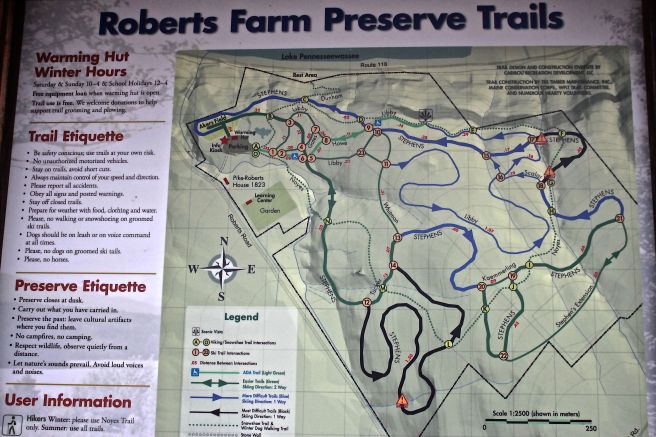

My original intention when I set out this morning was to snowshoe from the Gallie parking lot on Route 5, follow the Homestead Trail and then connect with the Hemlock Trail as I climbed to the summit of Whiting Hill. I planned to make it a loop by descending via the red trail back to the green Gallie Trail.

Not to be as the parking lot hadn’t been cleared yet of yesterday’s Nor’easter, which dumped several inches of snow, sleet and freezing rain upon the earth. When Plan A fails, resort to Plan B. A drive down Slab City Road revealed that the Fairburn parking lot wasn’t yet cleared either, but the boat launch was open (because the pond serves as a water source for the fire department) so I parked there and headed to the trailhead beside Mill Brook. The sight of so much water flowing forth was welcome, especially considering it was a mere trickle a few months ago.

The layers of snow overhanging the brook told the story of our winter. And it’s not over yet–at least I hope it isn’t. We’re in the midst of a thaw, but let’s hope more of the white stuff continues to fall. We need it on many levels, including ecologically and economically.

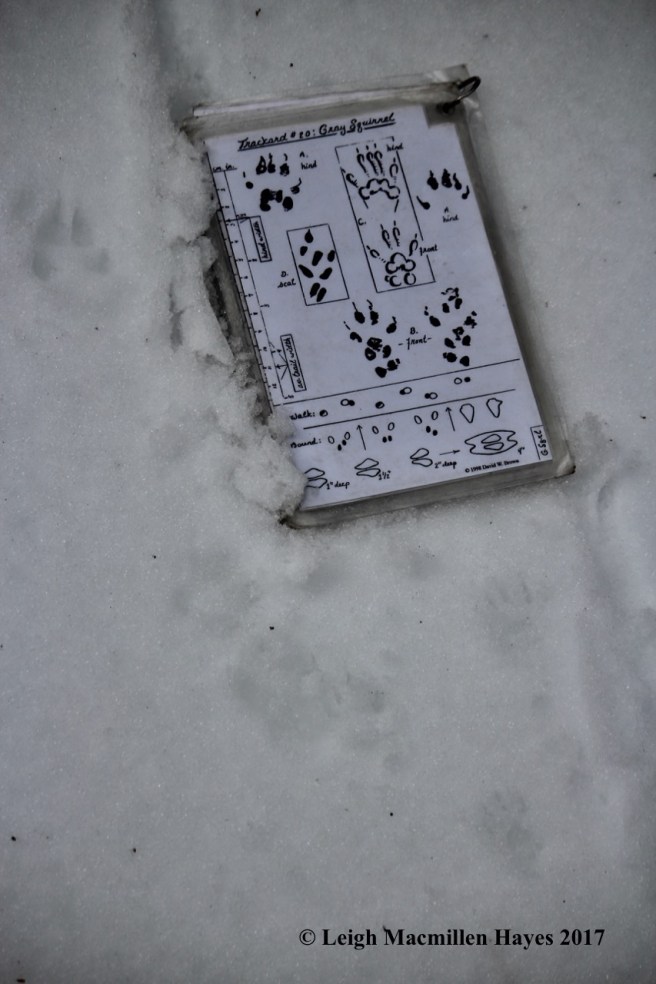

Because of the storm, I thought I wouldn’t see any tracks, but from the very beginning a red fox crossed back and forth between the pond’s edge and higher elevations.

While it may be difficult to discern, a gray squirrel, the four prints with long toes below the Trackards, had leaped up the hill, perhaps after the fox. Lucky squirrel. The fox prints can be viewed to the left of the cards.

My new plan was to follow the red/blue trail to the summit of Whiting Hill. And along the way, a side trip to the vernal pool. Visions of fairy shrimp swam in my head. No, I wasn’t rushing the season, just remembering a fun time pond dipping last spring.

Back on the red/blue trail, I noted that most of the recent seed litter was covered by yesterday’s storm. The Fringed Wrinkle Lichen, however, did decorate the snow. Tuckermanopsis americana, as it’s formally known, grows on twigs and branches of our conifers and birches and often ends up on the forest floor.

It’s a foliose lichen that was named for Edward Tuckerman, of Tuckerman’s Ravine fame on Mount Washington. According to Lichens of the North Woods author Joe Walewski, Tuckerman was “the pre-eminent founder and promoter of lichenology in North America.As a botanist and professor in Boston, he did most of his plant studies on Mount Washington and in the White Mountains.”

Further along, I saw some pileated woodpecker scat about twenty feet from the tree it had hammered in an attempt to seek food. It made me realize that even when I don’t find scat in the wood chips below the tree, I should seek further.

The holes weren’t big–yet.

But the scat–oh my. It looked as if insects were trying to escape the small cylindrical package coated in uric acid.

The trail turned right and so did I, beginning the climb. For most, the ascension doesn’t take more than five or ten minutes. Um . . . at least 45 on my clock today. There was too much to see, including the mossy maple fungi hiding in a tree cavity.

And then I saw something I’d looked for recently after seeing it on the blog Naturally Curious with Mary Holland. Notice how the pine needles are clumped together?

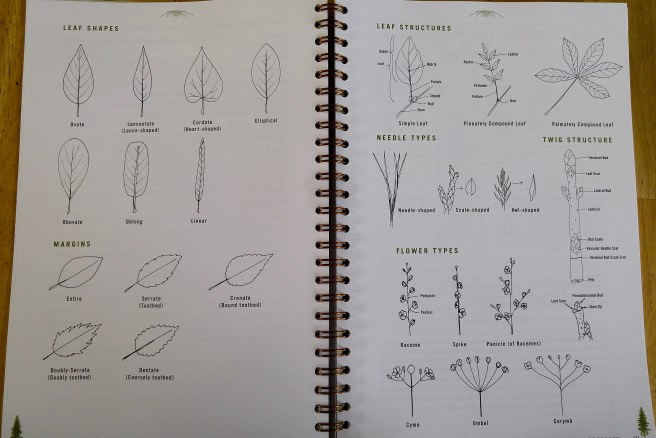

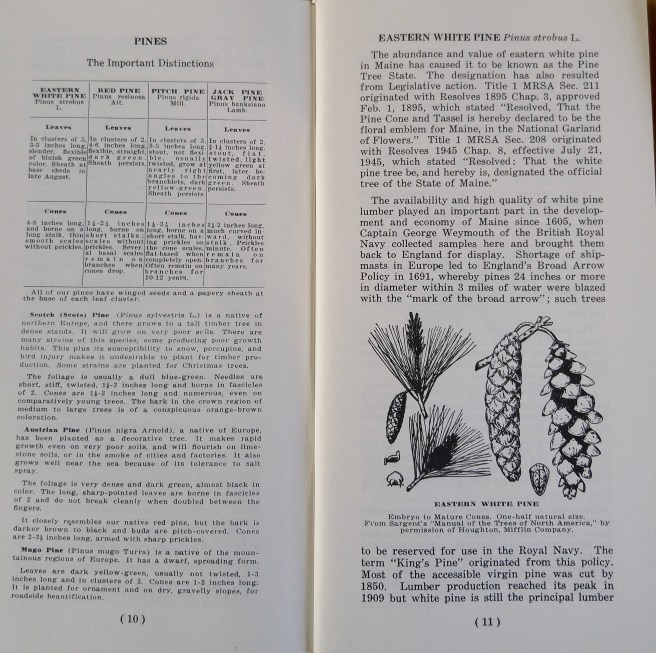

Eastern White Pine needles grow in bundles of five (W-H-I-T-E or M-A-I-N-E for our state tree), but the clumps consisted of a bunch of needles from several different bundles.

What I learned from Ms. Holland is that these are tubes or tunnels created by the Pine Tube Moth. Last summer, larvae hatched from eggs deposited on the needles. They used silk to bind the needles together, thus forming a hollow tube. Notice the browned tips–that’s due to the larvae feeding on them. Eventually the overwintering larvae will pupate within the tube and in April when I come back to check on the vernal pool, I need to remember to pay attention, for that’s when they’ll emerge. Two generations occur each year and those that overwinter are the second generation. The good news, says Holland, is that “Pine Tube Moths are not considered a significant pest.” I only found the tubes on two young trees, but suspect there are more to be seen.

And a few steps later–an old beak. I couldn’t believe my luck. It was then that I realized if I’d been able to stick with the original plan I would have missed these gems. Oh, I probably would have found others, but these were in front of me and I was rejoicing. Inside that bristly tan husk was the protein-rich nut of a Beaked Hazelnut overlooked by red squirrels and chipmunks, ruffed grouse, woodpeckers, blue jays and humans.

Catkins on all of the branches spoke of the future and offered yet another reason to pause along this trail on repeated visits.

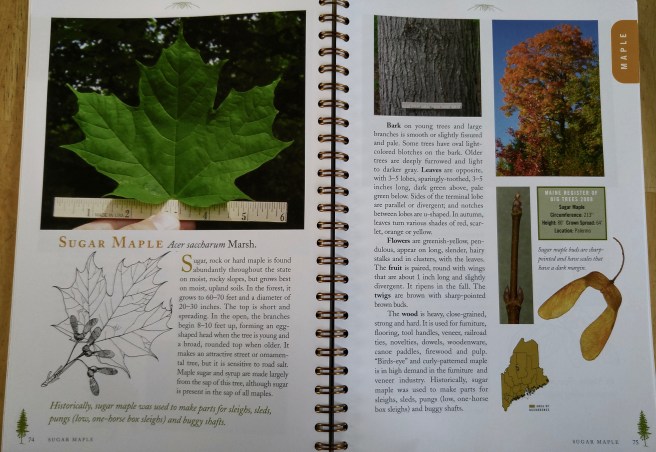

With my eyes in constant scan mode, I looked for other anomalies. One of my favorites was the burl that wrapped around a Sugar Maple. If I didn’t know better, it would have been easy to think this was a porcupine or two.

About two thirds of the way up, there was no rest for the wary, for the bench that offered a chance to pause was almost completely buried.

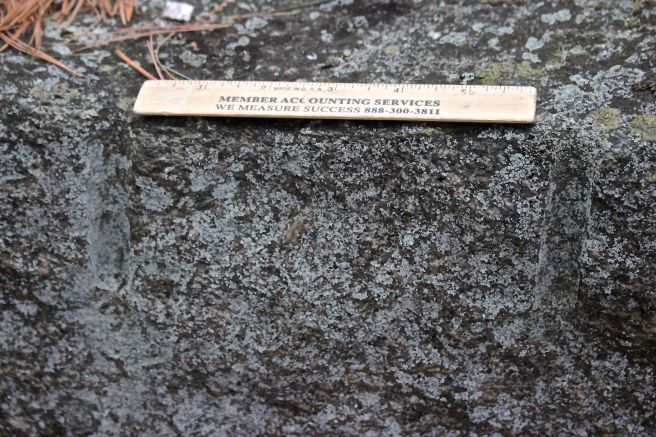

Closer to the summit, the ledge boulders were decorated with snow, Common Polypody ferns and lichens, including Common Rock Tripe, its greenish hue reflecting yesterday’s precipitation.

And suddenly, the summit and its westward view, Kezar Lake in the foreground and Mount Kearsarge showing its pointed peak in the back.

As I’d hiked along the red/blue trail, I noted that the red fox had crossed several times. At the other end of the summit, I checked on the bench where on our First Day 2017 hike for the Greater Lovell Land Trust, we’d discovered the remains of a red squirrel. Today, fox tracks paused in front of the bench before moving on and I had to wonder if had been the one to use this spot as a sacrificial altar.

Finally, it was time to head down. My choice was to follow the red trail toward the Gallie Trail. I love this section because it features some of my favorite bear trees.

The fox tracks continued to cross frequently and so I paused often. And sniffed as well. What I smelled was a musky cat-like scent that I’ve associated with bobcats in the past. What I heard–dried beech leaves rattling in the breeze. They always make me think something is on the move. Ever hopeful I am.

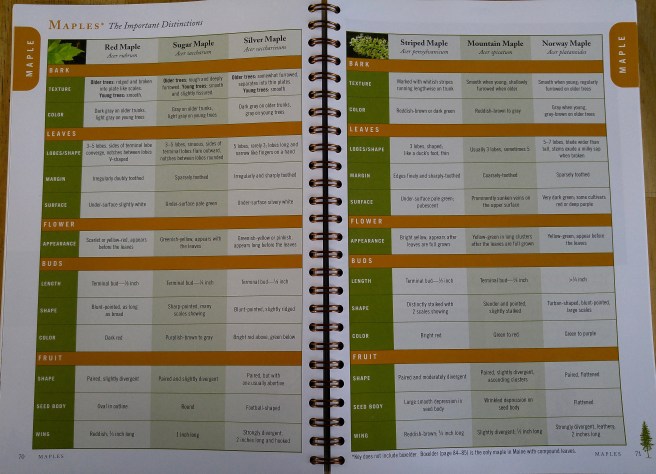

One of my favorite finds along this section was the bright red branches of young Striped Maples. From leaf and bundle scars to growth lines, lenticels and buds, their beauty was defined.

Another sight that surprised me–Striped Maple leaves still clinging, rather orangey in hue.

And here and there, as if in honor of the trail color, Red Pines reached skyward.

Eventually I reached the bottom, and turned right again, this time onto the stoplight trail–well, red and green at least.

My wildlife sitings were few and far between, but red squirrel tracks and a midden of discarded cone scales next to a dig indicated where the food had been stored in preparation for this day.

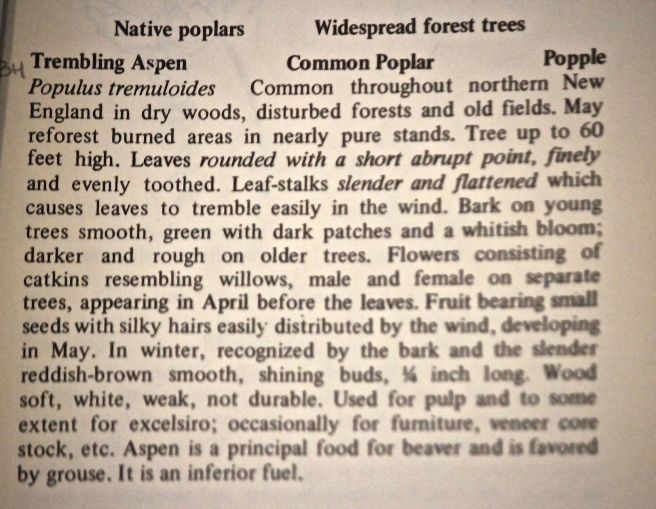

Following some grouse tracks took me off trail and tinder conks made their presence known.

The swirled appearance of these hoof fungi threw me off for a bit, but I think my conclusion is correct.

At last I reached the red trail that runs parallel with Heald Pond. Again, the fox tracks crossed frequently, but beside the path and leading to and fro the water and higher heights, another set of tracks confirmed my earlier suspicions.

Bobcat. I thought I smelled a pussy cat. I did.

Sometimes the bobcat moved beside the trail, while the fox crossed over. I’d thought when I started out this morning that I wouldn’t see too many tracks because the animals would have hunkered down for the storm. I was pleasantly surprised–for my own sake. For the sake of the animals, I knew it meant they were hungry and on a mission.

My own mission found me following the spur to Otter Rock. I noted that the fox had walked along the shoreline on its eternal hunt.

My hunt was of a different sort. No visit to the rock is complete without a look at the dragonfly exoskeletons. But today, it was a bit different because I, too, could walk on the ice. And so I found exoskeletons on parts of the rock I haven’t been able to view previously. Their otherworldly structure spoke to their “dragon” name.

The slit behind the head and on the back of one showed where the dragonfly had emerged from the nymph stage last spring. Or maybe a previous spring as some of these have been clinging to the rock for a long time.

While I was looking, I noticed some other pupae gathered together within a silky covering. Another reason to return–oh drats. I don’t know if I’ll be there at the right time, but with each visit, I’ll check in.

The sun was shining and warm. High 30˚s with slight breeze–felt like a summer day, with the sun reflecting off the snow. And at the mill, further reflection off the water. After four hours, it was time for me to check out.

As always, I was thankful for my visit, even though it wasn’t my original plan. Like the mammals, I’d been on a prowl–especially serving as the eyes for a friend who is currently homebound. I think she would have approved what I saw.