It’s been two years since we’ve spent time together, and to be honest, I kind of doubt this is my friend from 2021, but perhaps an offspring. Anyway, what I do know is that last year was not a mast year in my woods and so there wasn’t much food available–the type my friend prefers to survive the winter months. But this year–pine cones and acorns abound.

As I headed down the cowpath that marks one of the boundaries of our property here in western Maine, I knew instantly by the chortling that greeted my ears that things had changed for the better.

You see, my friend is a Red Squirrel. And he spotted me before I spotted him. And then he let me know in no uncertain terms that I was not welcome. What kind of friend is that?

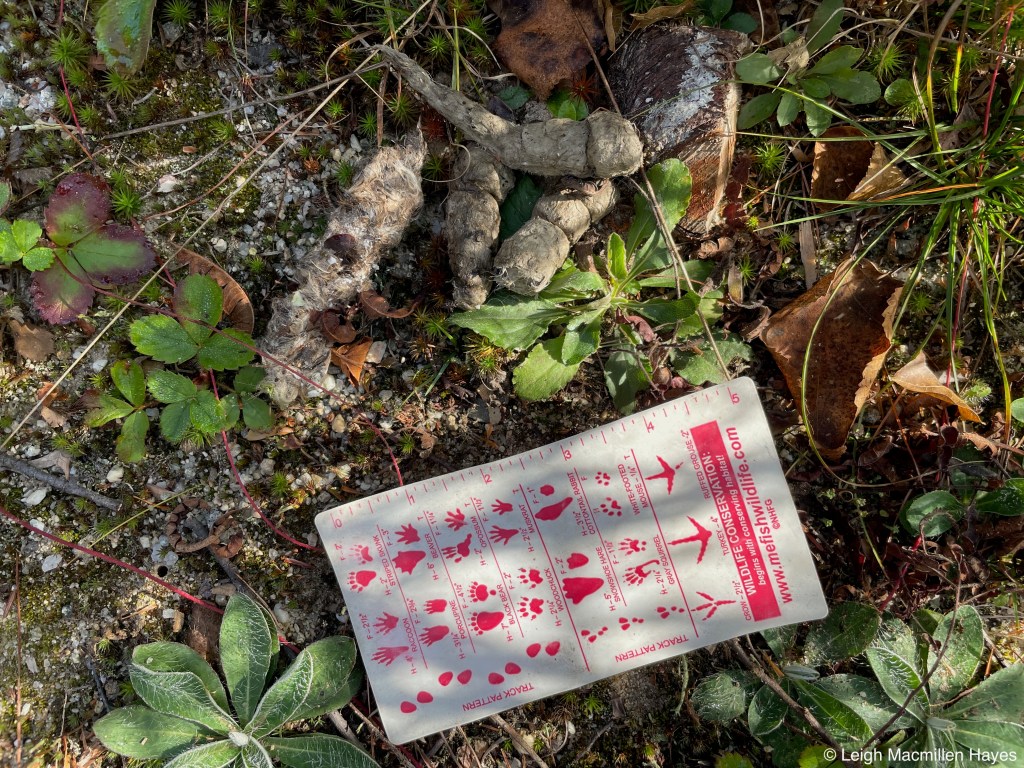

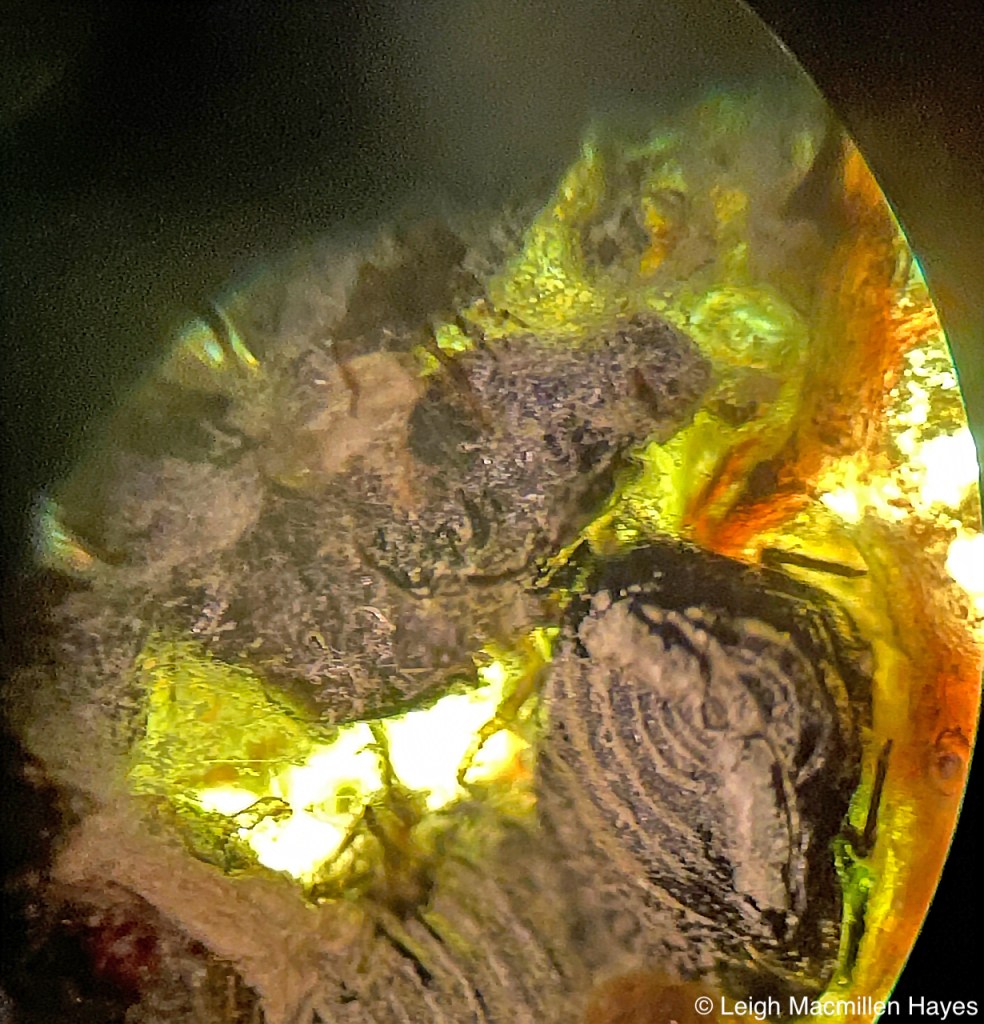

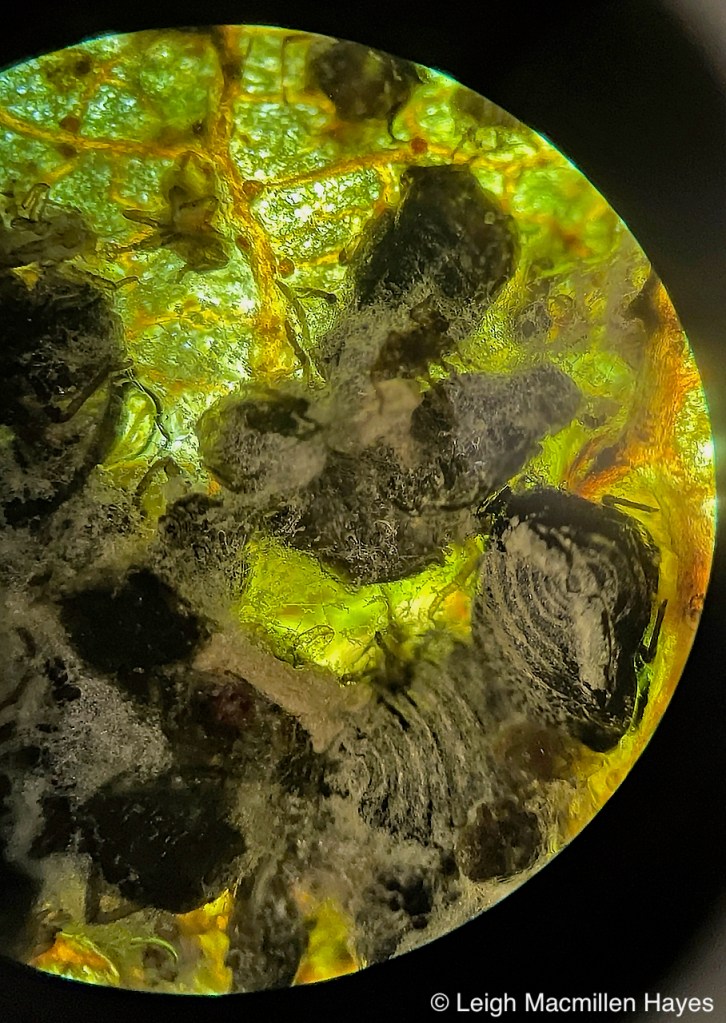

As I looked at the rocks along the inside path of the cowpath, I began to notice garbage piles Red had created, or middens as we prefer to call them, full of cone scales and the inner core or cob.

They were located in high places where Red could sit and eat in peace . . . that is until someone like me comes along, or worse . . . a neighboring squirrel, or even worse, . . . a predator. Given that a cone on this rock was only partially eaten indicated he’d been interrupted mid meal.

Maybe that’s why he continued to chastise me as he climbed higher up the tree.

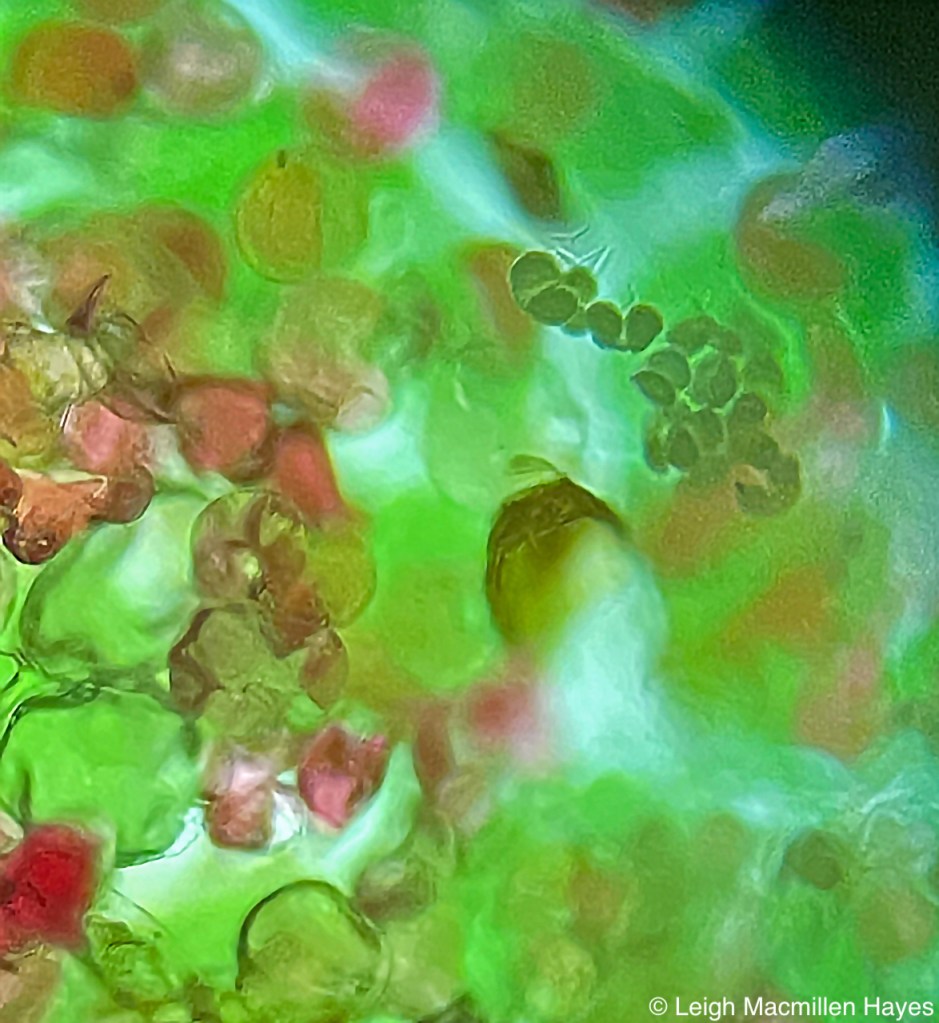

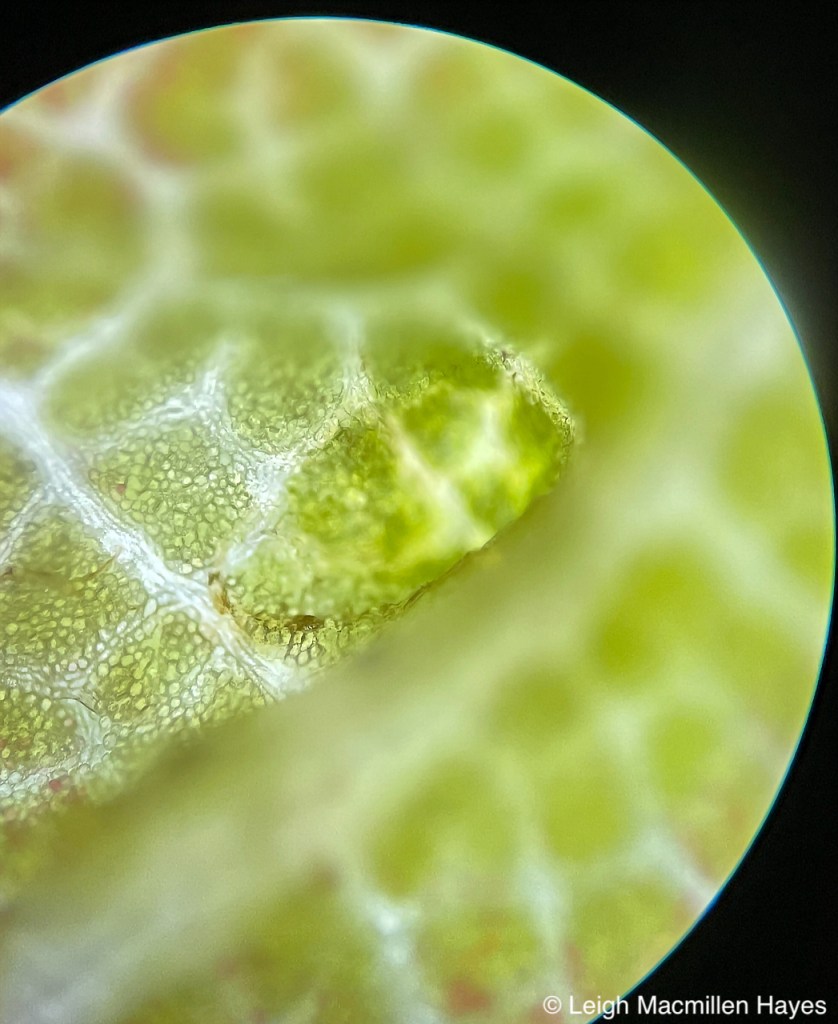

It takes at least two years for an Eastern White Pine cone to mature. And once they do, Red has a habit of squirreling his way out to the tips of twigs, gnawing the cone stem and letting it fall to the ground. If you spot a pine cone with closed scales such as this, count the number of scales and then multiply that number by 2. That’s the number of pine nuts the cone offers.

And trust that all are still tucked inside.

Pine cones are in a way like Common Polypody ferns and Rhododendrons in that they predict the weather. If it’s dry, the scales on cones will open. If rain and humidity are in the air, the former being today’s weather, the scales will close tightly, overlapping and sealing the seeds from the outside world.

While wet weather dampens seed dispersal, dry windy days are best and that allows the seeds to be carried away from the mother tree.

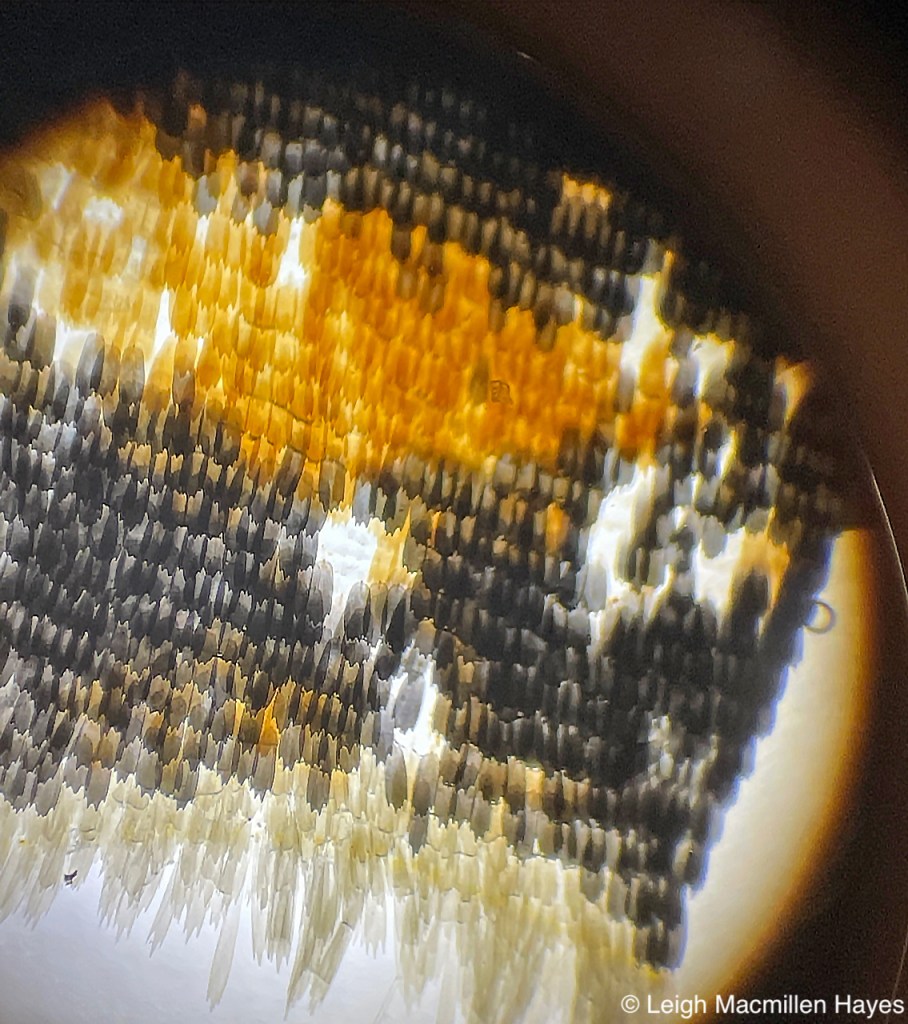

In the photo above, you can see where the two seeds had been tucked in, close to the the cob, while the lighter shade of brown indicates where the wings or samaras that help carry the seeds were attached to the outer scale.

And I can attest that the sap on the scales is still sticky even though this cone no longer had any seeds stored inside. The sap coats the cones because its the tree’s reaction of placing a bandaid on a wound when its been injured or in this case had a fruit gnawed free.

One would think that Red’s face and whiskers would be covered in sap, and that does happen, but just as it stuck to my fingers initially, eventually it wore off. And Red is much better at grooming than I’ll ever be.

To get to the seeds, Red begins by holding the cone with both front paws, and turns it in a spiral, tearing off one scale at a time. Quickly! And gnawing each tiny seed packet open. The seeds may be small, but they are highly nutritious.

He continued to watch, vocalizing constantly, as I explored his territory below.

Upon every high spot, including tree stumps, there was at least a midden, but also a few cones for possible future consumption, though I did have to wonder if some went uneaten because he realized they were open and thus not viable.

More of the same I found upon some of the cut pine stacks we created long ago that serve as shelter and . . .

Storage! I’ve been looking for a cache for the past few weeks, a squirrel’s food pantry, and today I located a few small ones that I know will grow in the coming weeks. Cool. moist locations like among the logs, but also in the stone wall, offer the best places to keep the cones from drying out.

As he backed up but still chattered at me, one thing I noticed about Red, which will help me to locate him in the future, is that he not only has a reddish gray coat, but between his back and white belly there is a black stripe. Maybe he’s disguising himself so he can go trick-or-treating this week and his neighbors won’t recognize him.

So here’s the thing. Red is an omnivore. And though we associate him with pine cones, especially in the winter, he also eats flowers and insects and fungi and even smaller mammals if given the chance. And acorns. And this year is also a mast year for acorns in our neck of the woods.

He’d peeled the outer woody structure away and had started to dine, but again, something or someone, and possibly I was the culprit, had interrupted his feeding frenzy.

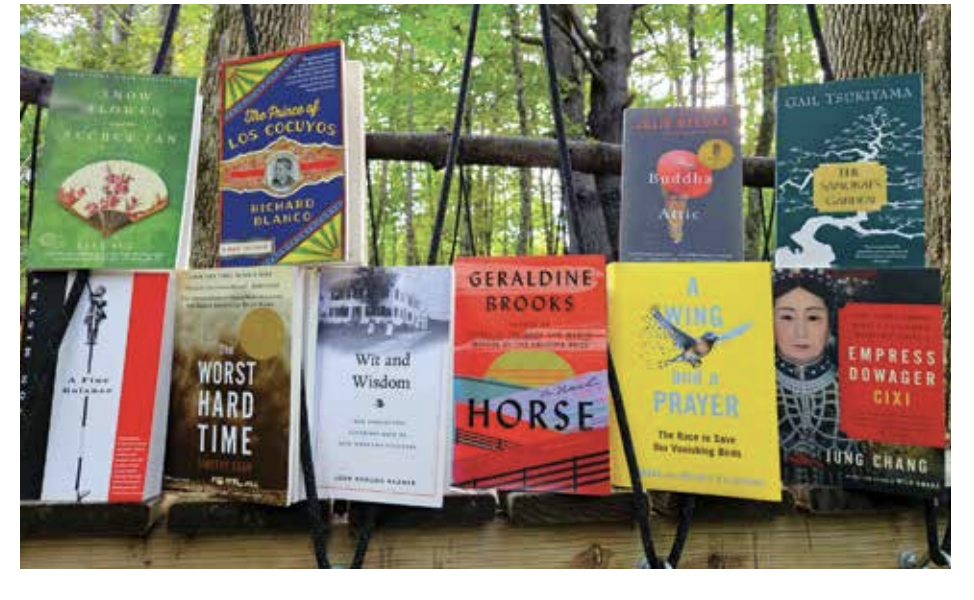

That said, I was delighted to find the acorn shell fragments because already in my collection I had samples from a Gray Squirrel and a Porcupine. Now I have all three and you can see by the tape measure how they compare in size, as well as the manner of stripping. As you can see, Red’s fragments are about a quarter inch in size, while Gray’s a half inch or so, and Porky’s are about three quarters of an inch. And the latter are much more ragged in shape.

Red. My Squirrel Friend. He just doesn’t know it. Maybe by the end of the winter he will because I intend to call upon him frequently to see what else he might teach me.