As I drove down Heald Pond Road in Lovell today I wasn’t sure what awaited me. But isn’t that the point? Every venture into the great outdoors should begin as a clean slate and it’s best not to arrive at the trailhead with expectations.

And so I didn’t. Well, sorta. I really wanted to see a porcupine. And maybe an otter. And definitely an owl. But I knew better and so I passed the last barn on the road and then backed up and stepped out, captivated by the colors in the scene before me.

A few minutes later, I strapped on my snowshoes and headed up the trail. My plan–to climb to the summit of Flat Hill at the Greater Lovell Land Trust’s Heald and Bradley Ponds Reserve and then circle around Perky’s Path upon my return.

Breaking trail was my job in the rather deep snow given recent storms, but easy to move upon and so I sashayed up. What surprised me, however, was the lack of tracks left behind by the mammals that I know live in these woods.

I did stop at the balsam firs decorated by a local 4-H club in December as part of the Maine Christmas Tree Hunt. The dangling pinecones once sported peanut butter and birdseed, but today that was all a memory so I knew birds and deer had stopped by in the last few months.

And then, as I neared the flat summit, I found tracks of a mammal that had checked out the base of every tree and under every downed limb. In fact, as I soon realized, it was more than one mammal that I followed as I went off trail. Bobcats. Indeed. Though typically solitary, these two traveled together. It is mating season and males and females will travel together during courtship.

Though the prints were difficult to photograph given the glare, by the toes, ridge and overall shape, I knew them.

And scat! Filled with white hair. I have close-up views should you choose a closer look, but chose to give those who find scat to be rather disgusting a break. 😉

And then I found another set of tracks and knew that besides squirrels and little brown things, the bobcats were also searching for a bigger dinner. On the left–a porcupine trough, and on the right, the bobcat trail.

Ever since I’ve traveled this trail, I’ve seen the work of the porcupines at the summit. And sometimes I even get to see the creator. In winter, porcupines eat needles and the bark of trees, including hemlocks, birch, beech, aspen, oak, willow, spruce, fir and pine. And they leave behind a variety of patterns.

If I didn’t know better, I could have been convinced that this ragged work was left behind by a chiseling woodpecker, but it, too, was porcupine work.

All about the summit, recent chews were easily identified for the inner bark was brighter than the rest of the landscape. And below these trees–no bark chips such as a beaver would leave, for the porcupine consumed all the wood.

While snow flurries fluttered around me, the summit view was limited and it looked like the mountains were receiving more of the white stuff. (Never fear–we’ll get more as our third Nor’easter in two weeks or so is expected in two more days. Such is March in Maine.)

From the summit, rather than follow the trail down, I tracked the bobcats for a while, first to the north and then to the south. I had hoped to find a kill site, but no such luck. Instead, the writing on the page was found upon the pines where script lichen, a crustose, was located between the lines of bark scales.

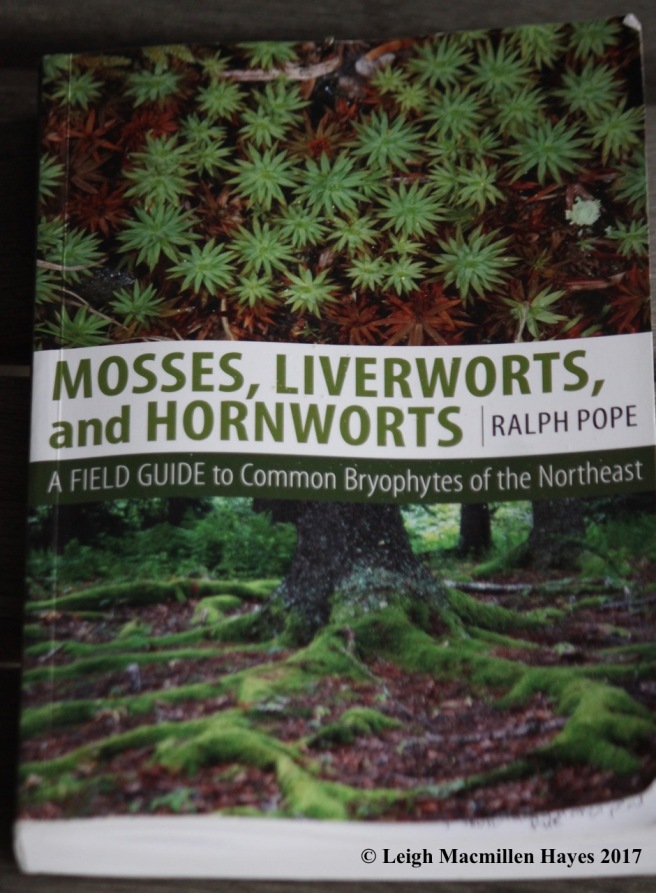

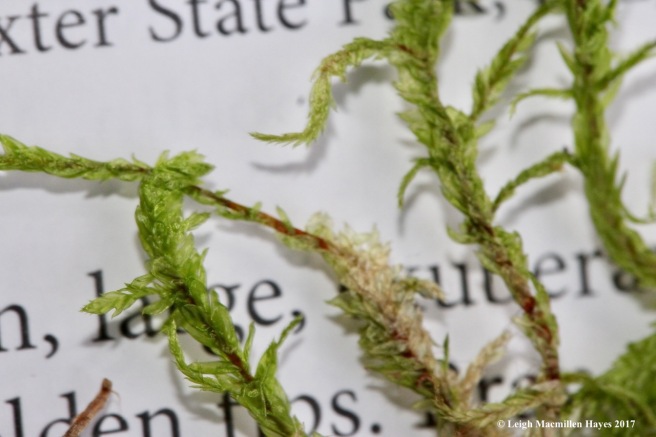

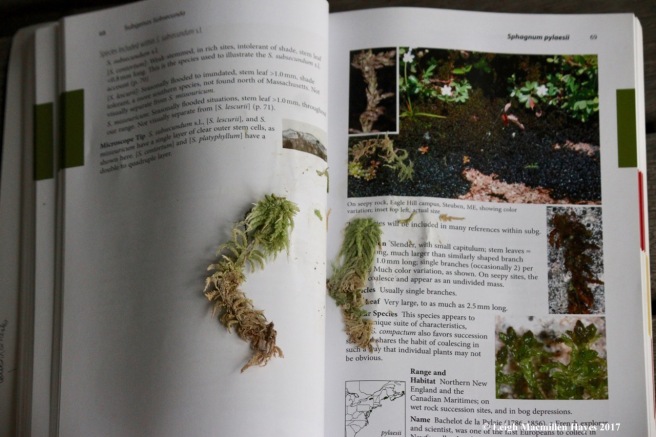

I also found plenty of Frullania, that reddish brown liverwort that graced so many trees. And among it, a moss I’ll simply call an Ulota. As I looked in Ralph Pope’s book, Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts , upon arriving home, I realized I should have paid attention to capsules for that would have helped me determine whether what I saw was Ulota crispa or Ulota coarctata. Another lesson for another day.

At last I reached Perky’s Path, which may not seem like a major feat if you’ve been there, but actually I’d explored off trail for quite a ways and it took me a while to get down to the wetland.

And because I was in the wetland, maleberry shrubs bordered the edge and showed off their bright red buds and woody, star-shaped seedpods.

After focusing on them for a while, I looked down at the snow’s surface and the most subtle of prints appeared before my eyes. My two bobcats. The curious thing–at the summit the mammals had sunk into the snow and the prints were a bit difficult to decipher. I assumed those summit impressions had been made about two days ago. But on the wetland, the bobcats walked atop the snow–when conditions were firmer and I suspected they’d been created last night.

I followed the edge of the wetland to the bridges that cross a brook that forms at the outlet of Bradley Pond, constantly on the lookout for the bobcat tracks again.

And I found them! Beside the brook.

What had they found on the wetland, I wondered?

Continuing on, I found that they’d checked on the woodwork left behind by another critter of these woods who had also moved about last night.

Beaver works. And their piles of woodchips. Unlike a porcupine, a beaver doesn’t eat the chips. Rather, it cuts down a tree for food or a building material. The chips are like a squirrel’s midden of cone scales–the garbage pile of sorts.

I noted where the beaver had moved into the brook . . .

And left some sticks behind. For future food? Future building? Stay tuned.

Typically in other seasons I can’t move beside the edge of the brook, but today I could. The lighting kept changing and water reflected the sky’s mood.

And because I was by the water, I kept noting small insects flying about–almost in a sideways manner. Then I found some on the snow–a member of the Diamesa species, a midge I believe. And do you see the small black speck below it–a snowflea, aka spring tail.

And do you see the two little nobs on the fly’s back, the red arrow pointing to one? Those are the haltere: the balancing organ of a two-winged fly; a pair of knobbed filaments that take the place of the hind wings.

Eventually, I followed the eastern edge of the wetland back to my truck, wondering if there was any more action but found none. In fact, the water was low so I knew the beaver works weren’t to rebuild the dam. Yet. Nor did I find any more bobcat tracks. But I’d found enough. And I think I know some of what the bobcat knows.

You must be logged in to post a comment.