“Who cooks for you?” was the question I heard being asked as I fell asleep last night. And “Who cooks for you all?” the response I awoke to this morning.

‘Tis the season for owl mating calls, in this case Barred Owls, and therefore the season to promote two books about some species that hoot in our neighborhoods.

The first, The HIDDEN LIVES of OWLS: The Science and Spirit of Nature’s Most Elusive Birds by Leigh Calvez, provides a fun and informative read. Perhaps I like it so much because we share a name and an interest in nature. But really, it’s the stories she tells about her experiences in the night world that make me feel as if I’m sitting on a tree stump or rock wall beside her–waiting and watching. Listening and learning.

Calvez begins her book with silhouettes for eleven owls and a list that includes the scientific name of each, overall length, and wingspan.

The first chapter is about Northern Saw-whet Owls, a new favorite for me since I was honored with the opportunity to meet one at the end of 2017 as I snapped my way through a thicket of hemlock trees, twigs breaking with each movement. Despite all the noise, this owl flew in and our eyes connected. Like Calvez, that sighting quivered in my mind and heart as I tried to remain calm and maintain my focus. I felt like a little kid wearing big girl boots, such was my excitement.

It’s through Calvez that I learned the origin of this bird’s name: the rasping call reminding those who named it of the sound made when “whetting” or sharpening a saw against a file.

And did you know that within mated pairs of these little birds, minute members of the owl family as they aren’t much bigger than a robin, the female sits on the nest for an almost one-month incubation period, while the male dutifully brings food? He actually continues this process even after the young’uns fledge, while momma goes off to the spa in order to regain her strength (or start another brood).

Since she first became fascinated by owls, Calvez had the good fortune to travel to a variety of locations and learn from others–as well as from the owls. She delved into the science of the species and the spirit of some individual birds; her stories are all tucked into this 205-page book. While some are species we may not see in the Northeast, for she writes about those she most familiar with in the Northwest, there’s still plenty to be gained from reading this book.

The book ends with the following: “Notes from the Field: Insights from an Owl.” I wish I could share it with you, but don’t have permission to do so. Let me just say–this list and the silhouettes and comparisons at the beginning make the book well worth the purchase. And the stories in between, filled with wit and wisdom, make it well worth the read.

The second book, which I purchased the same day, is OWLS of the NORTH: a naturalist’s handbook by David Benson.

This book is more of a guide, filled to the brink as it is with photographs and facts about ten owls. For each species, Benson includes a global map and quick list of the following: description, range, size, wingspan, other names, diet, a brief personal story about an experience with the particular owl, identification, sounds, habitat, food, hunting, courtship and nesting, juveniles, and behavior. Almost every page features one or two action shots.

And then there are the sidebars, highlighted within an orange box on each of the odd-numbered pages. One included information about pellets, whitewash and skulls.

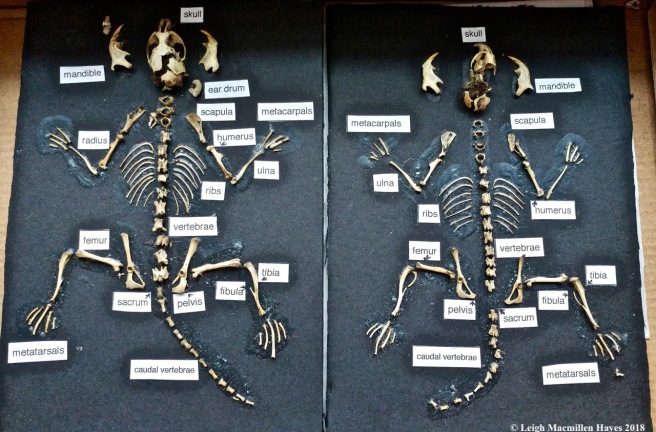

Of course, that reminded me that I have an owl pellet in my collection of all things natural. I found it in March 2016 at Brownfield Bog. According to Benson’s sidebar: “Owls usually swallow their prey whole. An owl catches a mouse, kills it with its talons or by biting its neck and then bolts the whole thing down. Much of the mouse is not very digestible though–the bones, fur and other tough parts don’t provide much nutrition. These are compacted together in the owl’s digestive tract. Then, about six hours after the meal, a pellet of these indigestible parts is coughed up and it drops to the ground beneath where the owl is roosting.”

I’ll probably never dissect the pellet I found, but did dissect one for the Maine Master Naturalist Course–and determined that the owl had consumed two voles. (Don’t look too closely for I know that I put a couple of bones in the wrong place–nobody’s perfect.)

We have an Owl Prowl coming up at the Greater Lovell Land Trust and I’m trying to learn as much as I can. The two books, The HIDDEN LIVES of OWLS by Leigh Calvez and OWLS of the NORTH by David Benson, have proven to be valuable resources. I purchased both at Bridgton Books, an independent book store.

If you want to learn more, I encourage you to check out these books, join us for the Owl Prowl, or step outside–tis mating season and the calls can be heard. You might even think about responding. Go ahead–give a hoot.

The HIDDEN LIVES of OWLS: The Science and Spirit of Nature’s Most Elusive Birds by Leigh Calvez, published 2016, Sasquatch Books.

OWLS of the NORTH: a naturalist’s handbook by David Benson, published 2008, Stone Ridge Press.