I dragged my guy along for a wander in the Hut Road neighborhood today and we made Willard Brook the center of our attention.

That being said, our journey began at Great Brook. I parked by the gate that isn’t open yet due to road conditions–not realizing that the only other vehicle belonged to a friend, who kindly left us a note we found under the windshield wiper as we drove away hours later.

The wind was wild and we felt it rattle our bones while we walked along Forest Service Road #4. That just meant a fast walk to the start of our adventure.

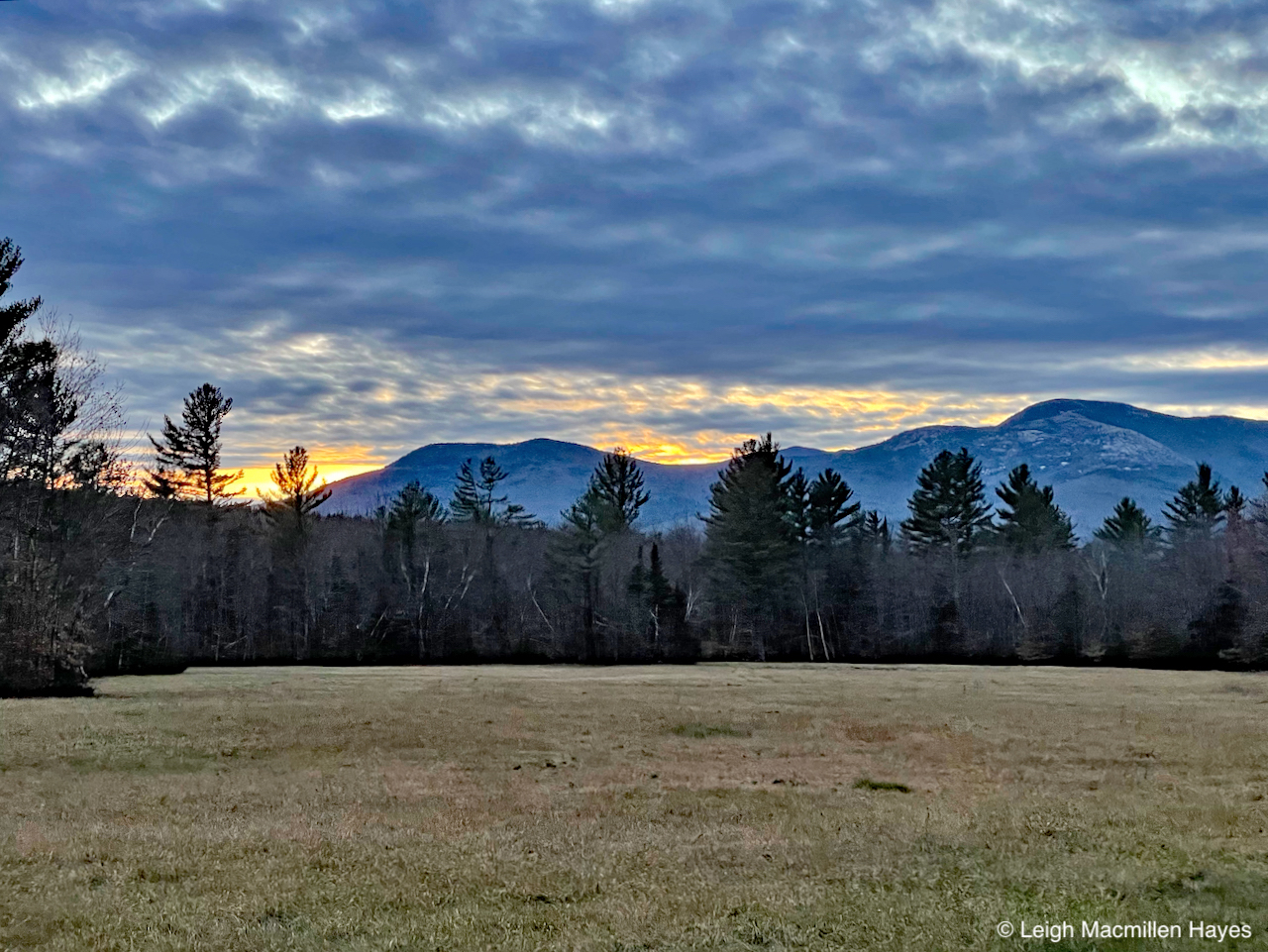

The beauty of this spot never ceases to take my breath away.

But we didn’t pause long because that wind was cold and icicles helped tell the story.

Lately, when I’ve tramped about in this area, I’ve been on the Great Brook Trail to start, but I contacted a few folks in the past two days because they’ve made comments on previous posts that indicated they have some understanding of the Native American presence that once existed here. And perhaps still does.

My friend, Jinny Mae, had intended to join us today, but that didn’t work as planned. She and I have explored this area a couple of times in the past few months and she’s my GPS techie, as well as a talented historian and naturalist. The above map is from a section of the 1858 map of Stoneham she posted. (Thanks JM for letting me borrow this without asking.)

As Jinny Mae indicates on her blog, this is from the 1880 map and there’s been a change in ownership of the neighborhood homes.

We chose a different route than the one she has outlined in red. Ours led to Willard Brook. Just before the snowmobile bridge, we turned right and began to follow the brook. I realized immediately that I’d been here before. Part of my quest was to take a look at stone placement and think about it not as Colonial only, but also as Pre-colonial or Native American. And so, I paused at every rock formation I found, including this circular configuration beside the brook. Current day fire pit? My guy didn’t think so. I don’t know.

As happens in our woods, we suddenly found ourselves visiting an old camp. Debris is scattered about. This particular piece from a stove front caught my guy’s attention. He was born in Taunton, Massachusetts, and immediately recognized this as coming from The Weir, an industrial section of town. If memory serves him right, there were at least three stove companies in that area.

My favorite will always be the mailbox, truly a tribute to snail mail.

Our intention had been to follow the brook north, but we let an already traveled trail lead us instead. Soon we came to another landmark I remembered, the great yellow birch. An old yellow birch. Very old. I led a bark workshop yesterday and this is one of the trees we talked about. Yellow birch can live to be 200 years old, much longer than any of their relatives. I don’t know the age of this monument, but I do wish I could hear the stories it has to tell of this land.

We turned left and followed the former road to Willard Brook. Colonial road or older?

I’ve learned from others to look at the shapes incorporated into stone walls and fences. I may be making this up because I’ve had an affinity with turtles since I was a young child and own quite a collection even to this day, but I see a turtle configured in this wall. Planned or coincidence? Worth a wonder.

Potentially another in this section of the same wall, but at the same time, this part seems more consistent in structure.

We ate the quickest lunch in our hiking history because our fingers were so cold. Even winter temps didn’t seem to bother us as much as today’s temp and wind chill. Lunch rock sat beside Willard Brook with Speckled Mountain above.

And then we backtracked up the road and I took my guy up to the Hut Road neighborhood. He’d not visited this particular community before, so was happy to make its acquaintance.

Our first encounter was with the Willard homestead of 1858; later known as the McKeen homestead of 1880.

As we moved up the hill to another foundation, we passed by this stonewall, where I wondered about the difference in stone size. A balancing act perhaps?

Homestead #2 belonged to the Durgins in 1858 and Rowlands in 1880. It’s one of my favorites because of the stone chamber within. Which came first–the stone chamber or the rest of the cellar? Was the entire cellar considered a root cellar?

Hence, a closer look. Oh yes, and the porcupine scat pile is still there in the back right-hand corner, but none of it is fresh. Darn.

On the outside of the chamber’s edge that connects with the cellar–again my imagination took over. Perhaps my turtle’s head is the large blocky rock bottom center. Or is it a smaller version in the rocks above. Am I seeing things that are not there? Overthinking as my guy would suggest?

Perhaps in the back wall?

And in the side? Again, I see a face peering out at me just up from the bottom center/left. Do you see it?

While I was busy photographing stone piles in the woods and wondering about their significance, my guy followed his nose and made a discovery that has eluded Jinny Mae and me for months.

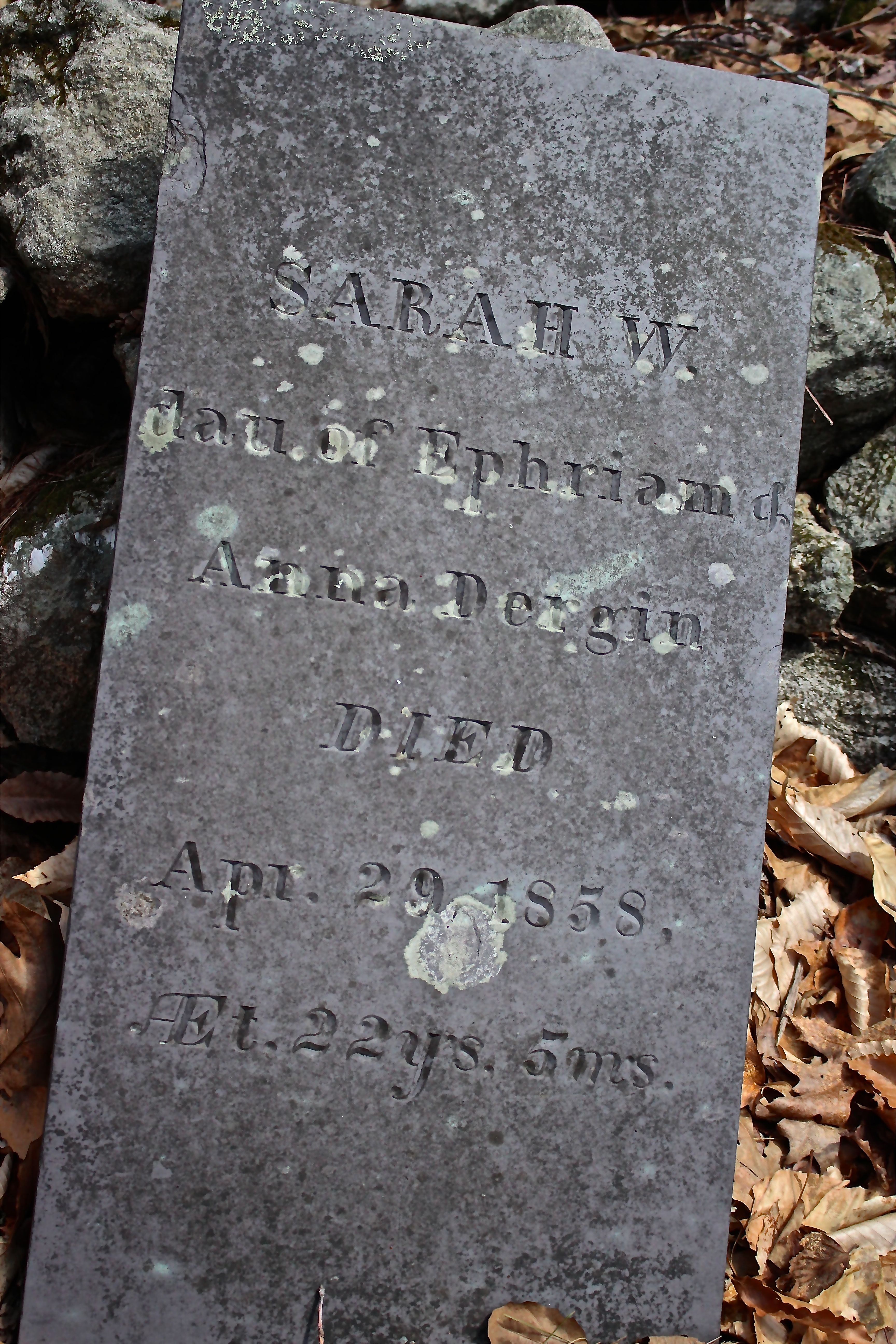

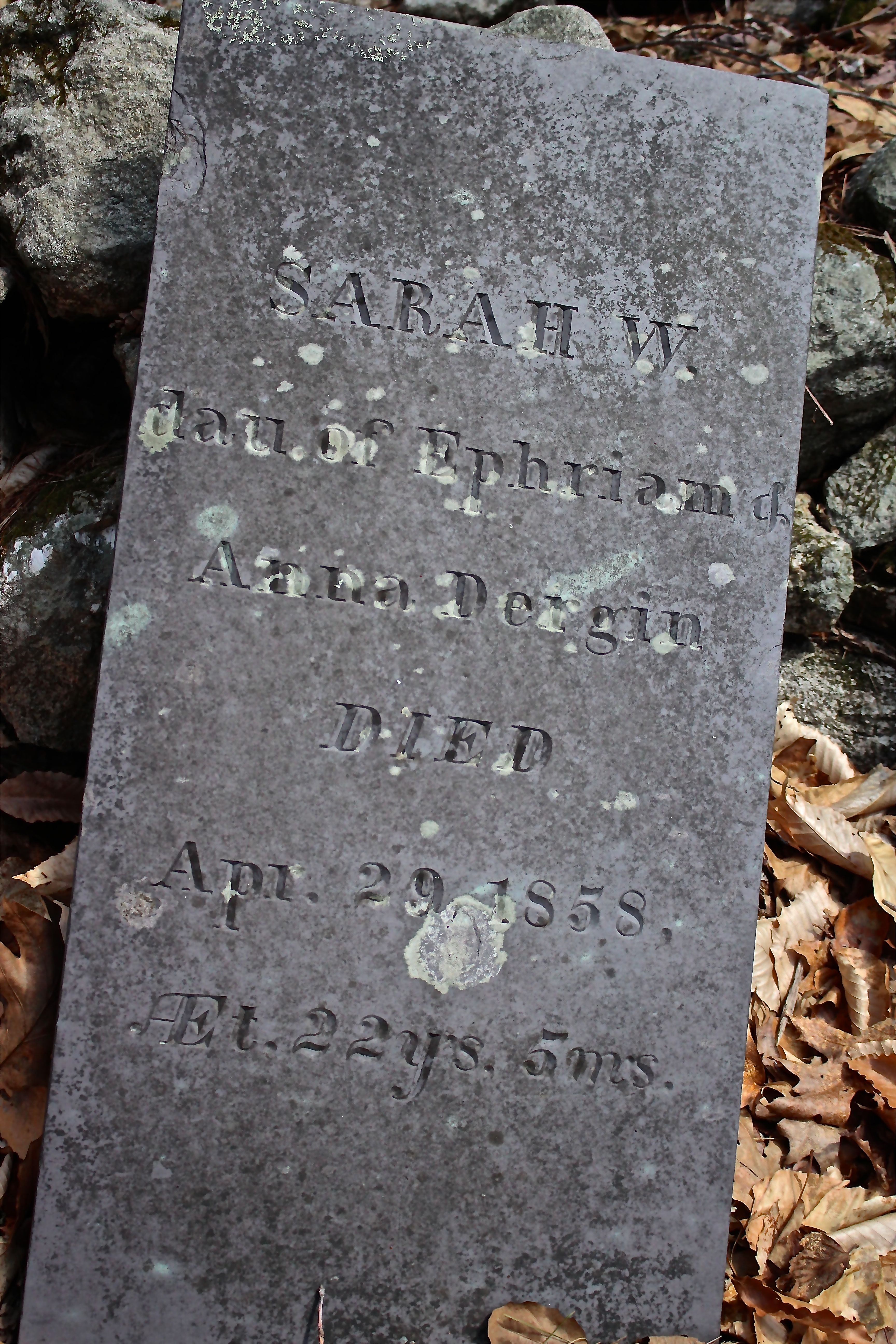

Just like that he found the cemetery.

Sarah, daughter of Anna and Ephraim, is the first tombstone. She died in 1858 at age 22.

Beside her, Mary, wife of Sumner Dergin, who died before Sarah–in 1856. She, too, was 22 years old. As best I can tell, Sarah and Sumner were siblings.

And Ephraim, Sarah’s father, who died in 1873 at age 81. Notice the difference in stone from the two girls to Ephraim? Slate to cement. And the name spelling–Dergin and Durgin. As genealogy hobbiests, we’ve become accustomed to variations in spelling.

I found the following on RootsWeb:

8. ANNA3 FURLONG (PATRICK2, JOHN1) was born 1791 in Limerick, Maine, and died 1873 in Stoneham, Maine. She married EPHRAIM DURGIN June 18, 1817 in Limerick, Maine14. He was born April 13, 1790 in Limerick, Maine, and died in Stoneham.

Children of ANNA FURLONG and EPHRAIM DURGIN are:

i.OLIVE4 DURGIN, b. 1811, Stoneham, Maine; m. DUNCAN M. ROSS, April 11, 1860, Portland, Maine.

ii.SALOMA DURGIN, b. 1813.

iii.ELIZABETH DURGIN, b. 1815.

iv.SALLY DURGIN, b. 1817.

v.SUMNER F. DURGIN, b. 1819, Of Stoneham, Massachusettes; m. MARY ANN DURGAN, July 11, 1853, York County, Maine; b. Of Parsonsfield, Maine.

vi.CASANDIA DURGIN, b. 1821.

vii.EPHRAIM DURGIN, b. 1823.

viii.FANNY DURGIN, b. 1825.

Sarah isn’t listed above. But . . . Sally and Sarah were often interchangeable.

Though only these three stones stand upright, leaning against a wall, this potentially was a large cemetery. And the view–Durgin Mountain.

Rather than backtrack again, we decided to travel cross-country back toward Willard Brook.

At the bottom of the hill, the area was filled with sphagnum moss and cinnamon and interrupted fern.

Though I didn’t find any bear trees today, I did find bear scat 😉

And plenty of moose sign.

The red maples offered numerous examples of the bull’s-eye fungi that I told yesterday’s workshop participants to notice. I encouraged them to develop bark eyes. Meanwhile, I’m working on my stone eyes. (not stoned!)

As we traipsed across the landscape, my guy recognized the large yellow birch we’d come upon earlier. And then we followed the walls down to Willard Brook where bushwhacking became the name of the game. Sometimes we found ourselves moving cautiously along the rocks in a dry section of riverbed–the overflow.

I kept my eyes open for stone treatments and found this twenty-foot rock slide that didn’t look natural. I have no idea what it represents.

One of the things I continue to notice and love about the woods around us–no matter how far from civilization you think you are, you never are. Notice the wooden wheel spokes.

I also noticed the trees and rocks across Willard, where the water’s rise and fall over the years has carved out a unique landscape and each entity is intertwined with the other.

Eventually we came out at the spot where we’d headed off the snowmobile trail and decided to turn right and follow it toward Evergreen Valley.

Though the walk was nice and the wind not so strong, we got to this modern-day cairn and felt we’d gone far enough. We turned back and bushwhacked down to Willard Brook.

Like Lewis, my guy scouted for a crossing. Like Clark, I followed.

Our spot to ford the brook looked easier than it was. He crossed first and landed without issue. Me too–um, almost. Only one foot slipped. His comment, “Good thing your hiking boots are waterproof.” My response, “Yeah, but my socks aren’t.” Oh well. I’ve had wet feet before and will again. When I finally took my boot off at home, I was surprised at how drenched the sock was.

We made our way through balsam fir saplings and hobblebush and a variety of other species and turned away from Willard assuming we’d eventually encounter Great Brook again. Success.

I’d been told to pay attention to Willard for Native American sites, and found this beside Great Brook. I have no idea what it represents.

And lo and behold as we headed back to our starting point, we found ourselves at a third foundation–a rather large one with a center chimney between two cellar holes and an addition behind it. It’s where the school probably stood in 1858 and A. Gray’s home in 1880.

Bricks still top the central chimney.

Just like that, we were back at our starting point–looking at it from the opposite side of the brook.

Thanks to all those I bugged about what to look for as we tramped about today. And thanks again to Jinny Mae for her talent. I can’t wait to share this trail with you again.

We’d wandered for hours and found plenty to wonder about–especially along Willard Brook.

You must be logged in to post a comment.