I love that I can step out the back door and explore hundreds of acres of woods or follow a path, cross a road, and step into a town park protected with a conservation easement. Lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time in the park, for starters because I love to spot the Mallards and look for Winter Stoneflies, but also because I’m working on getting to know bryophytes and lichens better. Of course, I could to that anywhere because mosses and lichens grow everywhere. And do not harm the substrates upon which they grow. In fact, they may actually help as in the form of mosses retaining water.

So, I invite you to step across the Bob Dunning Memorial Bridge and into Bridgton’s Pondicherry Park. Sixty-six acres of forest beside Stevens and Willet Brooks, with stonewalls, an old spring, and carved trails, including one that is ADA accessible, though in the current conditions, it’s icy and micro-spikes are the best bet for staying upright.

I’m almost certain these two ducks are named Donald and Daffy, but what I do know is that they laugh. A lot. Or at least that’s what it sounds like when they quack.

Finally, the reason I invited you along for this journey. One of my favorite little mosses. Meet Ulota crispa, or Crispy Tuft Moss (and Curled Bristle Moss and Crisped Pincushion . . . and probably several other common names). This moss is an acrocarp in form, meaning that the main stem generally grows upright and the capsules and seta or stalks that hold the capsules grow from the tip of the main stem. Usually, they grow upright that is, but in the case of Ulota crispa, they orient horizontal to the ground.

On this tree trunk, you might notice the pale green crustose lichen (crustose meaning crust-like and tightly pressed to the surface of its substrate) and the brown spiderwebby structure of a Frullania liverwort. Like mosses, liverworts are also considered bryophytes–meaning they don’t have a vascular system like plants and trees; nor do they produce flowers or seeds.

Ulota crispa grows in little tufts between the size of a nickel and a quarter. On some trees you might find one or two and others, such as this one, there are many.

My walk in the park was actually a self-assigned quiz because a friend and I had visited a few days prior and I wanted to make sure I could identify species on my own. As I always say when I’m tracking by myself, I was 100% correct in my ID.

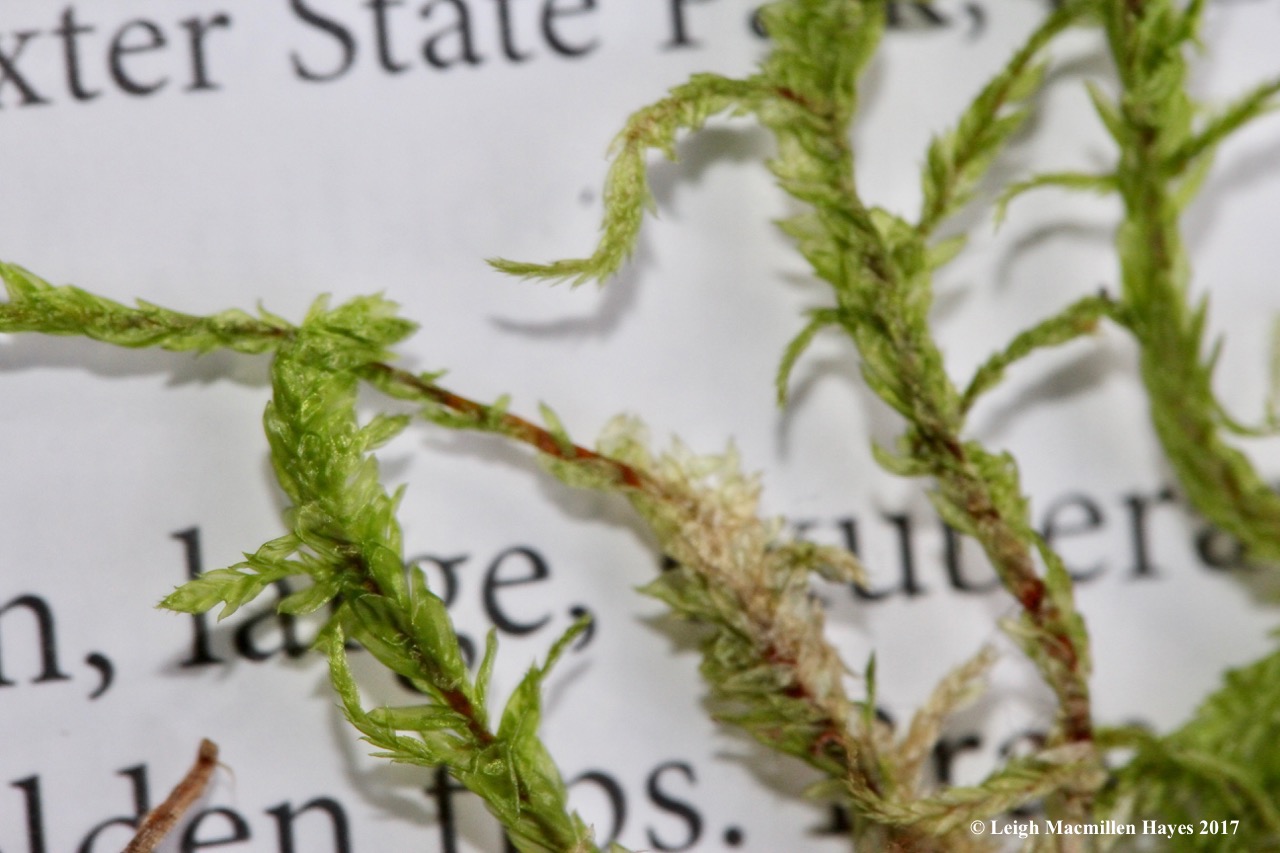

But actually, this quiz did give me time to slow down and notice features, such as the thickness of the Brocade Moss, aka Hypnum imponens. This one is a pluerocarp in form, because the moss grows mostly prostrate, has many branches, and the capsules and seta (stem supporting capsule) arise from a side branch rather than the tip like that of the acrocarp.

I found one downed tree (and I’m sure there are many others under the snow) that looked as if it was covered with a carpet, a Brocade carpet. Given that a brocade fabric has a raised design, this common name seems to fit, though my research informs me that the Latin Imponens is the root for “imposter.” Apparently it can have different looks. That’s something I’ll need to pay attention to in the future.

Delicate Fern Moss, or Thuidium delicatulum, is another pluerocarp species. The fronds really do look like miniature fern fronds, in fact, twice-cut in fern lingo. But that’s a topic for another day.

I found the Delicate Fern Moss growing on a tree trunk, but also on a rock. Mosses don’t have actual roots, because remember, they are non-vascular plants. Instead, they have rhizoids, which look rather root-like, that anchor the plant to the substrate.

So how do they get water and nutrients? Via their leaves. And they have the unique ability of being able to dry out completely and stop growing, but pour water on them, or visit them on a rainy day after a dry spell, and they’ll begin growing again and turn from brown to green as photosynthesis kicks back into action.

If you been in the park, then you may now this stream below the Kneeland Spring. And you realize that I’d probably already spent an hour on the path and hadn’t moved very far. The old joke that I can still see my truck in the parking lot doesn’t work this time though because I had walked there. But I could still see the parking lot.

What attracted me to the stream was the sense of color. On a bleak winter day, the view was breathtaking in a subtle way.

In particular, the bright green of a plant that isn’t a moss or liverwort, but rather a vascular plant known as Watercress. It grows in natural spring water, thus its abundance below the spring from which this water flows.

While I was admiring the Watercress, I met a moss that I swear I’ve never laid eyes on before, but don’t think I’ll ever forget going forward: Willow Moss, aka Fontinalis antipyrectica. Its one that prefers to be submerged, thus its location. When the water is warmer, I need to get to know it better, but it almost looked like the leaves were braided.

The funny thing about this spot is that as I was looking down, a young couple walked along the trail above me. In an instant, the young man and I made eye contact and at once recognized each other as we are neighbors. He said, “I wondered who was down by the stream.” He wasn’t at all surprised.

Because the snow is beginning to melt, I finally saw an example of the poster child for acrocarpous mosses: Common Haircap Moss or Polytrichum commune. Here are a couple of easy ways to ID it from other haircap species: when dry, the leaves don’t twist as they fold upward toward the stem and the leaves have reddish tips.

Mixed in with the mosses were some little structures that actually remind me of caterpillars. They are also non-vascular and are associates of mosses, these being liverworts. Bazzania trilobata does not have a common name as far as I know. That’s probably a good thing because it forces me to learn the scientific name.

A small piece may have followed me home and stuck itself under the microscope. Liverworts are also small and where a moss has leaves arranged in more than three rows, a liverwort has two rows, like this one. That said, some have a third row underneath. Another key is that while mosses often feature a midrib, liverworts as you can see by this example do not. There’s more, but that’s enough to get started.

Mosses and liverworts aside, I had been looking for examples of this foliose lichen upon a previous visit, and finally found this one. It’s one of the ribbon lichens, but I haven’t yet figured it out to species. And I don’t know if it grows on anything other than Eastern White Pines, for that is where I see it.

Lichens come in four forms. Earlier I mentioned crustose: crust-like or pressed against the substrate; foliose–foliage-like or leafy; fruticose: upright and pendant, think grape branch; and squamulose: with little raised scales.

So, which form is this? Ah, the quiz is now in your hands. Crustose, Foliose, Fruticose, or Squamulose. I’ll tell you it isn’t the latter. Of the first three, which is it?

The little black discs or bumps are its reproductive structures.

Here’s a great take-away from Joe Walewski’s Lichens of the North Woods: “Successional stages of lichen communities on rock progress from crustose lichens, to foliose lichens, and then on to fruticose lichens. In contrast, successional stages for lichen communities on tree bark follow an opposite pattern. Many crustose lichens are a sign of an older successional lichen community.”

If you answered my question above as the form being crustose, you would be correct. Common Button Lichen or Buellia stillingiana.

This next one pictured above is among my favorites. Maybe it’s because though I find it on other trees, I love how it appears between the “writing paper lines” on the ridges of Eastern White Pine bark. Known as Common Script Lichen, or Graphis scripta, you might see it year round as white spots on trees but the squiggly apothecia (reproductive or spore-producing structure) appear only when it gets cold enough.

And here again: same crustose form, different crustose colors. Do you see at least three colors? Two shades of green surrounded by a blueish-grayish white? The white fringe is called the prothallus, a differently colored border to a crustose lichen where the fungal partner is actively growing but there are no algal cells. Though named the Mapledust Lichen, Lecanora thysanophora, it grows on several species of trees just to keep us all questioning ourselves.

The final lichen of this journey, and believe me, there could be a million more, or maybe not quite that many, but . . . anyway, is the Common Green Shield. I’m realizing just now that I don’t have a fruticose lichen to share, but that I’ll leave for another day. This Flavoparmelia caperata demonstrates the foliouse form. One that my lichenologist friends, Jeff and Alan, describe as one you can easily ID while driving 60 mph. Of course, you should be looking a the road and not at the lichens or your cell phone, but should you glimpse it out of the corner of your eye, you can easily remind yourself that it is a Common Green Shield.

While finally making my way homeward, I was stopped by a sight that always invites a look. You may be tired of seeing it, but I hope I never am. The debris left behind by a Pileated Woodpecker.

There are at least two packets worth examining in this mess, and if you know what I mean, see if you can find them.

The tree was one rather gnarly Eastern White Pine and it grew near one of the old boundaries for the park was originally three different properties that were combined to create such an open space. You can read about that in Pondering the Past at Pondicherry Park. I suspect its growth pattern had something to do with being a boundary tree in an otherwise open area.

Do you see the bird’s excavation site?

And did you find this scat in the debris? Staghorn Sumac had been part of this bird’s diet prior to visiting the tree.

But carpenter ants were on the menu as well. Vegetable, Protein, Fiber. The perfect meal.

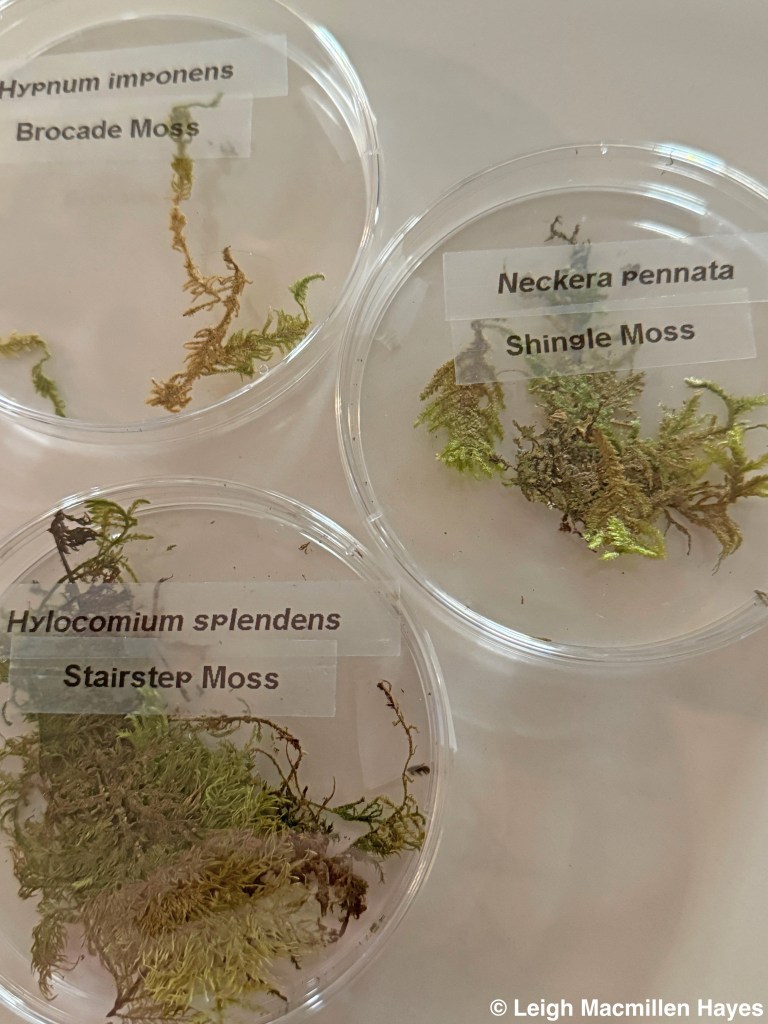

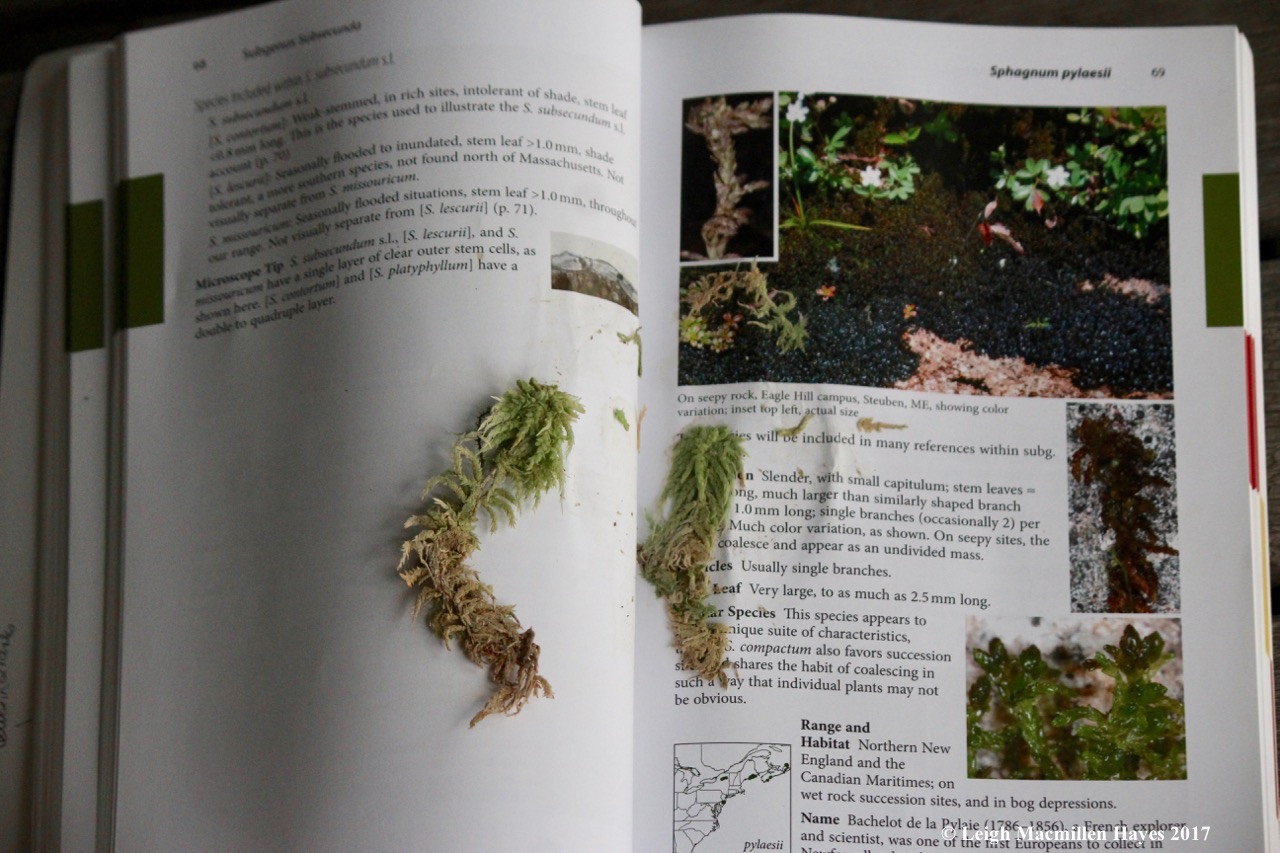

When I arrived home, it was time to do some organizing of my moss collection, some of these which I’d collected in the past and kept in Ralph Pope’s Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts: A Field Guide to Common Bryophytes of the Northeast.

The book is warped because, of course, most of these were damp when I placed them in it.

Here’s the thing about collecting mosses: only take just enough to study. Mosses can take a long time to grow, so you only need a small piece for closer inspection. As for lichens, if you need to, collect from those that have fallen off trees. Otherwise, let them be. They take even longer than mosses to grow.

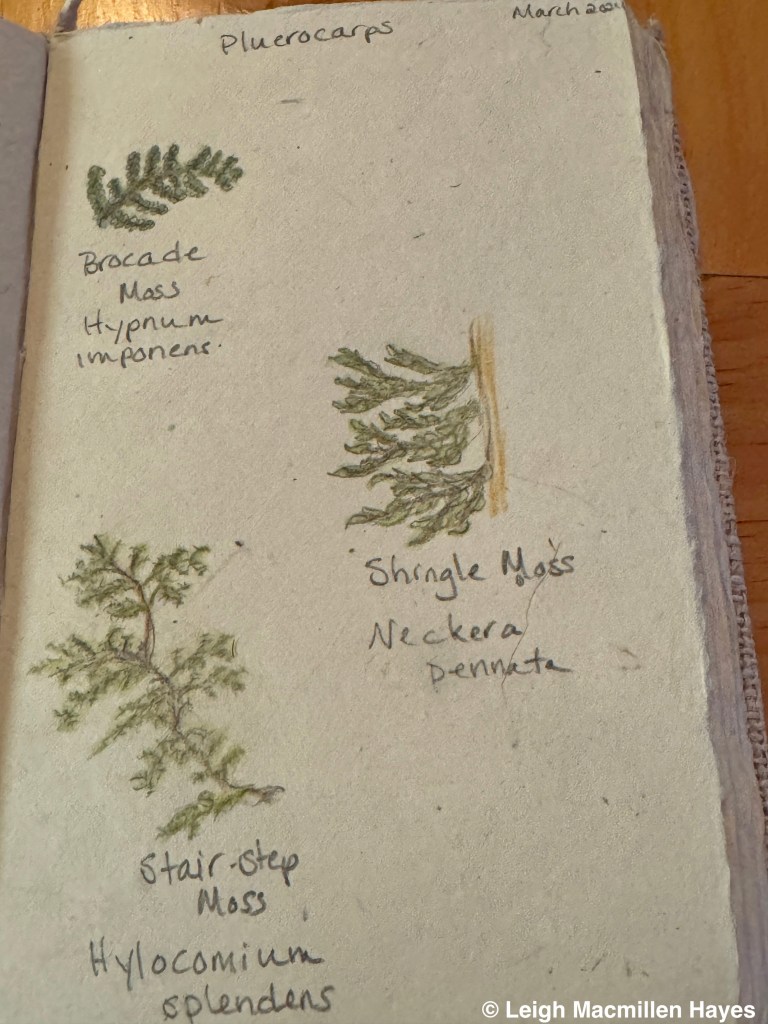

And I encourage you to spend some time trying to get to know what you meet up close and personal. Looking through a loupe and sketching help me.

Slowing my brain down and noticing. I love that I am finally making time to do this again. And taking topics that had often stymied me and trying, trying, trying to get to know them better.

While I was pondering once again in Pondicherry, I did notice that someone was pondering about me. I went with the expectation of possibly seeing an owl while spending time quizzing myself on all of these species, and indeed I did. See an ice owl that is.

You must be logged in to post a comment.