Maybe it’s my teacher blood. Maybe it’s just because I love sharing the trail with others who want to know. Maybe it’s because I realize how much I don’t know, but love the process of figuring things out.

Whatever it is, I had the joy of sharing the trail with this delightful young woman who kept pulling her phone out to take photographs and notebook out to jot down notes about our finds along the trail, that is . . . when her fingers weren’t frozen for such was today’s temperature.

Among our great finds, a Red-belted Polypore capped with a winter hat as is the custom this week.

I was really excited about our opportunity to share the trail for I wanted to learn more about her work with Western Foothills Land Trust and Loon Echo Land Trust, and her roll as the Sebago Clean Waters Conservation Coordinator.

But, I was also excited to walk among White Cedars for though I was only twenty minutes from home, I felt like I was in a completely different community. Um . . . I was.

Shreddy and fibrous, the bark appeared as vertical strips.

We paused beside one of the trees where a large burl that could have served as a tree spirit’s craggy old face, begged to be noticed. We wondered about what caused the tree’s hormones to create such a switch from straight grains to twisted and turned. Obviously some sort of stress was involved, but we couldn’t determine if it occurred because of a virus, fungus, injury, or insect infestation.

And then there were the leaves to focus in on for their presentation was like no other. (Unless it’s another cedar species, that is.) I loved the overlapping scales that gave it a braided look. And if turned right side up, it might have passed as a miniature tree or even a fern.

Lungwort Lichen drew our attention next. My ever-curious companion asked if it was tree specific. Found in humid forested areas, this lichen grows on both conifers and hardwood trees.

Having found the lichen, I knew it was time for a magic trick and so out of my mini-pack came a water bottle. Within seconds, the grayish color turned bright green due to its algal component. It’s an indicator for rich, healthy ecosystems such as old growth forests.

Where the water didn’t drip, it retained its grayish-green tone, and the contrast stood out. Curiously, snow sat atop some of the lichen’s structure, and one might have thought that all the lettuce-like leaves would have the brighter appearance, but today’s cold temp kept the snow from melting and coloration from changing.

Our next great find: a reddish-brown liverwort known as Frullania. It doesn’t have a common name, and truth be known, I can never remember if the dense mat is asagrayana or its counterpart: eboracensis.

Three dimensional in form, it reminded me of a snarl of worms vying for the same food. Oh, and the dense form: asagrayana in case you wondered.

Over and over again as we walked, we kept looking at the variety of trees and my companion indicated an interest in learning about them by their winter presentation, including the bark. I reminded her that once she has a species in mind, she needs to use a mnemonic that she’ll remember, not necessarily one that I might share. In this case, I saw diamonds in the pattern, and sometimes cantaloupe rind. Others see the letter A for Ash, such as it was. She saw ski trails. The important thing was that we both knew to poke our finger nails into its corky bark. And that its twigs had an opposite orientation.

One of the other idiosyncrasies we studied occurred on the ridges of Eastern White Pines, where horizontal lines appeared as the paper my companion jotted notes upon. It’s the little things that help in ID.

Sadly, our time had to end early as she needed to return to the office, but I decided to complete the loop trail and see what else the trail might offer.

Vicariously, I took her along, for so many things presented themselves and I knew she’d either be curious or add to my understandings. Along a boardwalk I tramped and upon another cedar was a snow-covered burl.

A wee bit further, and yet another peeked out from between two trunks, stacked as it was like a bunch of cinnamon buns. Curiously, the center bun formed a heart. Do you see it?

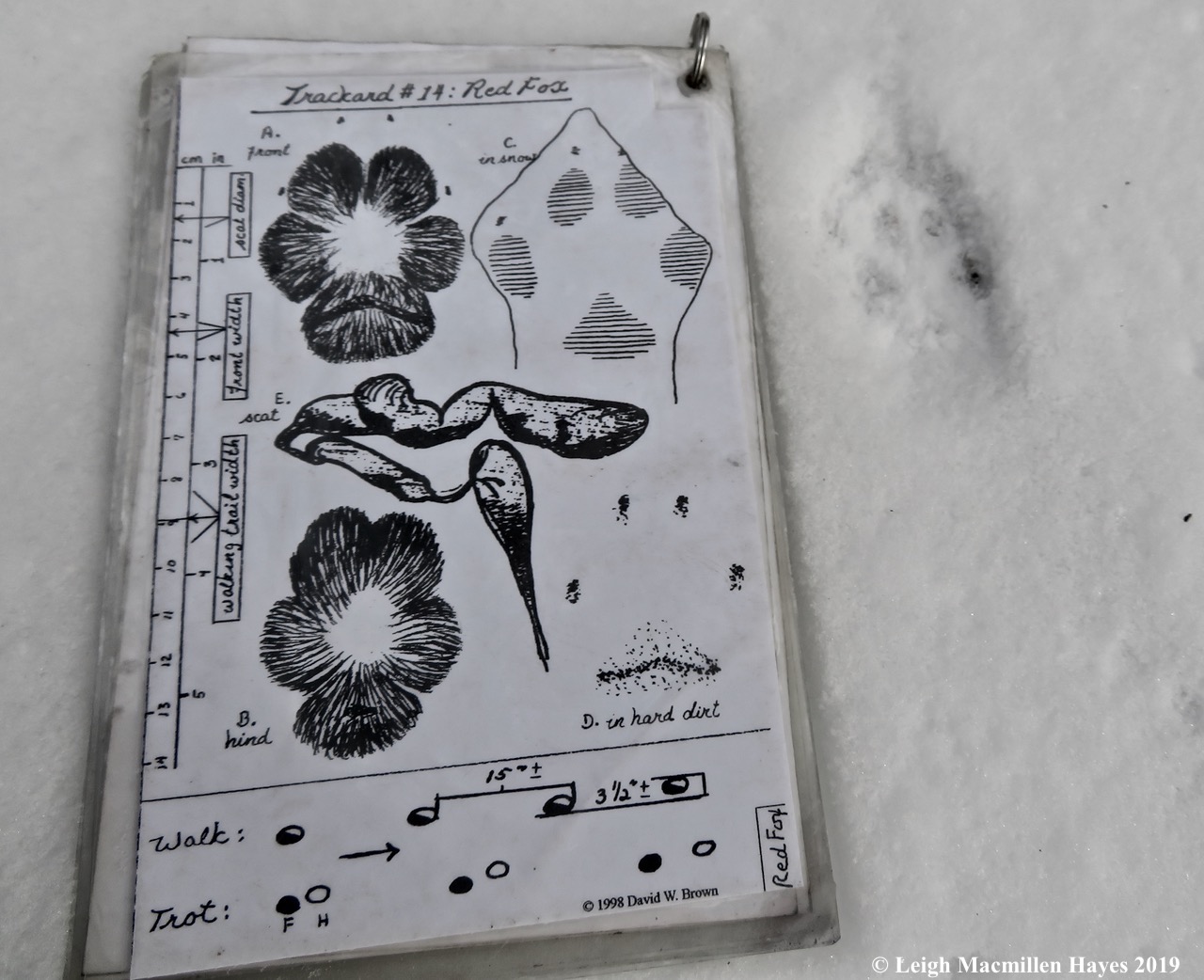

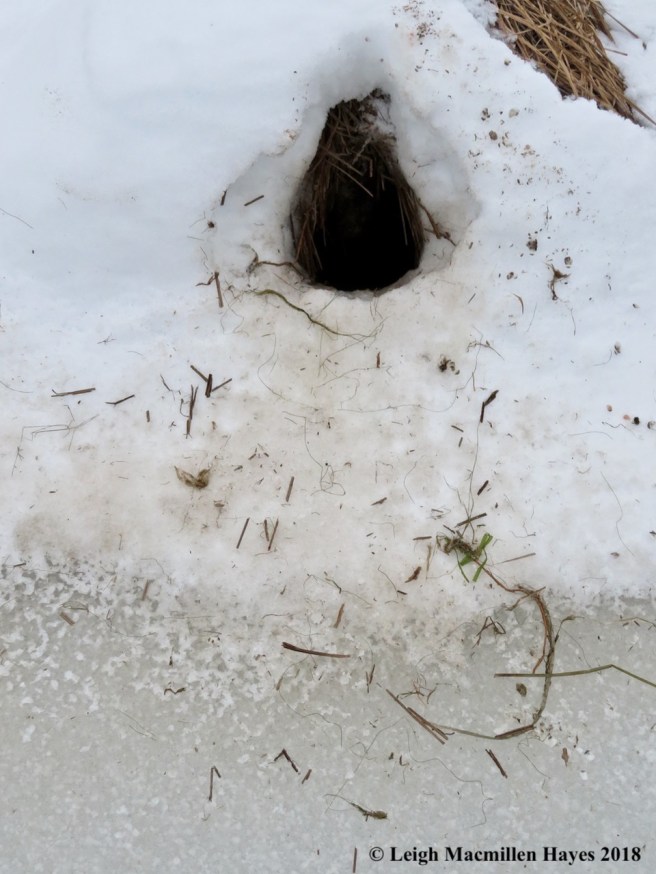

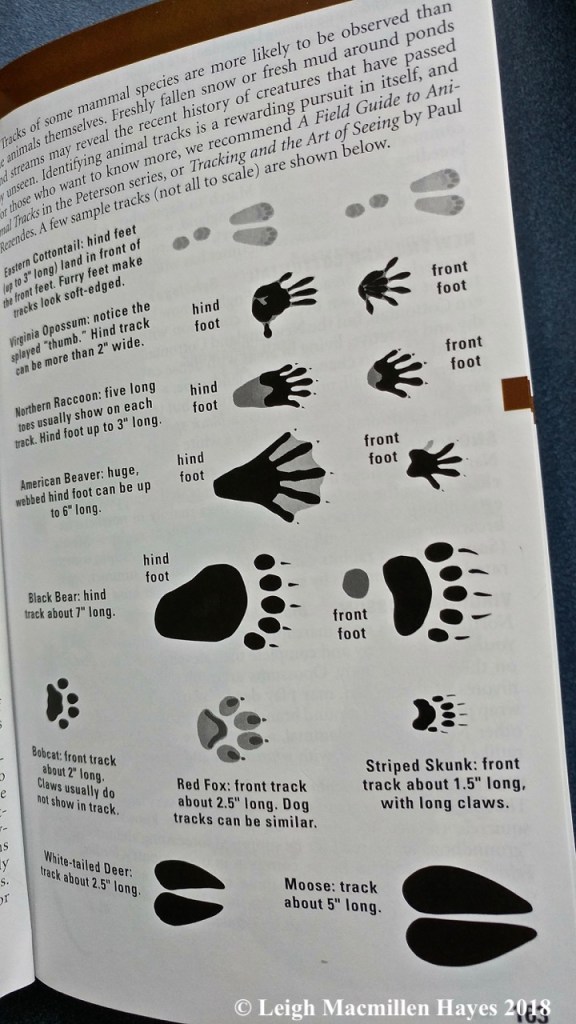

It was upon this trail that I began to see more than the bark of trees. At my feet, tracks indicated that not only had a few humans walked the path, but so had mammals crossed it. And one of my first finds was the illustrious snow lobster, aka Snowshoe Hare.

It had tamped the snow down among some greens and I knew it was time to stoop for a closer look.

Each piece of vegetation that had been cut, had been cut diagonally–Snowshoe hare-style, that is.

Moving along, some winter weeds presented themselves as former asters and others, but my favorites were the capsules of Indian Tobacco.

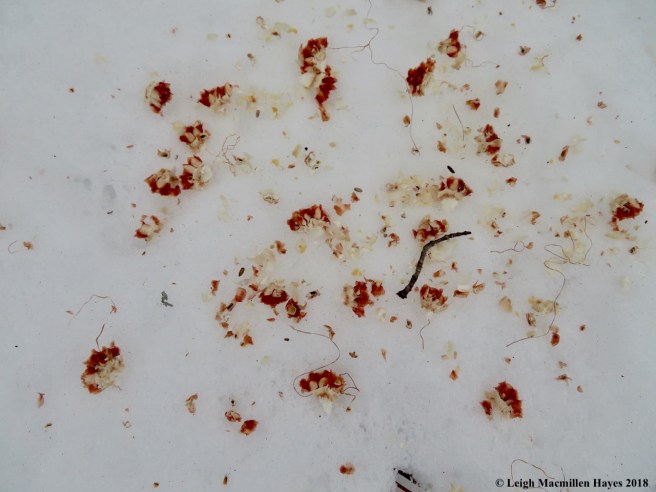

In my book of life, one can have more than one favorite, and so I rejoiced each time I saw a birch catkin upon the snow carpet, its fleur di lis scales and tiny seeds spread out. The seeds always remind me of tiny insects, their main structure featuring a dark body with translucent wings to carry it in a breeze, unless it drops right below its parent and takes up residence in that locale.

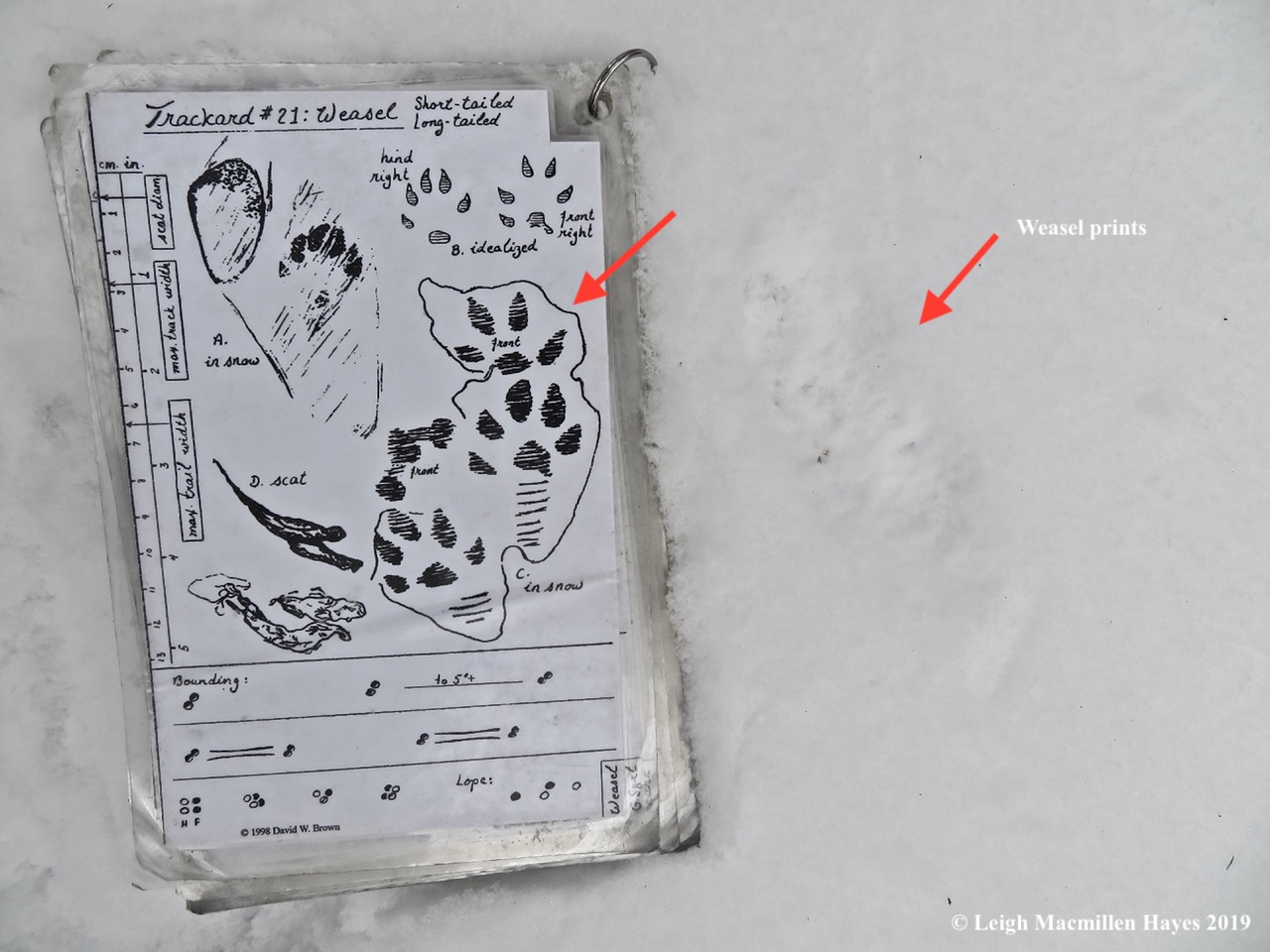

Further along, scrawled scratching in the snow and leaves indicated another mammal lived in the woodland, conserved as it was by Western Foothills Land Trust. With this sight, my mind stretched to the fact that a corridor had been created and the more I followed the trail, the more I realized others crossed over it because this was their home. And they were still at home here.

The scratcher had left a signature in its prints.

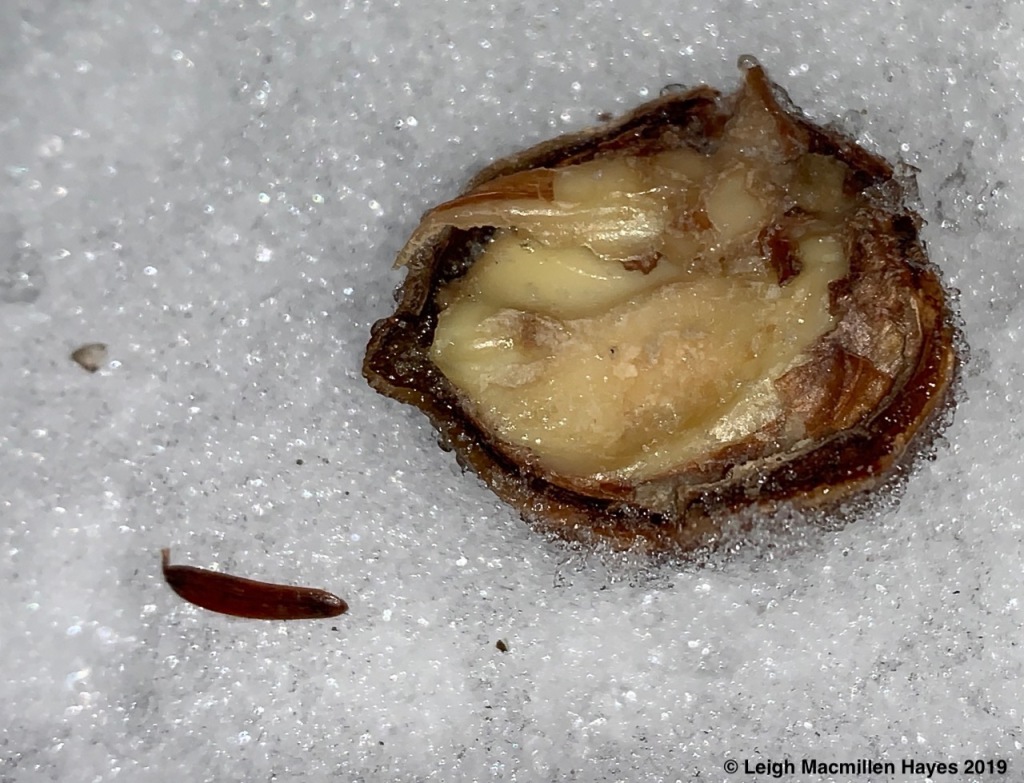

And the source of its food: fallen nuts that about a month ago rained down like the sky was falling. Northern Red Oak Acorns. This one had been half consumed by a White-tailed Deer.

While traveling earlier with my companion, we’d talked about the tree that produced the deer food, but it wasn’t till I followed the loop that I found it. To me, the ridges of the Northern Red Oak looked like ski trails, with a reddish tinge in the furrows.

Oh, and that deer; it seemed to have dined on the bark of a Red Maple in the recent past–probably as recent as last winter or spring.

After a three hour tour, I delighted in traveling the Half Witt Trail three times (out and back with my companion and then again as I completed the loop) and Witt’s End.

They are new additions to Western Foothills Witt Swamp & Shepard’s Farm Preserve, and the journey . . . ah the journey.

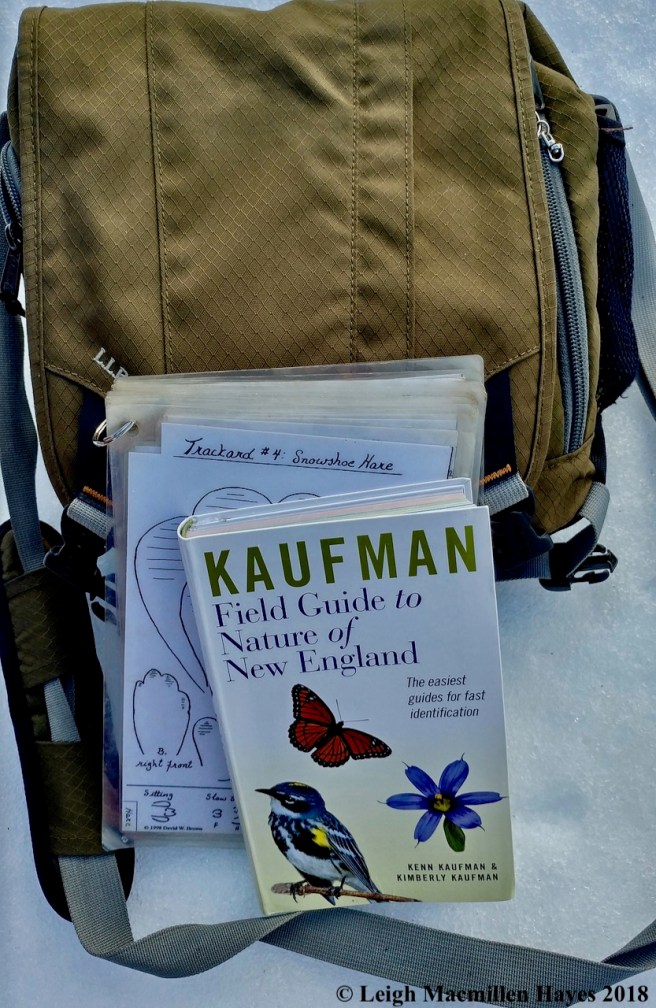

Along the way, this young woman wanted to know what questions to ask and where to seek answers. I helped as much as I could, but noted that there are others who understand much more than I do.

Thank you, Hadley Couraud, for today’s journey. When it’s shared either actually or virtually with one who has a desire to learn, it’s always special.