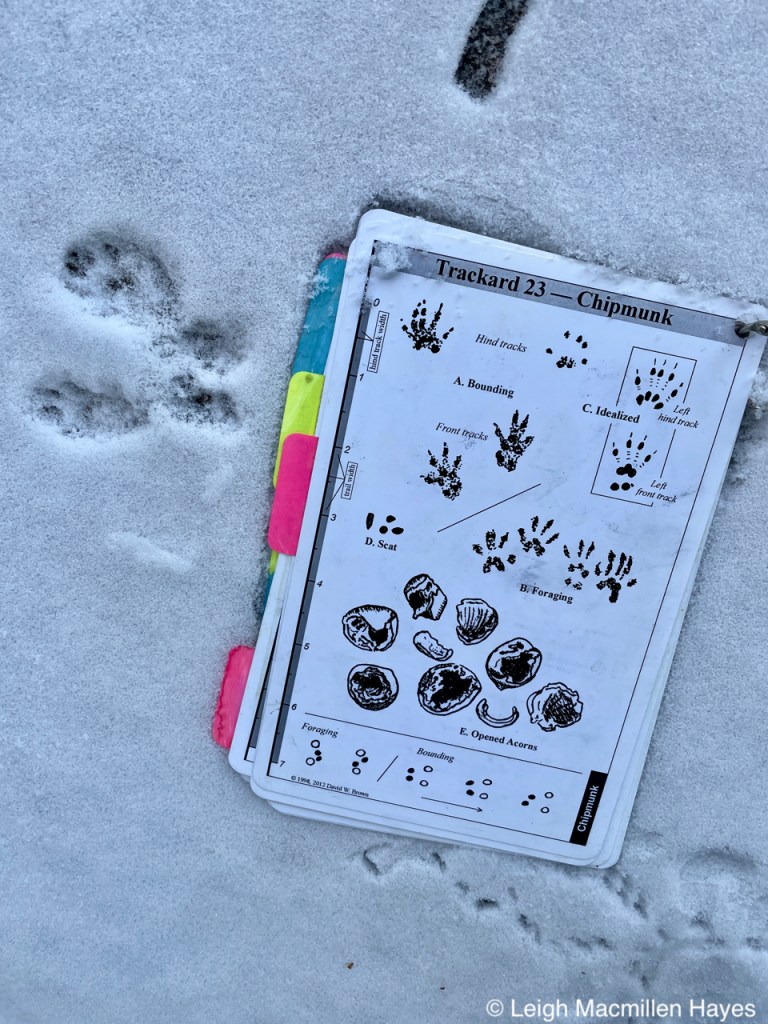

Briefly, I want to share other forms of movement that we might spot in the woods. These are groups of four prints left behind by a leaper/hopper. Several critters move this way and the best way my brain can tell them apart is by the straddle or trail width–measuring from the outside of one of the larger prints to the outside of the other.

Just to clarify, what you are looking at in one group of four, two smaller prints are the front prints, which land first. The hind feet swing a bit forward just before the front feet lift off and so the hind feet appear to be in front of the front feet.

“What?” Yup. Thus, this mammal is moving toward the top left of the photo, because the hind feet always appear in front of the front feet. Have I lost you yet?

Together, they look sorta like a set of two exclamation points. In deeper snow, they can also look like double diamonds, or even Batman’s mask.

My game camera recently caught a Gray Squirrel in this motion, and if you look closely, you can see the back feet swinging around in front of the front feet.

What is the trail width or straddle for a Gray Squirrel? 4+ inches

Red Squirrel? 3+ inches

Chipmunk (who does come out occasionally in the winter)? 2+ inches.

Another leaper/hopper also leaves a set of four prints, but usually (not always) the two front feet are not parallel like the squirrels. This mammal is hopping toward the lower right hand corner, with the hind feet being out in front to indicate direction.

If you take that photograph and flip it 180˚ so that the world appears upside down, cuze sometimes it just does, you may see what I see that helps me with a quick ID: a snow lobster: the two hind feet out in front, being the claws and the two staggered front feet behind forming the tail.

“And the creator of the snow lobster?” you ask.

Snowshoe Hare.

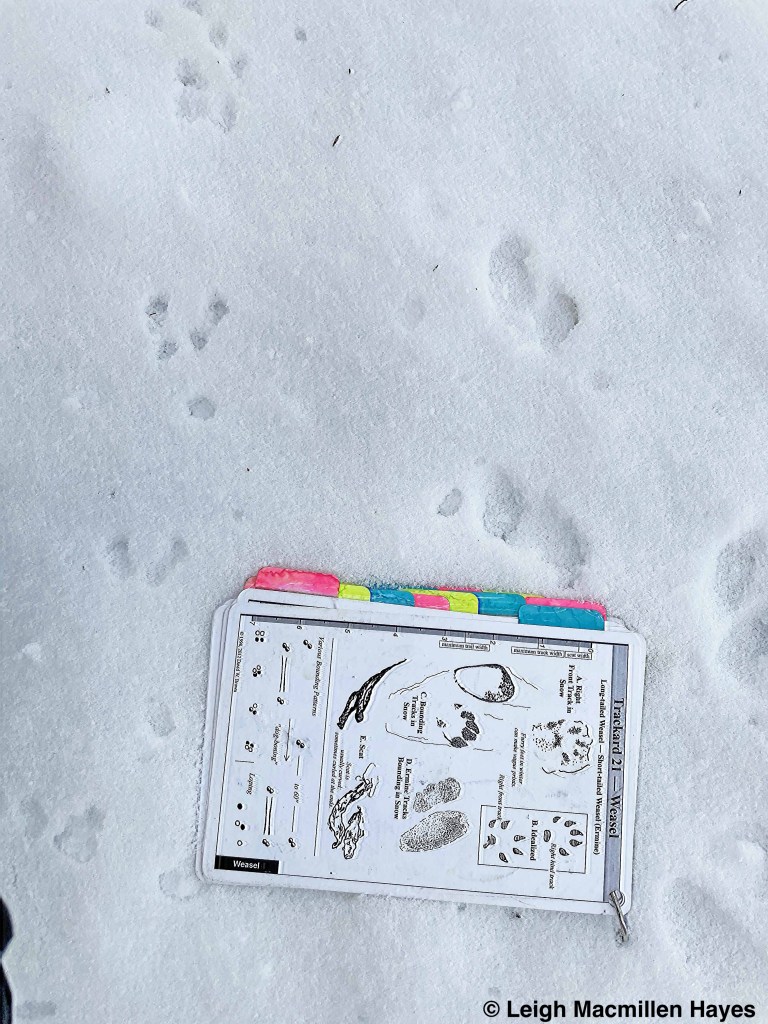

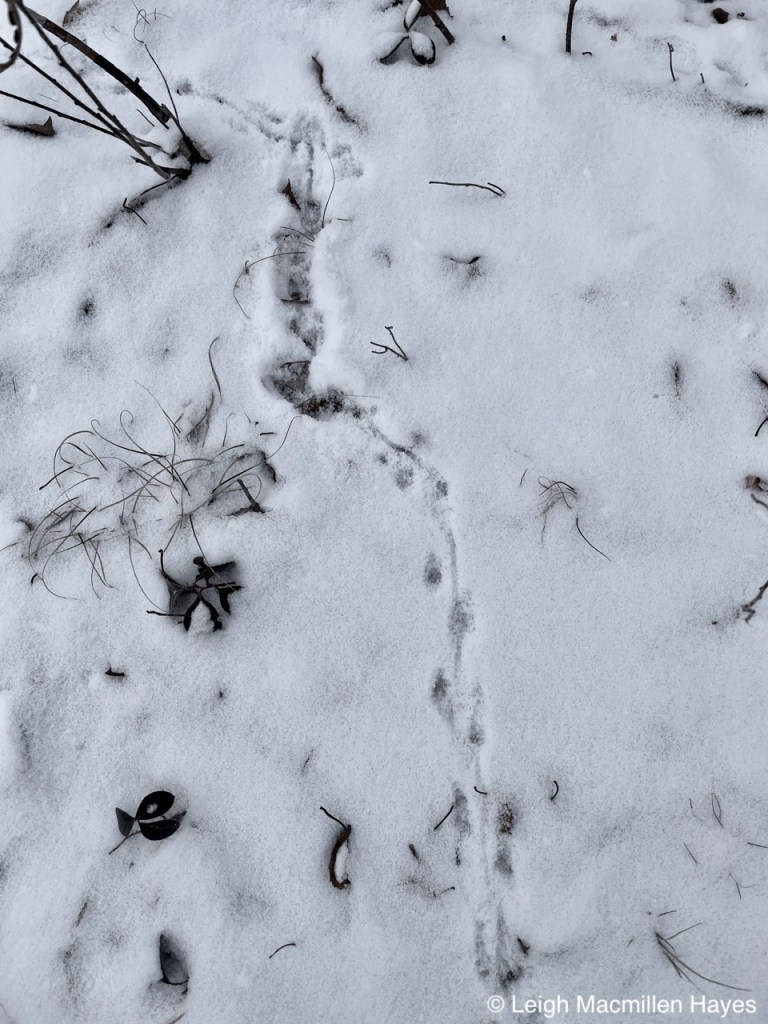

Just when you think you are getting it, a wee critter enters the scene because, well, it’s everyone’s favorite food (for those who are predators that is), and I have a hunch you’ll spot these tracks rather often.

First, the wee one moves in the direct registration (zigzaggy straight line) gait of the coyote, foxes, and bobcat.

But then it changes things up and may even start tunneling as it leaps forward. And in deeper snow, you’ll see a hole beside vegetation and know that it ducked under to try to avoid becoming a meal.

These are the tracks of a Meadow Vole.

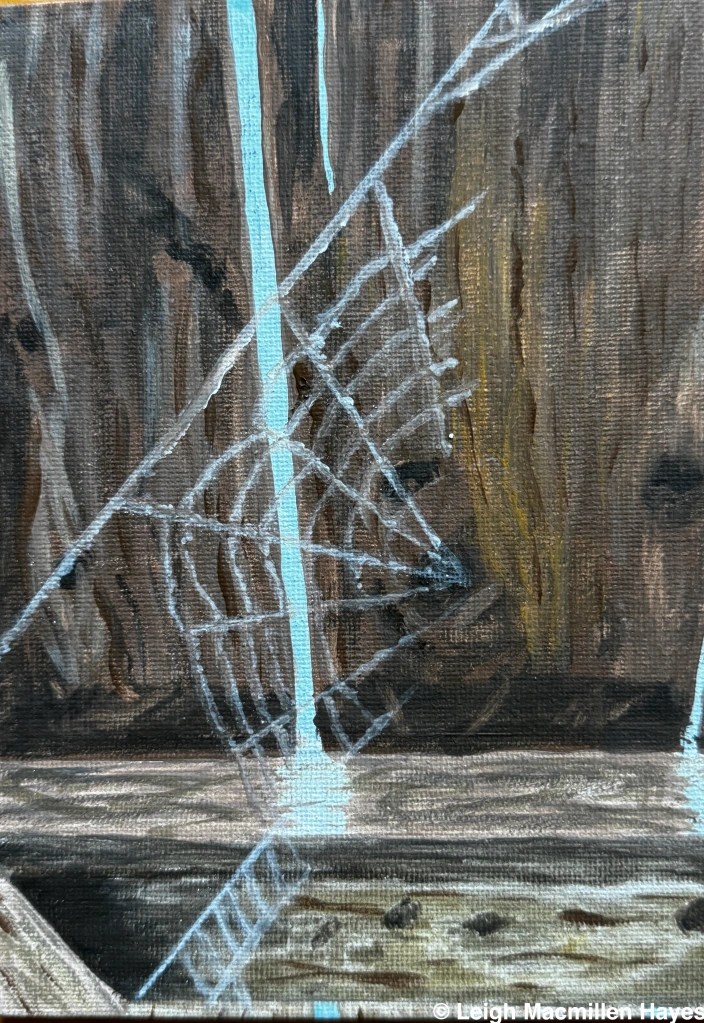

There is a group of mammals who are bounders, so much so that their bodies move almost like accordions, and as the hind feet push off, the front feet land on a diagonal, and the hind feet follow suit and land where the front feet had been, while the front feet are airborne once again.

Do you see the diagonal pattern of the impressions. For the most part, they move on the same diagonal for a while, and then might change it up.

It’s the weasel family that leaves this pattern, and these are from a Mink. Long-tailed weasels and Ermines leave even smaller prints.

Fisher prints are larger and they sometimes change their gait a bit, but always you can find evidence of the diagonal in the middle of pattern; and Otters LOVE to slide.

Finally, in this discussion of patterns, there are the waddlers, those critters with wide bodies (Think Beaver, Porcupine, Raccoon, Black Bear). Their forward motion varies, but this is one of my favorites: the sashay of the pigeon-toed Porcupine.

Another waddler, or wide-hipped critter is the Raccoon. It’s feet look a bit like baby hand prints. But a key (pun intended) characteristic is the switch of the diagonal when looking at how this critter moves through the woods.

Now that you’ve thought about the surroundings and looked at the mammal’s gait, it’s time to consider the size and shape of the print, count toes that are visible, look for nails, examine the overall track and prints from different angles, and take measurements.

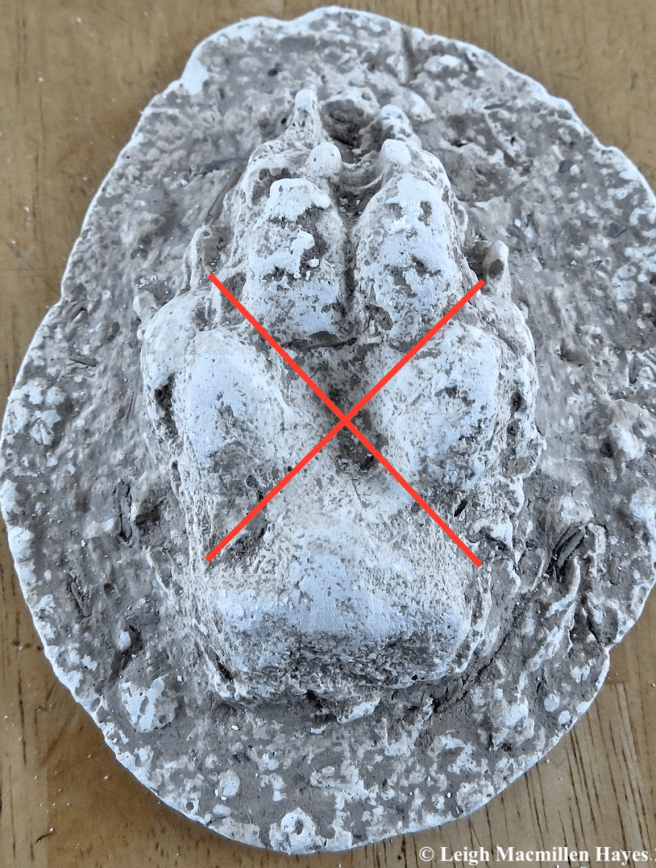

We often talk about the X ridge between the toe pads and metacarpal pad of the canines. But sometimes people have a difficult time seeing it, so I find outlining it may help.

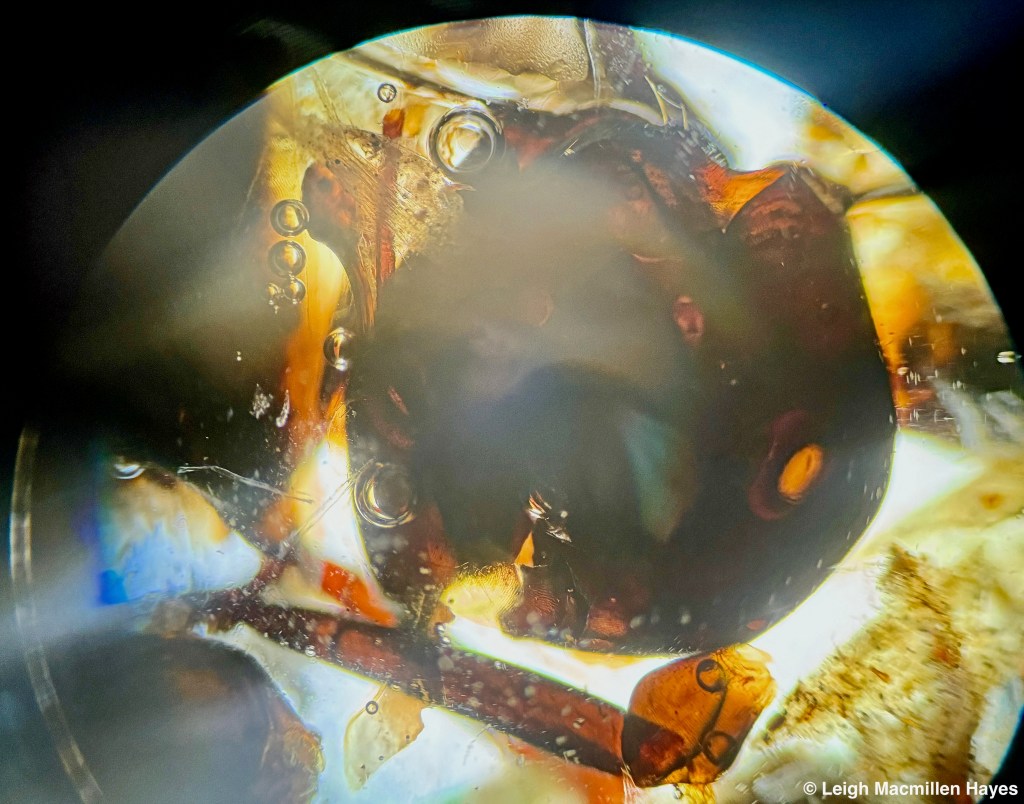

Think about this cast of a Coyote print: In your mind’s eye, flip it over so that the oval shape is actually at ground level, and the prints, that were in the mud were below the oval. If you look closely, you’ll realize you are looking at two impressions. The smaller one on top, would have been at the bottom of the impression as one foot landed. And then the second foot landed almost directly on top of it.

“Wowza,” you exclaim.

And notice the toe nails–how they are rather close together and not splayed like your fur baby’s nails when you go out to play in the snow. Conserving heat. Brilliant.

Here’s a look at what you might see when you spot an actual Coyote print.

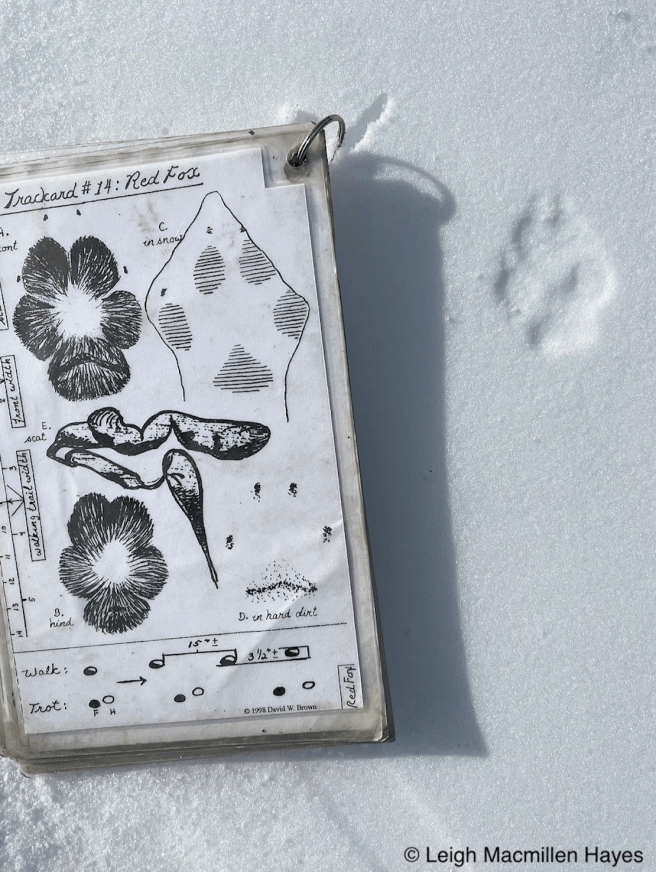

Another with the X that I didn’t outline, but I hope you can see, is the impression of a Red Fox print. I made this one with an actual Fox foot courtesy of the Maine Master Naturalist Program (and Dorcas Miller). What I love is that you can see the chevron that appears in the metacarpal pad of the fox’s foot .

Sometimes I can see the chevron, sometimes I can’t. It’s all about snow conditions. Some days are perfect for tracking and others are a challenge. But I’ve said a hundred times, when I’m alone, I’m 100% correct in my ID.

To differentiate the walkers/trotters, there’s one more letter to consider, this one being closer to the beginning of the alphabet: C. And it indicates a Bobcat. C is for Cat. Another thing to think about when looking at the zigzaggy straightline, are the toes symmetrical or is there a lead toe?

Symmetrical: Coyote and Foxes. They are also more oval shaped; or kinda like an ice cream cone with one small scoop on top.

Lead toe: Bobcat. Round shape, about the size of a fifty cent piece, while your cat is a quarter.

I’ve been seeing lots of Bobcat prints and tracks this winter. And Snowshoe Hare. Hmmm.

Okay, so enough for the lecture. I want to show you what else I’ve seen in the past week, cuze part of the fun is interpreting the stories.

Last weekend, in the midst of a snowstorm, I taught a tracking lesson for this year’s Maine Master Naturalist class. One of the activities, that also served as an icebreaker for the students, was that within their mentee groups, they were assigned a critter and they had 15 minutes to figure out how to portray that critter so that their classmates could ID it.

This group created a Beaver Lodge and had beavers swim in with sticks from their winter feeding lodge, and one added mud to further insulate the lodge.

I won’t share them all, but this group represented a Red Fox, except that the tail (scarf) got caught. The Xs created by humans were intended to be the X in each print.

And then on Sunday, while hiking in to a wetland a mile plus behind our home, My Guy and I spotted Snowshoe Hare tracks aplenty, but something else caught my attention.

I thought it was a spider in the Hare print because I’ve seen so many on the snow in this area this winter.

That is until I took a closer look and realized it had five legs rather than eight. Oops, I wonder what happened to the sixth leg.

Despite the lack of that other leg, it moved across the snow as best it could. This being a Snow Fly. As for that missing leg, Snow Flies self-amputate so that ice doesn’t enter body. It’s a fighting chance to survive the frigid winter.

Oh, and it’s not always about tracking, especially when a bit of bird calls and color drew our eyes skyward, where we watched and listened to a flock of American Robins, and . . .

Cedar Waxwings on a chilly winter day.

On Monday, My Guy and I made a quick journey around the trails at Viles Arboretum in Augusta, and I actually never took a photo. Yikes. I bet you didn’t think that was possible.

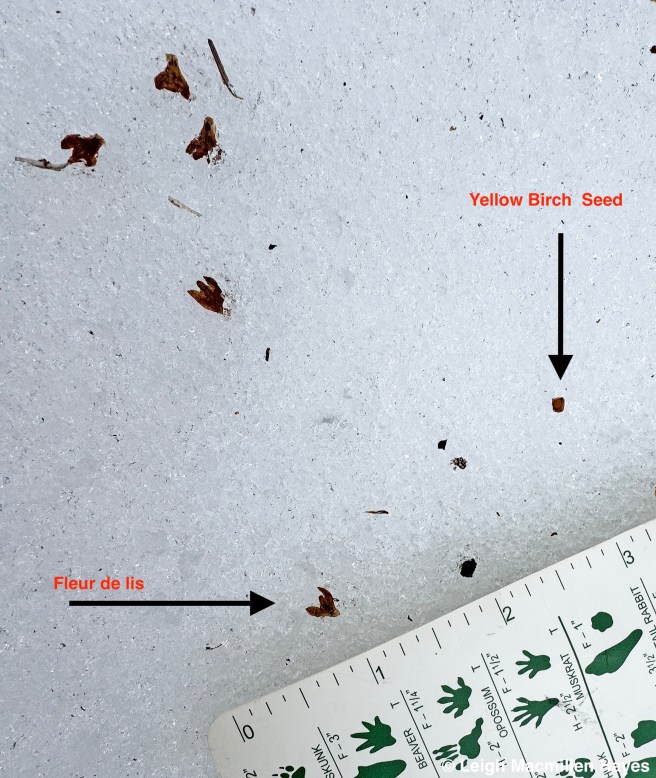

On Wednesday, fellow Master Naturalist Dawn and I spent time at Loon Echo Land Trust’s Tiger Hill Community Forest in Sebago with a group of people curious to learn about tracking and came away jazzed by their level of interest and involvement as they took measurements and noticed details.

On Thursday, My Guy and I climbed the Southwest Ridge Trail on Pleasant Mountain in Denmark, where there wasn’t much snow given the trail’s orientation to the sun, but we did spot quite a few deer prints and runs. I love how deer follow the same trail, making it easier to get from a sleeping area to a feeding area within their “yards.” For years. We’ve lived in our house for over 30 years and I can tell you where the deer runs are located. Always have been. I pray they always will be.

Despite the lack of snow, the views were grand. And he was pleased that nature didn’t slow me down too often.

On Friday, I spent a few hours with these four and two more as we explored at Loon Echo’s Crooked River Forest in Harrison.

One of our cool discoveries was a Porcupine path that led to a den, in the same location we found it last year. I was happy to know that there was no need to move.

And based on the hoar frost around the entry way, we surmised there was at least one Porcupine inside.

We left it or them alone and followed the well worn track in the opposite direction to the feeding tree, an Eastern Hemlock, where there were plenty of downed branches cut at the typical rodent’s 45˚ angle.

And we found the curved scat that had dropped from the animal as it fed while sitting on a branch up in the tree. Happiness is!

And then we made a discovery that didn’t make sense at first, but I think we interpreted correctly based on the evidence provided. At least this is our story: Deer tracks led to the steep river embankment, which in this spot was two-tiered before it reached the water. From our spot at the top of the embankment, we spotted deer tracks leading down to the next level and saw this crazy writing in the snow. And then it occurred to us. There were no human prints or any other prints in the area down there. Only the deer prints leading to it. And on the ice-covered river below, more deer prints. What we surmised is that the deer leaped down to the next level because we could see a couple of prints on the embankment leading to it. And then slid. This way and that. And as it tried to steady itself, it fell on its side, and did a full body slide all the way down the ice and over the leaves and directly down the second embankment to the river below, where it continued to slide once it got upright, and wobbled a bit (wouldn’t you?) before it crossed to the other side.

Regrettably, I didn’t take any more photos, but we discovered that at least one more deer had done the same to the left of where we stood, and it ended up sliding down in the same spot as this one pictured, all the way to the river.

Knowing that deer have traditional runs or paths, I can’t help but wonder if this is one of them, and usually the trip down to the water isn’t quite so perilous. You can bet I’ll check again.

And finally today dawned, and after some errands, I headed into the woods to reset our game camera. That’s when I began to spot blotches of black on the snow. Huh?

Not blood from an animal. What could it be?

Some were rather big. But a closer look soon gave me the answer as it looked like pepper grains were on the move.

After a frigid few days and before what could possibly be a real snowstorm tomorrow night and the next polar vortex to follow, Springtails (Snow Fleas that aren’t really fleas and don’t bite) were doing their thing–springing from the furcula, an appendage under their abdomens, as they fed (though I could only imagine the feeding part because I couldn’t see that action) on decaying plant matter.

What I really wanted to see, I suddenly spied–a predator in their midst! The spiders that I often find on the snow, feed on Springtails. Tada!

Dear Readers, this has been a long post, and even the Robin would agree. But I wanted to share all of these amazing things with you with hopes that you’ll head outside and look around and see what you might see. The stories are yours to interpret. It’s really so much fun. Thank you for sticking with me.

I received the best compliment this morning when a current Maine Master Naturalist student sent me some track photos to check on ID: “Thanks for your assistance- after your presentation I’m finding tracks in places I normally frequent yet I wasn’t paying attention!” ~J.K.

Thanks for paying attention. Happy Tracking!