I’m a wanderer both on and off trail, and sometimes the path has been macadamized. Such was my following this morning as I paused on the way home from running an errand in North Conway, New Hampshire.

I’d stuck to the backroads on my way out of state to avoid road construction on Route 302, but knew that upon my return I wanted to stretch my legs along the Mountain Division Trail in Fryeburg.

The delightful four-mile rail trail, so named for the railroad line it parallels, intended for walkers, runners, bikers, roller bladers, etc., extends from the Maine Visitors Center on Route 302 to the Eastern Slope Airport on Route 5 and can be accessed from either end or several points between.

The wind was blowing and the bug count low, so though it wasn’t a warm, sunny spring day, it was a purely enjoyable one. And the cheery cherry flowers enhanced the feeling.

All along the way, it seemed, the Red Maples had not only leafed out, but yesterday’s flowers had magically transformed into today’s samaras that dripped below like chandeliers.

Lovely tunes and chips were also part of the landscape and I have no idea if I’ve identified this species correctly, but I’m stepping out on a branch and calling it an Alder Flycatcher. I’m sure those who know better will correct me. The naming isn’t always necessary, however. Sometimes, it’s more important to appreciate the sighting, the coloration, and the sound. For this bird, it was the dull olive green on its back that caught my attention.

And then up above on the other side of the track, it was the “Cheery, Cheery, Cheerio” song that helped me locate the American Robin in another maple raining with seeds.

Maples weren’t the only trees showing off their flowers, and those on the Northern Red Oaks reminded me of grass hula skirts below Hawaiian-themed shirts.

Even the ordinary seemed extraordinary like the Dandelion. Each ray of sunshine was notched with five “teeth” representing a petal that formed a single floret. Fully open, the bloom was a composite of numerous florets.

Nearby, its cousin, the early blooming Coltsfoot, already had the future on its mind and little bits of fluff blew in the breeze.

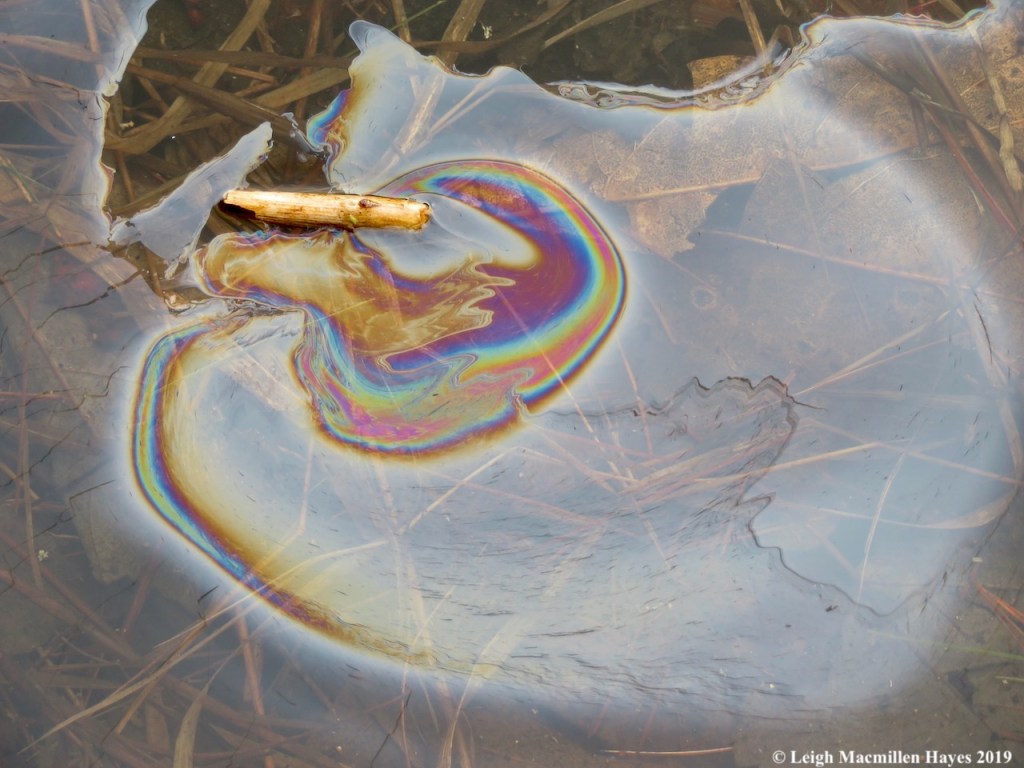

Eventually, I reached Ward’s Pond and after scanning the water found a Painted Turtle seeking warmth. The day was overcast and there was a bit of a chill in the strong breeze. Being down below the trail, at least the turtle was out of the wind and I had to assume that the temperature was a bit higher than where I stood.

This is a trail that may look monotonous, but with every step there’s something different to see like a Pitch Pine showing off three generations of prickly cones. What was, is, and shall be all at the tip of the branch.

It seemed like every time I looked to the left, such as at the pine, a sound on the other side of the trail caught my attention. And so it was that I realized a White-tailed Deer was feeding on grasses behind a fence by a now-defunct factory (so defunct that the roof had collapsed under the weight of snow). Notice her ears.

And now look at her again. A deer’s ears are like radar and she can hone in on a sound by turning them.

I don’t know if she was listening to me or to the Eastern Towhee telling us to drink our tea.

After 2.5 miles, I decided to save the rest for another day and follow the path back. Though loop trips are fun, following the same path back brings new sights to mind, like the Interrupted Fern I’d walk past only a few minutes before. Notice its clump formation known in the fern world as vase-like.

And the butterfly wings of its interrupting leaflets covered with sporangia. My wonder came with the realization that within the interruption not all of the pinnules or subleaflets were covered with the bead-like shapes of fertility. Spores stored within essentially perform the same function as a seed: reproduce and perpetuate the species. So–is part of the pinnule fertile while the rest remains sterile? Do I need to check back? Oh drats, another trip to make along the Mountain Division Trail. Any excuse to revisit it works for me, though one hardly needs an excuse.

Further along I looked to the other side of the tracks for I’d spotted bird movement. Behind it was the reason–my White-tailed Deer friend. I have a feeling people feed it for it seemed not at all disturbed by my presence, unlike the ones in our yard and the field beyond that hear my every move within the house even in the middle of winter and are easily spooked.

The deer, however, wasn’t the only wildlife on or near the trail. Suddenly, a Red Fox appeared and we each considered the other. He blinked first during our stare down and trotted away.

Passing by Ward’s Pond once again, I stopped to check on the turtle. It was still in the same spot I’d seen it probably a half hour before.

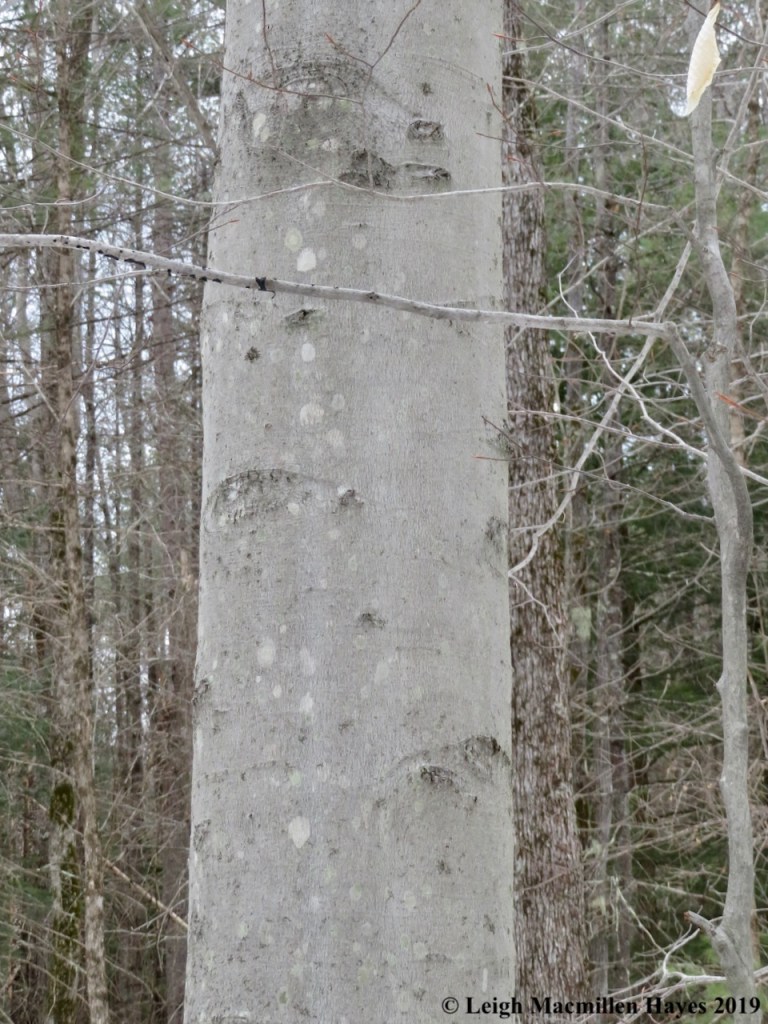

Not far from the visitors center, a Big-Toothed Aspens chose to be examined for the soft downy feel as well as color of its leaves. The various hues of color in leaves during spring is caused by the presence of pigments called anthocyanins or carbohydrates that are dissolved in the cell sap and mask the chlorophyll. As the temperature rises and light intensity increases, red pigment forms and acts as a sunscreen to protect the young leaves from an increase in ultraviolet rays.

Because I was standing still and admiring the leaves, I heard another bird song and eventually focused in on the creator.

And so I have the Big-Toothed Aspen to thank for showing me the Indigo Bunting. My first ever. (Happy Birthday Becky Thompson.)

A turtle. A deer. A fox. A towhee. A bunting. All of that was only a smattering of wonder found along the Mountain Division Trail. If you go, make sure you recall the old railroad signs: Stop, Look, and Listen.