Community science, aka citizen science or participatory science, is an opportunity that allows laypeople like you and me to contribute meaningful data in a short amount of time that researchers can use to inform larger conservation efforts. And along the way, we get to learn more about a particular species, as well as those who share the same habitat.

For the past 25 years, I’ve had the pleasure of being involved in a variety of such local research projects, and one of my favorites is HERON Observation Network of Maine. For the last 16 years, friends and I have monitored first one and then several Great Blue Heron Rookeries (colonial nesting habitats).

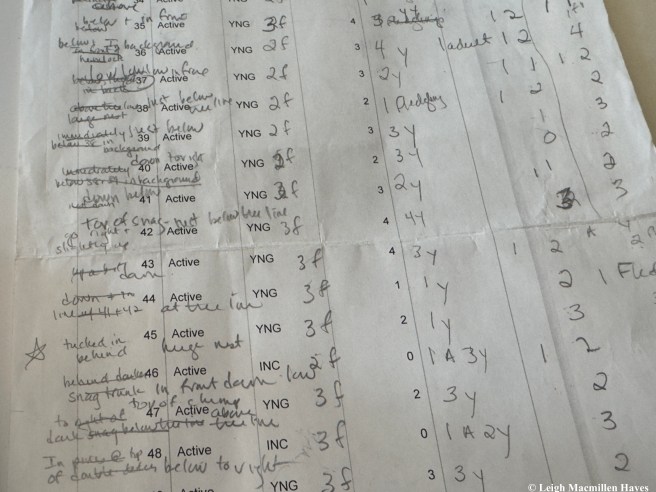

With landowner permission, we visit the rookeries several times between May and July and our job is to count the number of nests, number of active nests, inactive nest, adults, adults incubating, young, and fledglings. It’s rather intense work to move binoculars or cameras from tree to tree and some trees have double or triple-decker nests, and some nests are tucked into the background, and young can be difficult to see if they are so tiny that they are tucked down into the nest, and it’s easy to get confused and then have to start all over again.

Ah, but I can’t think of a better place to be on a summer morning than in these wetlands where aquatic life explodes in color and sound and texture and even life and death.

Sometimes it looks like a female is merely rearranging sticks to create a stronger nesting site.

But then . . . much to our surprise and delight, a fuzzy head is spotted and we know we have babes to look for, and suddenly that makes the job more difficult.

Especially when one head turns into two and we have to add another line to the tally sheet while the adult cools off and seemingly shades the youngsters.

The adults, meanwhile, not only take turns tending to their young, but they also take turns heading off to fish for meals. And when one is secured, that adult flies back to the nest and takes a few minutes to semi-digest the food.

At this point, the young begin to squawk, and I’ve often wondered if their sounds encourage the regurgitation that follows.

Ever so slowly, we can watch the food item come up the big bird’s throat and then with mouth open wide, it coughs and tada . . .

The young ones are happy to dine on their own form of baby food.

Even as they grow, the feeding ritual continues. One parent will fly in and join the family, while prepping the meal delivery.

And the other will fly out the back door in search of more to fill those ever-begging mouths.

And the kids will squawk until the remaining parent provides.

As weeks turn to a month or more, the birds turn into tweens, growing to the point where one wonders how they can all still fit in the nest, despite the fact that Momma built it to be about three feet wide, using sticks that Daddy provided.

And those tweens, like so many of their human counterparts, start to preen between meals, fixing their feathers over and over again.

Preening is important for several reasons: to keep feathers clean, free of parasites, waterproofed, and properly aligned for optimal performance because that first flight is getting closer and closer.

Despite all their preening, however, the younger birds are still dependent upon their parents for meals on wings because they haven’t yet fully fledged and started their own hunting habits.

In the midst of taking count, life happens all around us and we rejoice in any other sightings that might distract, even if it means starting the count again. That’s why, at one of the larger rookeries, we have a few landmark trees so we know if we get confused we can locate said tree and count from there.

We also try to keep track of where each nest is located in the landscape, but if you were to read my notes, you might get totally lost. I do!

Other distractions include Red-winged Blackbirds, even if their meal of choice is one of our beloved dragonflies.

Spiders also make meals of dragonflies, but despite the fact that this female Eastern Pondhawk Dragonfly got snagged, she was still a picture of beauty.

And usually when we spot Wood Ducks such as this male, they fly at the first inkling of our invasion into their space. But when you are far enough back and tucked into the trees beside the wetland, sometimes you are offered a glimpse, and this was one of many in an old snag.

In the hike to and fro the wetland, there other offerings, like a Snapping Turtle on her way up a hill to lay eggs.

And while pausing to talk, a Tree Frog was spotted.

And we gave great thanks that it allowed us to invade its inner circle for a few moments. Look as those toes, the ginormous suction cups that they are.

Even a Little Wood Satyr added magic to the scene.

And under a tree we spotted a number of pellets full of bones. We don’t know the creator of the pellet, nor the food that was consumed, but someone had a favorite feeding tree.

And now the rookeries are empty and the tweens have turned to teens and must hunt for themselves. It’s a task that takes great focus, but those eyes are all seeing.

And the beak is quick to snag.

And though the meal may be small, its one of many to come and success is key.

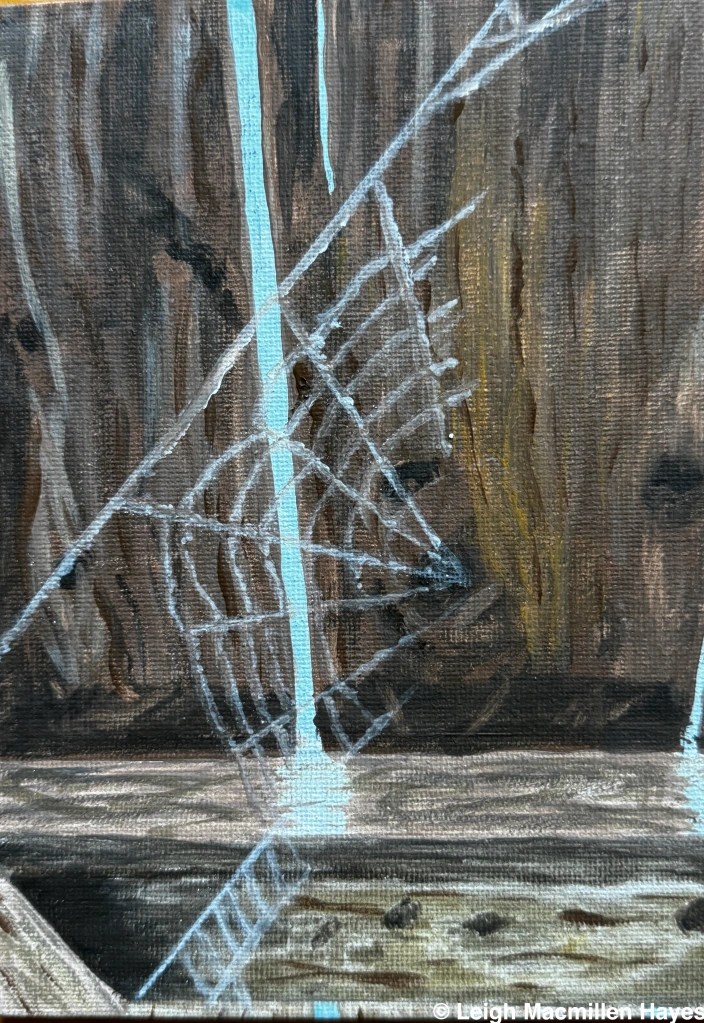

I’ve tried to commemorate these morning’s with a few paintings, including this teen and its catch.

And an adult on the hunt.

The Tree Frog.

And one of the rookeries, this one being the most successful.

2025 numbers:

Rookery 1: zero nests as has been the case for about six years now and I suspect I’ll be told not to bother with that one next year, but then again, some other Great Blue Herons could decide it’s just the right place and build a new rookery. The last year that we saw nests and birds, a Bald Eagle was in the area and within a week there were no more Herons to count.

Rookery 2: 21 nests observed; 18 inactive; 3 active; 5 adults; 3 young upon the first visit in May.

21 nests observed; 21 inactive. Yes, all nests were empty two weeks later. We knew when we didn’t hear any squawking as we approached that things were not good, but we were totally surprised to not spy any Herons. What had happened during the two week interval we’ll never know. But we suspect maybe a Bald Eagle in this locale as well. Or maybe an owl? Last year, the rookery had declined drastically from the first visit to the second, but not to this extent.

Rookery 3: 1 inactive nest; 59 active. YES! 60 nests in all, an increase of 7 from last year. And of 2024’s 53 nests, only 46 had been active. So 59 was a huge number! Have you ever tried to count birds in a wetland, where the nests are at least a football field or more away from you? It is not easy. And takes about two hours plus the hike in and out to complete. Oh, and the count: the number of adults varied with each visit, becoming less and less as the weeks went on because they were out hunting for larger fish to feed their growing brood. The youngsters at our last count: 122, plus 7 fledglings. That’s a lot of mouths to feed. And think of size of those birds, some nests with 4 kids, plus the two adults. Talk about tight living quarters.

Shoulder and neck muscles tense. The brain gets befuddled. Mosquitoes buzz in our ears.

But at the end of the morning, I can’t think of any place I’d rather be than spotting these two sharing a moment and give great thanks for all the moments we get to witness because we take part in monitoring the rookeries and making the Great Blue Herons count.

Thanks also to my companions. I won’t name them because I don’t want anyone to bug them about locations, just like I won’t name the actual locations or their State ID numbers because these are special places that need to be left undisturbed.