So here’s the deal. A friend and I were supposed to lead a tree workshop today, but the weather didn’t cooperate. I’m not complaining about the few inches of snow–it’s the sleet that came first and the rain that is now eating up some of the snow that bothers me.

That said, I’m going to take you on a deep dive to meet some of the trees of Maine in their winter format. We are so fortunate to live in a section of the country where there is such variety, but that doesn’t mean we all know a species with just a quick glance. Oh, maybe you do. I know I sometimes have to slow my brain down before my mouth makes an announcement.

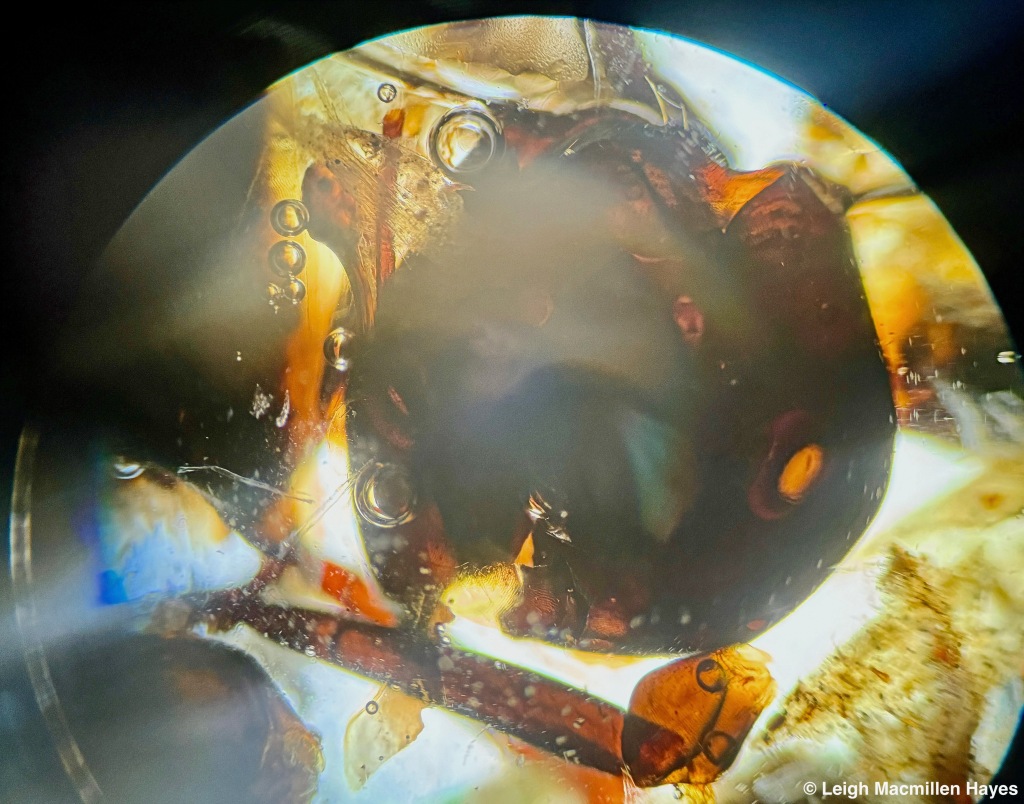

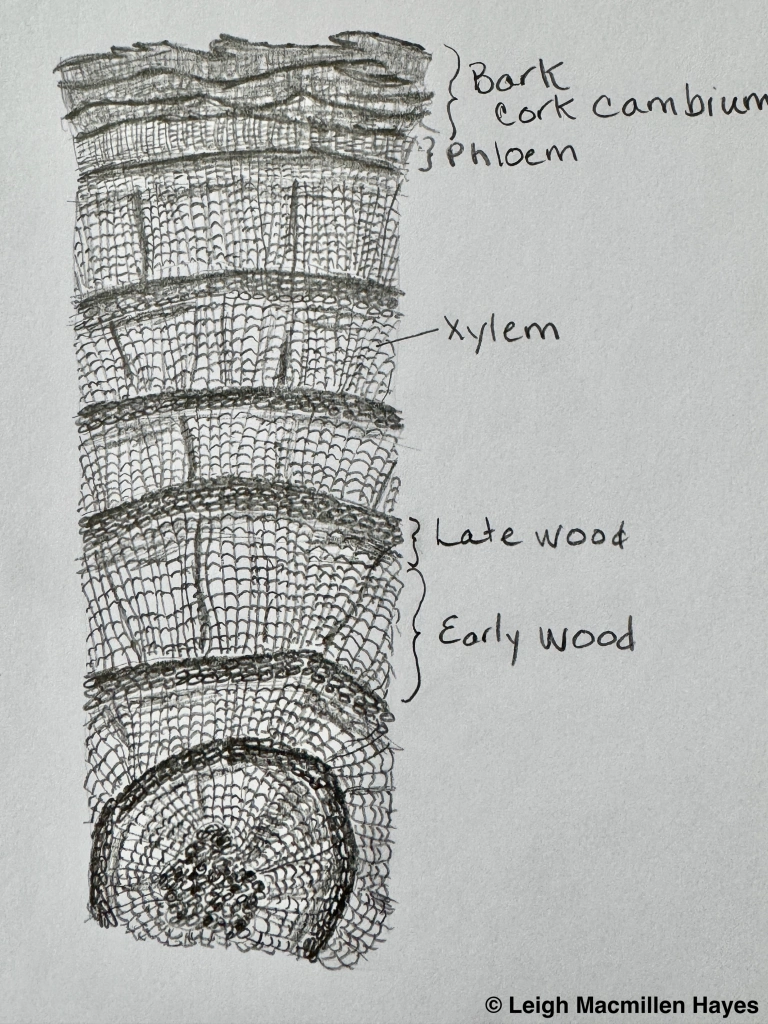

I found a drawing of a tree “cookie” on the internet this past week and decided to recreate it in one of my sketch books this morning. I like it because it helps me better understand how a tree works.

The key factor here is that trees are made of . . . wood. You knew that. But, what exactly is wood? Think scaffolding and plumbing. A tree needs structure to grow so tall, but it also very much needs food and water. Two components, therefore, make up the wood: Xylem and Phloem. Xy (think sky high) transports water from the roots, while Phloem (Think flow low) moves the sugar made in the leaves via photosynthesis during the summer down through the trunk.

As you can see from the sketch, the Phloem is only present on the outer layer of a tree–right under the bark. The Xylem makes up the majority of the wood.

And all those Xylem cells–they are made up of an outer wall of lignin, which gives the trees structure, and an inner layer of cellulose, which provides flexibility. Some trees, like Gray Birch, have a high concentration of cellulose, thus allowing them to bend under the weight of the snow, usually, but not always, without snapping.

The Xylem actually acts as a bunch of straws pulling up water, along with nutrients and minerals, from the soil. But can we actually see this action occuring in the trees? The answer is a resounding, “No.” It’s not at all like we might use a straw to slurp up a frappe, but rather a passive flow, where the water molecules evaporate through the stomata (holes in a leaf surface, similar to our pores), they draw other water molecules upward from the soil to the roots, and the roots to the Xylem, and the Xylem to the leaf, and the leaf to the air (Think water vapor = Transpiration).

Going back to the sketch above, the early wood of each year, which occurs in spring and summer, is much lighter in color than that of the late wood, but the two together create a ring documenting that particular year.

The heartwood, which isn’t labeled, is the inner core. It provides support for the trunk and is actually dead because over time the Xylem gets clogged up with resin. And each year more of the tree dies from the inside out.

If you are still with me, let’s get to the actual trees I want you to meet.

Up first is a White Ash, Fraximus americana. This is one of those species that once you get to know it, you spot it from a distance because of the pattern of the bark. What exactly is the pattern? Well, I see intersecting ridges that form obvious diamond-shaped furrows which appear as an X or cantaloupe rind, but others see an A for Ash, and still others see a V, and some even spy a woven basket. The thing is, whatever pops out for you and will help you identify it in the future should be your go-to image stored in your brain.

One of my favorite things about Ash bark is that it is corky and after a storm, you can pinch water out of it or stick a fingernail into it.

The twig is quite stout and ashy-gray in color. The buds are opposite, and the terminal bud at the tip of the twig is rounded or dome-shaped.

One of the features that speaks to the color of this Ash is the shape of the leaf scar below the new bud. A leaf scar is where last year’s leaf was attached until the end of the growing season. At that time an abscissa layer formed between the petiole (stem) and the twig. The leaf fell off and the tree healed the wound quickly with a protective cork. The bundle scars are part of the pipeline as they were the vascular tissue contained in the petiole of the leaf. Each tree has its own number of bundle scars located within each leaf scar.

Back to the shape–can you see how the bud dips a bit down into the leaf scar rather than sitting across the top of it. This tells us it is a White Ash and not a Green Ash. Add to that the fact that the terminal bud is not hairy.

And my rendition of White Ash bark.

Up next is another favorite. Oh never mind. They all are my favorites. This is a Red Maple, Acer rubrum.

The bark is light to dark gray in coloration and almost smooth with crackled, vertical, plate-like strips. It curls outward on either side, and on older trees, look for tails to curl out on ends of strips.

Sometimes, it is difficult to determine if a maple is Red or Sugar, but one of the clues I look for is the Bull’s Eye target on the bark. There are several on this one, can you see the rounded patterns that aren’t completely formed? The target is formed as a reaction to a fungus.

Again, this is a tree with opposite branching. So one of the keys to tree ID is to know if the branching is opposite or alternate. I love this mnemonic devise: Very MAD Horse. Trees/shrubs with opposite branching include Viburnums like Hobblebush; Maples; Ash; Dogwoods (unless it’s the Alternate-leafed Dogwood); and Horse Chestnut.

As you can see, the buds are red. This is another clue that it’s a Red Maple: there’s always something red on the tree. Sugar Maple buds are much smaller and brown.

Each bud has 3 or more scales and each scale is fringed with little hairs. The twigs are straight and also red, especially newer wood.

My rendition, though I do need to work on the target.

And the twigs/buds, which are already becoming more bulbous. I have to be honest with you. As a kid and young adult, I did not know that buds for the next year form in the previous summer and overwinter under those toasty scales for protection. I suppose I never actually thought about it. But of course they do, because that’s when the tree has the most energy. In April, they will flower, and by May the leaves will begin to form.

But right now, it is snowing again–YAHOO!

American Beech, Fagus grandifolia, is our next exhibit. These trees can tolerate shade and I will never forget when a local forester showed some students a tree cookie that was about two inches in diameter and he asked one to count the number of tree rings. Sixty years old. Yes, they tolerate shade.

In fact, Beech trees tolerate a lot. Typically, the bark is smooth, unless . . . there are cankers or blisters dotting it that are caused by the tree’s reaction to a fungus that gains access via a tiny puncture made by Beech Scale Insects. The insects are teeny little things, with fluffy white coatings, and they congregate on the bark for 50 weeks, where they pierce the tree repeatedly to get sap. For two weeks of their lives, they can fly. The rest of the time, they stay put and sip.

Another thing that Beech trees tolerate is Bear Claw marks and if you are a follower of wondermyway, I need say no more. If not, search for bear claw trees in the search bar.

They also tolerate humans carving initials. More than they should; And those initials and those bear claw marks will always be present as long as the tree lives. In fact, they’ll be in the exact same place at the same height that they were originally made, but they’ll have widened a bit each year.

All trees grow out from the heartwood, and up from the uppermost branches. So if you place a trail blaze on a tree, it will always be in the same spot, you just need to make sure that you don’t screw it all the way into the tree or the tree will grow around it eventually. (Rule of thumb: leave about two inches between the sign and the tree; and check it each year)

Beech twigs are deep brown with white lenticels. Oh yikes. We haven’t talked about lenticels yet. All trees have them. A lenticel is like the pores in our skin and allows the tree to exchange gases. Lenticels come in a variety of shapes including raised circular, oval, and elongated. (Remember, leaves have stomata for the same purpose.)

As you can see, the bud is sharp-pointed, covered with many scales, and a delightful golden brown. Some see it as a cigar. That description doesn’t work for me, but it is tapered at both ends. And really, nothing else looks like this in the north woods. While this photo is of a terminal bud, the twigs and buds are alternate.

Leaves on Beech are marcescent and wither on the trees over the winter. In fact, if there is a sudden breeze and the leaves start to rattle, I’ve been known to become rattled, thinking there is something or someone else in the woods with me.

And this time I present American Beech, which can be blotched with crustose lichens (look like they’ve been painted onto the bark).

And a twig, showing the growth rings, which occur where the previous year’s terminal bud had been.

And now for an upclose look at the bark of Northern Red Oak, Quercus rubra. (I almost wrote Maple, and for some you’ll know that as “my mouth or in this case my fingers before my brain”–like when I call a Beech, that I know darn well is a Beech, a Birch. Such is life.)

Red Oak bark is greenish brown or gray and has rusty red inner bark. When I look at it, I see wide, flat-topped ridges that run vertically parallel but also intersect like ski tracks. Shallow furrows separate the ridges.

The red inner bark is especially noticeable in winter.

The twigs and buds are alternate in orientation. The twigs are smooth, and greenish brown, but the buds are much more intersting as they occur in a crown at the tip of the twig. Each bud has many scales and matted wooly hairs. I love their chestnut brown color.

My rendition of a Northern Red Oak.

And the twig. As you can see, there are also buds along the twig, not just at the tip, and they do grow alternately. Also, Oaks have marcescent leaves as well, though most fall off before spring. I did spot a very mature Red Oak the other day that is overwhelming full of dried leaves.

And now let’s meet several members of the Birch Family. Up first is the Paper Birch, Betula papyrifera. You may know this commonly as a White Birch, but I prefer Paper, and will explain why after introducing you to its kin.

Betulin is a compound in the cells of the outer bark that is arranged in such a way as to reflect light and make it appear white. The betulin crystals provide protection from the sun as well as freeze/thaw cycles. It also protects the tree from pests. And to top it off, betulin is the reason the bark is a good fire starter as its highly flammable and waterproof. Your go-to for a rainy day fire. It was also used to build birch bark canoes.

Young Paper Birch bark is white, but often with an orange and pinkish tinge. It has thin, horizontal, light-colored lenticels. As it matures, the bark changes from white to creamy white. Sometimes I even see the colors of a sunset in it, including some blue in the winter.

The outer layers separate from the trunk into curled sheets, thus the paper nomenclature. But, I caution you not to pull it off, as prematurely exposing the cambium layer may harm the tree.

Older bark can sometimes make this tree more difficult to identify because it has gray sections of rough, irregular designs, especially around the base.

One of the features I look for on a Birch to determine if it is a paper, besides the curly bark, is the mustache that is drawn over the branches on the trunk. In the photo above, the branches are no longer there, but do you see two mustaches? Sometimes both ends droop down even more.

The twigs of Paper Birch are alternate, as are the buds. New growth on a reddish brown twig is usually hairy. And buds may grow on shoot spurs, which I’ll show you in a minute.

Paper Birch buds are covered with scales that are sticky, especially if squeezed. And for the most part, they are not hairy.

Their flowers are in the form of catkins, with tiny seeds protected by fleur de lis-shaped scales. Paper Birch catkins appear mostly in clusters of three.

My rendition, though I need to sketch one with the branches and mustaches. Another day.

This sweet tree has long served as a reminder to me to go off trail and look for a mesmerizing spring of water. Oh, not every Yellow Birch reminds me to do that, but I know where I took this particular photo and the spring is about an eighth of a mile behind it.

Yellow Birch, Betula alleghaniensis, has bronze to yellowish-gray bark that is shiny. And it too curls, but this time it curls away in thin, ribbony strips, giving the bark a shaggy appearance.

One special note about Yellow Birch, and the same is true for one of our conifers that I’ll discuss soon, is that the seeds struggle to germinate on the forest floor, but give them a moss-covered rock, or tree stump, or nurse log, and bingo, a tree grows on it. As it continues to grow, the roots seek the ground below and if it is upon a stump or log that eventually rots away, you have a tree in the forest that appears to stand on stilted legs.

So I mentioned for Paper Birch that they have spurs of stacked buds and so do the Yellow Birch. The bud appears at the end of the stack and by the leaf scars left behind you can count the age of the spur.

The twigs are not hairy, but they have their own unique distinction. I wish I could share this with you, but you’ll have to go out on your own and find a Yellow Birch twig–the distinction is a scratch ‘n sniff test. If you scratch it and smell wintergreen, then you have found a Yellow Birch.

Three to four catkins appear on Yellow Birches, but they are not clustered, so that’s another clue as to the color/name of the tree.

My Yellow Birch.

Gray Birch, Betula populifolia, is an early succession tree, meaning when an area has been cleared, this is one of the first trees to grow. Unlike Paper Birch, which can live to the ripe age of 90 or so if conditions are right, and Yellow Birch that can survive over 200 years, Gray Birches are not long lived and many only survive 30 – 60 years.

Often these trees are leaning, even if they don’t have snow piled upon them. And their lower branches remain on the tree, where Paper Birch tend to self-shed. The branches are pendulum, leaning toward the ground in an arc. And below each branch or where a branch had been, is a triangular shaped gray beard.

I mentioned earlier that I prefer Paper over White for a Paper Birch, and one reason is because Gray Birch also appear white. But Gray does tend to have a dirtier look to it and it has little to no peeling.

Gray Birch twigs are very fine, and super warty. In fact, it’s fun to run your fingers over them and feel the lenticels, like someone glued salt crystals to them. Their coloration is dull gray to brown and they are not hairy, nor do they smell like wintergreen when scraped.

The red brown to greenish brown buds are short, with scales that also lack hairs, and they are not sticky.

As for catkins, most appear in early spring as a single one or a pair. If you spot a single one in the fall/winter, then it is usually a solitary male.

Tada. A Gray Birch.

The final deciduous tree is a Quaking Aspen, Populus tremuloides. (I bet you are thinking, “Oh phew, she’s almost done, but never fear, I have four conifers to share with you.)

Quaking Aspens are also early succession trees, and they can grow from seeds, but also like to root sprout. One tree in Utah has over 50,000 stems from one root and covers over 100 acres.

The bark is grayish-green, and more so green on a wet day like today. It also has horizontal bands that become more evident as the tree matures.

The buds of the Aspen are alternate, shiny and dark brown. They aren’t sticky like its cousin, the Big Tooth Aspen. I think the most defining feature of these buds is their varnished appearance. My experience is that Porcupines love them.

The twigs are thick, smooth, and chestnut brown.

I haven’t sketched this tree yet, so I’ve added it to my to-do list.

Balsam Fir, Albies balsamea, smells like a Christmas Tree. This is a conifer that stands straight and tall as if in military fashion.

Its bark is pale gray and smooth, but covered with small dash-like raised lenticels and blister bumps filled with a sticky resin. Pick up a stick when there are puddles nearby, poke a blister and let the resin ooze onto the tip of the stick and then place the stick into a puddle and watch the essential oils form and change shape on the water’s surface. This works best on calm water.

Being an evergreen, Balsam Fir have leaves (needles) that are always on them, though they lose some each year. And gain new ones, of course. If you were to remove all the needles, you’d find a smooth twig.

The needles appear to be arranged in a flat manner, but actually spiral around the twig. They are shiny above and have two rows of white lines below, which are actually the stomata.

At about an inch in length, they attach directly to the twig and some have notched tips.

Their cones are 2 – 4 inches in length, and are dark purple before maturity. The unique thing about Balsam Fir cones is that they stick up from the twig rather than hanging down like other conifers.

I think I found the only Balsam Fir in the forest that wasn’t military straight, but as I always say, “Not everything reads the books we write.”

And my offering of the twig.

Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis, has cinnamon red to gray bark. As the tree matures, the bark features narrow, rounded ridges covered with scales that look like they could flake off, but they are rather sturdy.

Overall, the tree has a lacy look and its leader bends over making it appear to dance in the forest.

Hemlocks are like Yellow Birches, in that they need a moist area to set root and often grow on moss-covered rocks or tree stumps or nurse logs, so called because they are rotting trees that provide nurturing places for other things to take form.

While the Balsam Fir needles are about an inch long, Hemlock needles are about a half inch in length. And whereas the Fir needles are directly attached to the twig, Hemlock needles are attached via tiny petioles or stems. And the underside also has two rows of stomata, but so close together, they may appear as one.

The twigs are very fine and very flexible.

Hemlock cones are about 3/4 inch in length ( I got carried away with the size of this one, or you could say its a macro look at the cone) and oblong in shape. They are pendant, meaning they hang off a slender stalk. And small rodents and birds love to eat their seeds that are attached as a pair to the underside of the scale.

Oh, did I say they are all my favorites? Well, maybe my favoritist of all is the Red Pine, Pinus resinosa.

The bark is reddish brown to pinkish gray. I see it as a jigsaw puzzle, but my friend and fellow naturalist Dawn, sees it as a topo map.

Its broken into irregular, thin, flaky scales, that you may see on the ground surrounding the trunk.

As the tree matures, those scales are broken by deep fissures into irregular looking blocks.

Red Pine was of particular importance during the 1930s to 1960s, when the Civil Conservation Corps (CCC) planted plantations of this species on former pastureland as a reforestation project. Once in a while I stumble upon a grove of Red Pines planted in rows and realize that I’m in such a plantation. They were considered a cash crop for telephone poles.

The orange-brown twigs of the Red Pine tend to curve upwards and if you look upward you’ll notice that the needles are all clustered at the end, giving them the look of bushy chimney sweep brooms.

The needles are in bundles of two, and they are about 4 – 5 inches long. If folded in half, they break cleanly.

Red Pine cones are egg-shaped, about two inches in length, and lack prickles like some other species sport. It takes two years for them to mature.

What do you see? Jigsaw puzzle? Topo map? Or something else entirely?

Finally, we have reached the last species for today, White Pine, Pinus strobus. I’m showing you the bark of a mature tree, but if you look at a young pine you’ll note it is very different with its smooth, pea green bark.

Mature trees, such as this, have dark gray to brown bark, with long flat ridges, and deep, dark furrows. What I love about mature White Pines is that the flat ridges have lines that resemble writing paper and I love to write.

White Pine twigs are slender and gray-green to orange-brown. Bundles of five needles is the count for White Pine, which is cool because it spells its name: W-H-I-T-E, or M-A-I-N-E, since it is our State Tree. (Please remember that Red Pine has only two needles in a bundle, and doesn’t spell its name.)

Cones are 4 – 8 inches long, cylindrical, and also take two years to mature. And it takes a Red Squirrel about 2 minutes to peel back the scales and eat all the seeds as if they were corn kernels on a cob.

Dear readers, if you made it this far, I thank you for sticking with me. I do love to write and maybe I’ve written too much.

But I hope you’ll venture out and get to know these trees better by studying their idiosyncrasies and coming up with your own mnemonics to remember their names.

May you become tree wise and may I continue to learn about and with the trees.

You must be logged in to post a comment.