Being St. Nicholas Day, the day to honor the 4th century bishop from Myra who is the patron saint of children and sailors, I was reminded of a time when we were heading home and our youngest asked, “Mom, are you Santa?”

I love this story and so even if you’ve read it before, I hope you’ll enjoy it again.

He’d held onto the belief for far longer than any of his classmates. And for that reason, I too, couldn’t let go. And so that day as we drove along I reminded him that though the shopping mall Santas were not real, we’d had several encounters that made believers out of all of us.

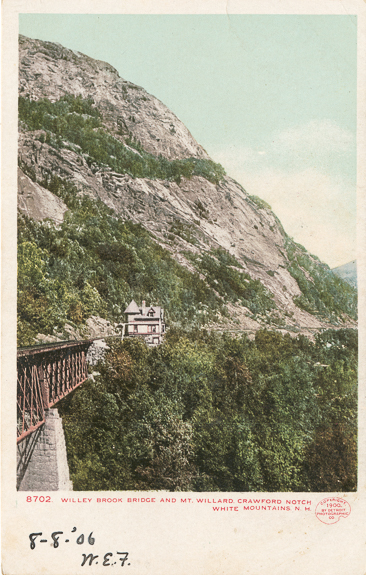

The first occurred over thirty years ago when I taught English at a school in New Hampshire. Across the hall from my classroom was a special education class. And fourteen-year-old Mikey, a student in that class, LOVED Santa.

Each year the bread deliveryman dressed in the famous red costume when he made his final delivery before Christmas break. To Mikey’s delight, he always stopped by his classroom. That particular year, a raging snowstorm developed. The bread man called the cafeteria to say that he would not be able to make the delivery. School was going to be dismissed after lunch, but we were all disappointed for Mikey’s sake.

And then . . . as the lunch period drew to a close, Santa walked through the door and directly toward Mikey, who hooted with joy as he embraced the jolly old elf. As swiftly as he entered, Santa left. I have no doubt that that was Santa.

And about twenty-seven years ago, as the boys sat at the kitchen counter eating breakfast on Christmas Eve morning, we spotted a man walking on the power lines across the field from our house. We all wondered who it was, but quickly dismissed the thought as he disappeared from our view, until . . . a few minutes later he reappeared.

The second time, he stopped and looked in our direction. I grabbed the binoculars we kept on the counter for wildlife viewings. The man was short and plump. He wore a bright red jacket, had white hair and a short, white beard. The boys each took a turn with the binoculars. The man stood and stared in our direction for a couple of minutes, and then he continued walking in the direction from which he’d originally come. We never saw him again. I have no doubt that that was Santa.

Another incident occurred about seventeen years ago, when on Christmas Eve, our phone rang. The unrecognizable elderly male voice asked for our oldest son. When I inquired who was calling, he replied, “Santa.”

He spoke briefly with both boys and mentioned things that they had done during the year. I chatted with him again before saying goodbye. We were all wide-eyed with amazement. I have no doubt that that was Santa.

Once I reminded our youngest of those stories, he dropped the subject for the time being. I knew he’d ask again and I also knew that none of us wanted to give up the magic of anticipation for those special moments we know as Christmas morning, when the world is suddenly transformed.

I also knew it was time he heard another story–that of Saint Nicholas, the Secret Giver of Gifts. It goes something like this . . .

The nobleman looked to Heaven and cried, “Alas. Yesterday I was rich. Overnight I have lost my fortune. Now my three daughters cannot be married for I have no dowry to give. Nor can I support them.”

For during the Fourth Century, custom required the father of the bride to provide the groom with a dowry of money, land or any valuable possession. With no dowry to offer, the nobleman broke off his daughters’ engagements.

“Do not worry, Father. We will find a way,” comforted his oldest daughter.

Then it happened. The next day, the eldest daughter discovered a bag of gold on the windowsill. She peered outside to see who had left the bag, but the street was vacant.

Looking toward Heaven, her father gave thanks. The gold served as her dowry and the eldest daughter married.

A day later, another bag of gold mysteriously appeared on the sill. The second daughter married.

Several days later, the father stepped around the corner of his house and spied a neighbor standing by an open window. In shocked silence, he watched the other man toss a familiar bag into the house. It landed in a stocking that the third daughter had hung by the chimney to dry.

The neighbor turned from the window and jumped when he saw the father.

“Thank you. I cannot thank you enough. I had no idea that the gold was from you,” said the father.

“Please, let this be our secret,” begged the neighbor. “Do not tell anyone where the bags came from.”

The generous neighbor was said to be Bishop Nicholas, a young churchman of Myra in the Asia Minor, or what we call Turkey. Surrounded by wealth in his youth, Bishop Nicholas had matured into a faithful servant of God. He had dedicated his life to helping the poor and spreading Christianity. News of his good deeds circulated in spite of his attempt to be secretive. People named the bishop, “The Secret Giver of Gifts.”

Following Bishop Nicholas’ death, he was made a saint because of his holiness, generosity and acts of kindness. Over the centuries, stockings were hung by chimneys on the Eve of December 6, the date he is known to have died, in hopes that they would be filled by “The Secret Giver of Gifts.”

According to legend, Saint Nicholas traveled between Heaven and Earth in a wagon pulled by a white steed on the Eve of December 6. On their doorsteps, children placed gifts of hay and carrots for the steed. Saint Nicholas, in return, left candy and cookies for all the good boys and girls.

In Holland, Saint Nicholas, called Sinterklaas by the Dutch, was so popular for his actions, that the people adopted him as their patron saint or spiritual guardian.

Years later, in 1613, Dutch people sailed to the New World where they settled New Amsterdam, or today’s New York City. They brought the celebration of their beloved patron with them to America.

To the ears of English colonists living in America, Sinterklaas must have sounded like Santa Claus. Over time, he delivered more than the traditional cookies and candy for stockings. All presents placed under a tree were believed to be brought by him.

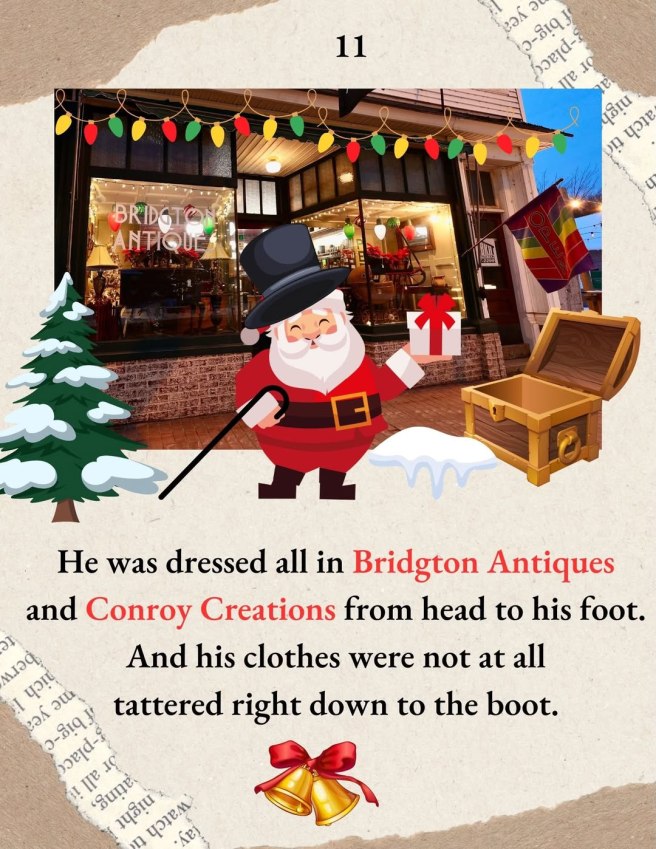

Santa Claus’ busy schedule required he travel the world in a short amount of time. Consequently, as recorded in Clement Moore’s poem, “The Night Before Christmas,” a sleigh and eight tiny reindeer replaced the wagon and steed.

Since Saint Nicholas was known for his devout Christianity, the celebration of his death was eventually combined with the anniversary of Christ’s birth. December 24th or Christmas Eve, began to represent the Saint’s visit to Earth.

Traditionally, gifts are exchanged to honor the Christ Child as the three Wise Men had honored Him in Bethlehem with Frankincense, Gold and Myrrh.

One thing, however, has not changed. The gifts delivered by Saint Nicholas or Santa Claus, or whomever your tradition dictates, have always and will continue to symbolize the love people bear for one another.

Though they are now adults, my continued hope for my sons is that they will realize the magic of Christmas comes from the heart and that we all have a wee bit of Santa in us. Yes, P, Santa is real.

May you and everyone continue to embrace the mystery and discover wonder wherever you look. And may you find joy in being the Secret Giver of Gifts.