Though I grew up outside New Haven, Connecticut, and spent a great deal of time there as a child/tween/teen, I am not a city girl. In fact, stepping onto a sidewalk in even the smallest of cities yanks me from my comfort zone.

And so it was with great surprise that I met a city I rather liked. Over the last thirty years, I’ve passed through it numerous times, but twice this past week, I followed my tour guide from one monument to the next–my eyes wide and mouth gaping open with each new view, the obvious sign of a tourist.

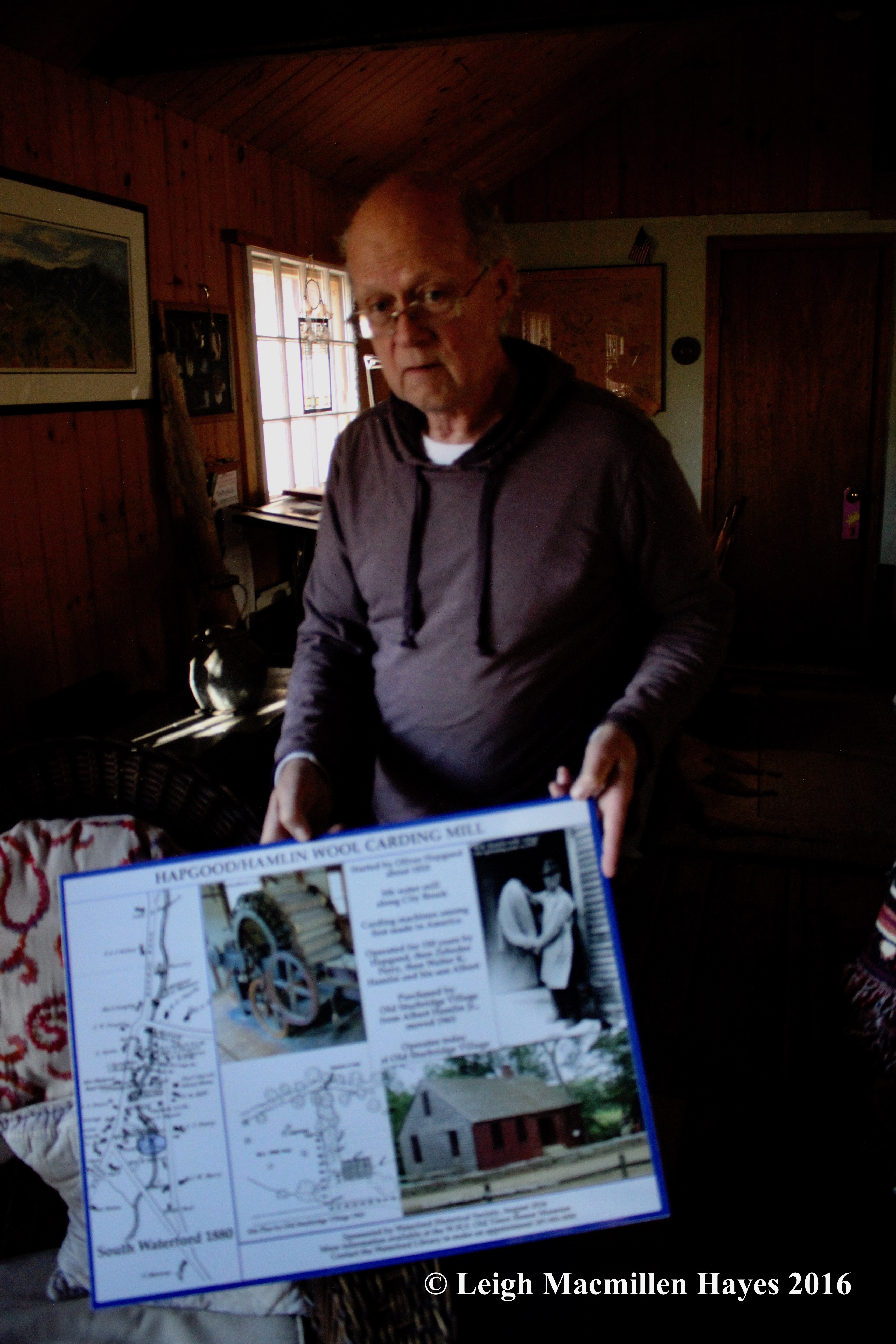

Meet my tour guide, Bob Spencer, who proudly displayed a future landmark sign.

Bob’s world view begins at City Center, aka Watson’s Falls.

From the home he and his wife, Gere, have made in a former mill, the view encompasses one of nine water privileges or mill sites. Theirs is the fifth privilege along the stream, which was originally granted to Isaac Smith in 1795 for a saw mill. Over the course of its lifetime, the building served as a cloth and linseed oil mill, saw mill, salt box factory and cider mill. I love that apples still dangle above the water, a reminder of that last rendition.

On Saturday, we stepped north for a few minutes, and chatted about the mill pond and its function while Bob pointed out foundations and retaining walls and told stories of the standing buildings.

Then we turned south along the brook, where remnants of dams and the stonework foundations of other water-powered mills flourished from the days of the town’s settlement until the mid 1900s.

Bob is a fellow writer and naturalist with a keen interest in history. I’m flattered that he shared this place with me as well as his own written musings:

For most travelers on busy state Route 35/37, our brook is of little interest or importance. To the village of South Waterford, however, a cluster of thirty buildings which lie on either bank of this stony rill, it has served as a source of life and vitality throughout much of history. Landforms here were carved into the granite bedrock as a much larger ice-age water course scoured out a valley between Bear and Hawk Mountains to the east and Mount Tir’em and Stanwood Mountain to the west. Native Americans gathered along its banks to fish and camp. Eighteenth century settlers were drawn to the environs for a source of their fresh water and of power to produce lumber and flour, which were essential to survival. Nineteenth century industrialists, before and after the Civil War, earned their livelihoods by producing both commercial and consumer goods traded locally and in cities such as Portland and Boston.

As we walk along he pointed out buildings still standing, those in stages of disrepair, and others that were merely memories. We paused by a meadow where he described the spring flooding events and I examined the evergreen wood ferns.

And then we noted the gouge that deepened as we climbed, where “a glacial moraine as melt water engorged the brook into a raging river 15,000 years ago. The brook serves as the marshy wetland home of fish, birds and mammals. Such a short stream can teach everyone who allows the time many lessons about our ecology systems: how they work and how they were born.”

At the emergence of the brook we’d followed with two smaller brooks (Mutiny and Scoggins), we paused as Bob described their origins and journeys.

And then we turned to Bear Pond–the outlet. The temperature was relatively warm and pond almost inviting.

With Bear Mountain overlooking, we’d reached the southern most point of the city.

On our return trip, we found numerous signs that local residents were still industrious. Sometimes they were successful and the trees fell to the ground.

As with all industrious efforts, there were times when hang ups prevented success.

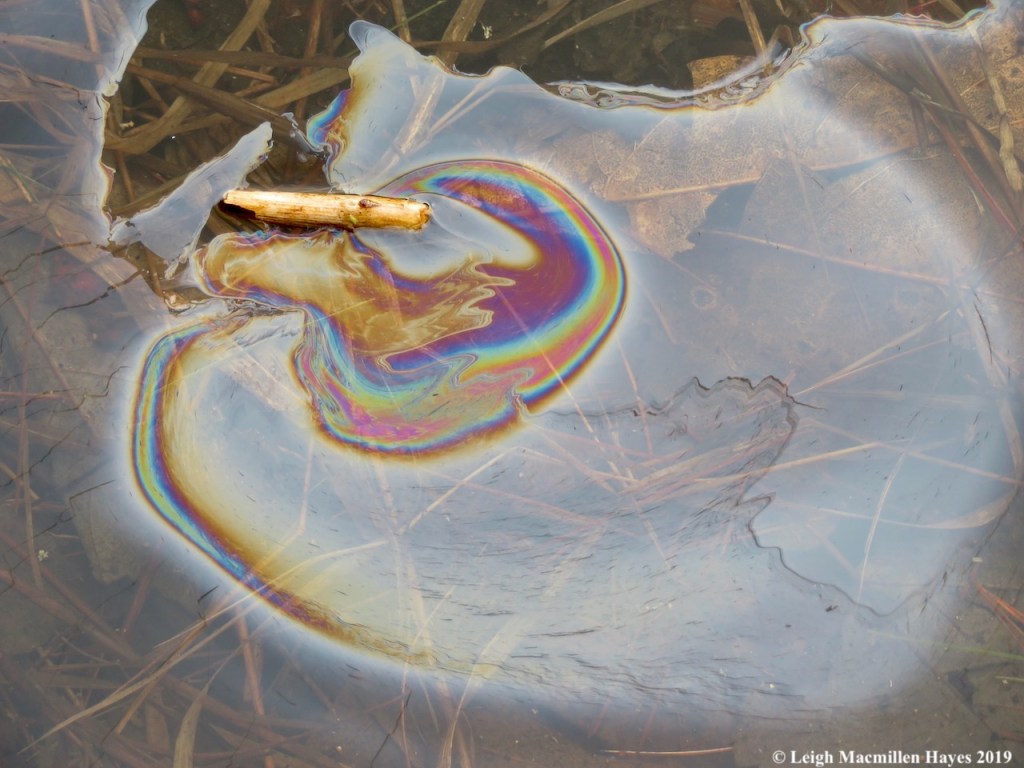

Sunshine and late afternoon reflections gave me a taste of why Bob referred frequently to the meditative nature of this place.

As we climbed a small hill and crossed a field, we again approached City Center.

And then we doubled back, walking to the intersection of Sweden Road with Routes 35/37. Plaster mills, bucket mills, a carding mill, saw mill and grist mill–waterpower was a necessity to any enterprise–beginning with lumber sawed for dwellings, grain ground for life-sustaining bread, shingles for siding and roofing, carded wool for the seamstress.

With the sun’s rays dipping lower in the sky, we stood in awe of the sluice and thought about the men and oxen and all the work that went into creating the mill–before the real work actually began.

How many times have I traveled past this site and never spied it? Too many.

After our first tour ended, I paused at the southernmost end of Bear Pond for further reflection.

But . . . there was still more to see of the city and so a few days later I eagerly joined my tour guide again. This time we walked north, and wondered about the rock placements and considered their role as runways that once helped direct the water flow.

All along, we saw evidence of human intervention.

We noted the feather and wedge marks on split stones.

Barbed wire made us think about the land being used for agriculture. Though it didn’t seem that the land had been plowed, we wondered if farm animals had roamed. Bob reminded me that a carding mill once stood nearby and so we envisioned sheep.

Barrel wire and staves made sense to us, but we didn’t always recognize the artifacts for their use.

We even found a cellar hole, or perhaps a cellar hole, that Bob hadn’t seen before. Of course, we speculated. It certainly had structure. But why was it cut out around large boulders, we wondered.

And we noted the industrial work of trees that forged their own way beside the brook.

For every sight that we seemed to understand, there were more that we didn’t. With his vast knowledge of local history and the land formations along the brook, Bob pointed out natural and man-made features, but even he admitted he didn’t always get it. The pile of obviously quarried granite was one such.

Suddenly, we reached what might be considered the crossroads of long ago and more recent past.

To the west, an obvious rock sluiceway.

To the right, stanchions from a former, yet more recent power site.

This was all located at the original spot of the first dam along the brook.

Curiously, Bob explained as we walked along, a more modern dam was built about a quarter mile north.

We’d reached Keoka Lake, formerly known as Thomas Pond. Supposedly, in the early 1900s, Thomas Chamberlain ran away from Native Americans and survived by hiding in a crack in a rock. Though the lake is no longer named for him, Tom Rock Beach holds his legacy. Today, the clouds told the story of the much cooler temperature.

Bob directed my attention to our left, where Waterford Flats was visible.

And then we looked south, to the outlet of Keoka and the beginning of City Brook–the place where it all began. Though no longer held by dams and funneled through the rock sluiceways, it was the water that passed this very way that once provided the energy converted by water wheels and turbines to power the life of the city.

“Waterford City” as it was known, has changed, though some standing monuments still speak to its former life. Until Saturday, I had no idea the brook was named City Brook or that South Waterford was known as a city, so named for the industry that once existed here.

As Bob wrote, “The age of industrial prosperity is now long gone, victim to growth of large manufacturing plants which required more powerful rivers and many other economic changes since the 1870s. At that time, South Waterford was dubbed “Waterford City” for the noise and bustle brought to the town by nine mills and many supporting outbuildings lining the brook. Invisible to today’s busy passerby are many remnants of a past industrial heyday: a large concrete and split stone ruin on the access road to Keoka’s modern dam, two-story stone work that served as the foundation for a 19th century bucket mill, a simple shingled mill building atop a 1797 stone dam beside the town’s last rustic stone bridge. Further exploration may reveal lost foundations beneath the water surface, a 36-inch rusty circular saw blade, burnt remains of Waterford Creamery or an earthen dam long overgrown by bushes and brambles. These vestigial remains of human endeavor are of historical interest to many.”

After our tour came to an end, I paused below the cider mill one more time–a fitting spot to share another of Bob’s ponderings on this place:

“The whirling bubble on the surface of a brook

admits us to the secret of the mechanics of the sky.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“It is appropriate to begin this study with a quote from American philosopher, existentialist Ralph Waldo Emerson (1802-1882), whose life spanned from early days of village settlement through the denouement of its industrial zenith. Emerson spent much of his boyhood visiting three aunts who lived in Waterford. He likely honed his naturalistic views while exploring City Brook or Mutiny Brook near Aunt Mary Moody Emerson’s home, Elm Vale, which was located across from the cemetery of the same name on Sweden Road.“

This is one city I’m thankful to have visited. And I look forward to further explorations.

I’m grateful to Bob for sharing this place with me and especially for pointing out all of his favorite meditative places. Meditation in the city–Waterford City style.