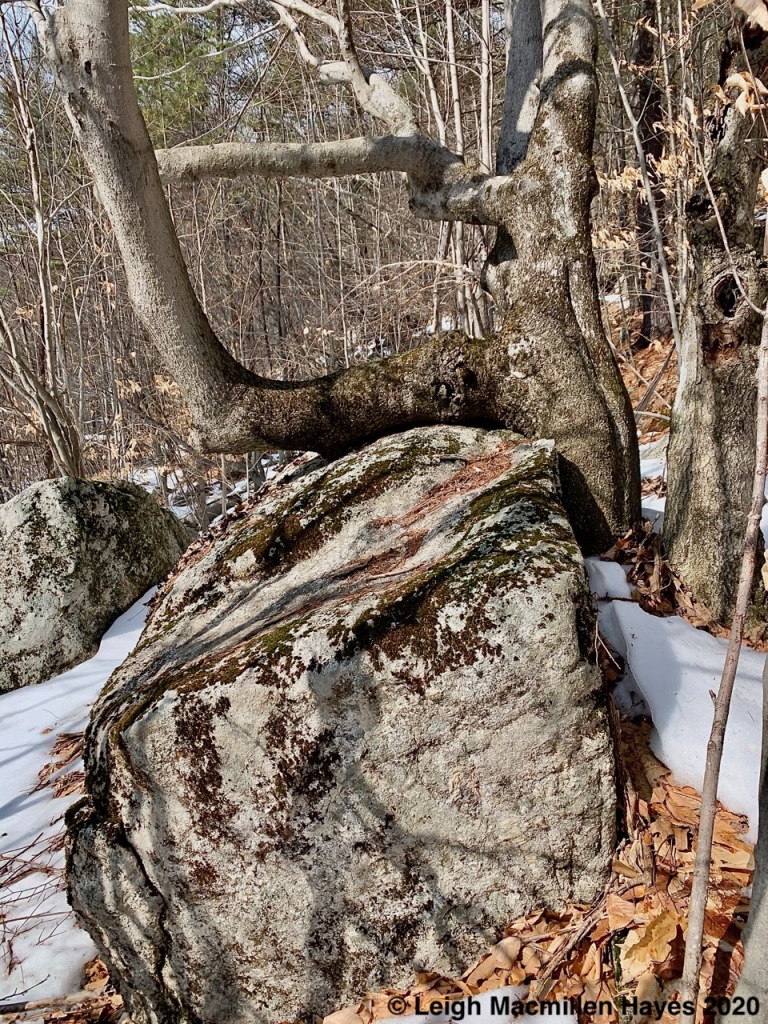

From sun to rain to sleet and even snow, it’s been a weekend of weather events. And like so many across the globe, I’m spending lots of time outdoors, in the midst of warm rays and raw mists.

I’m fortunate in that I live in a spot where the great beyond is just that–great . . . and beyond most people’s reach. By the same token, it’s the most crowded place on Earth right now.

On sunny days, water scavenger beetles swim about in search of a meal to suit their omnivorous appetite.

Preferring decaying plant and other organic matter as the ideal dinner menu are the mayfly larvae. Some call them nymphs, others know them as naiads.

To spot them, one must really focus for they are quite small and blend in well with the bottom debris, but suddenly, they are everywhere.

And then, another enters the scene, this possibly one of the flat-headed mayflies. If you look closely, you may see three naiads, two smaller to the upper far left and lower on the stick to the right. In between is the larger, its paired gills and three tails or caudal filaments easier to spy because of its size.

Switching to a different locale, a winter stonefly, its clear wings handsomely veined, ascends fallen vegetation on its tippy toes and my heart dances for this is probably my last chance to see one of these aquatic insects until next year. Then again, none of us can predict the future.

In the mix, green insects move and I surmise by their minute size, shape and coloration that they are leafhoppers all set to suck sap from grasses, shrubs, and trees.

Who else might live here? Why a caddisfly larva in its DIY case.

Of course, no aquatic exploration is complete without sighting mosquito larvae somersaulting through the water.

And a wee bit away from the watery spots, the pupal stage of a ladybug, a form that has perplexed me for months. It is my understanding that motion stops and so does feeding, the insect scrunches up its body and color changes . . . but the transition should last five to seven days–not since last fall. Or perhaps this species has a lot to teach me about waiting and what is to come.

Another one for the books is a translucent green caterpillar not much more than inch-worm size that I discover clinging to a red maple twig only hours before snow descends upon the setting.

Mind you, I also spotted three crescent or checkerspot butterflies, their small orange and black wings adding a quick flash of color as they flutter across my path.

And then my mind shifts, as it has a lot in the last few weeks, and between patches of snow and a fresh snow fall, I welcome the opportunity to remember others who share this space, including an opossum amidst the turkeys and deer.

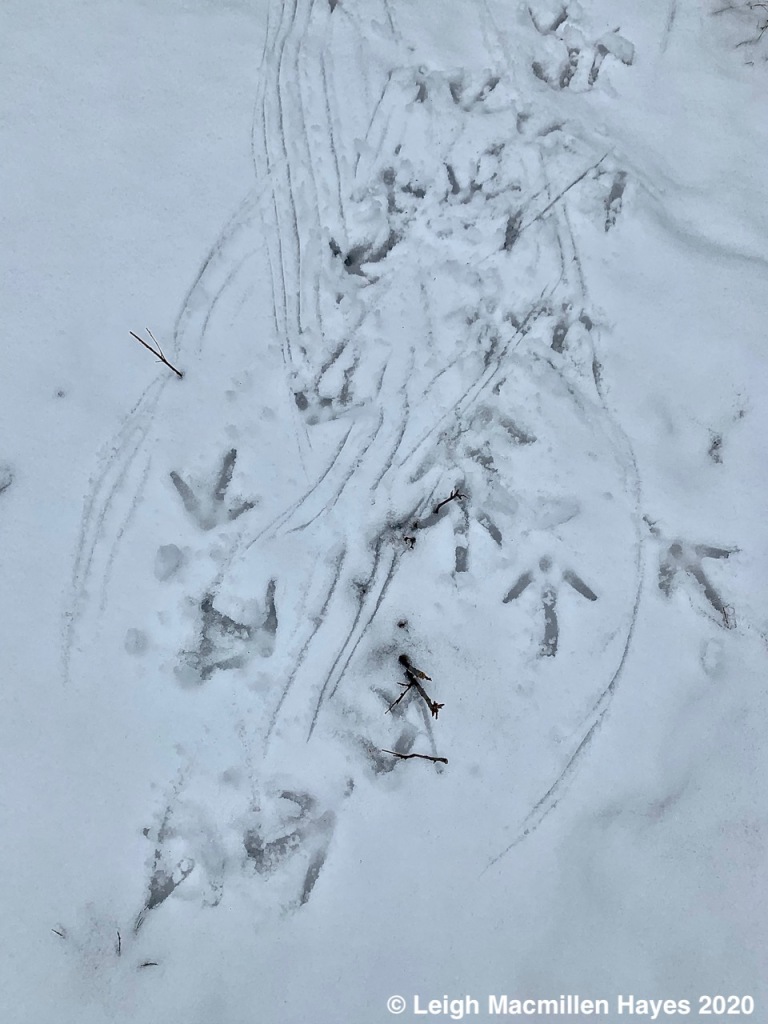

Following a Tom turkey who seemed to walk with determined speed, I get to meet another neighbor and note by Tom’s toe print that his path intersected with that of a coyote after the predator had passed by. Phew for the Tom.

After all, he has a job to do. Suddenly, I note a change in his pace, which slows down considerably based on the closeness of his feet. And then I spy wing marks on the outer sides of the prints and know that he is in display mode. The curious thing: on average, he takes ten steps, then displays, takes ten steps, then displays. I know this because I counted, over and over again. But then . . . he must hear his lady friends for he makes an about turn.

And struts his stuff.

I’m not sure they are impressed for they move on and head in the direction of other neighbors, specifically a squirrel and porcupine. Others presenting tracks include chipmunks, snow lobsters, I mean snowshoe hares, moose, and a bobcat.

This is my little space on the Earth and I love spending time trying to understand it and find out more about my neighbors.

Watching over all of this action is a Fox Sparrow, whom I greet as a welcome visitor, knowing he’s on his way north to the boreal forest.

Like him, we’re all in transition, my neighbors and me. What the future holds, we know not. The best we can do is hope we come out on the other side–changed by the experience, of course.

You must be logged in to post a comment.