We parked on the little dirt connector road between Route 160 and Lord Hill Road, close to Bog Road, because we knew the conditions would be such that driving into Brownfield Bog would be impossible. Besides, walking would offer more time to catch up on each other’s lives. Well, I’m afraid I did most of the talking, but at least my friend Bridie is up to speed on my life. Hers is so full of students and research and writing, that just having time to breathe in the fresh air of her childhood backyard was enough.

At the old shed, we paused to admire the work of her mom, Kathy McGreavy, a potter who created this tile map of Brownfield Bog in 2017 as her capstone project for the Maine Master Naturalist program. And we wondered how many of the same species we might see or encounter today.

One particular tile always elicits a shared memory, for I was with Bridie when we spotted an Eastern Ribbon Snake slither across the road and down into the water.

It was then that I learned that Ribbon Snakes are a species of special concern in Maine, and rather uncommon. Since then, I’ve seen at least one more in the bog and a few more in several other local spots, but each sighting is special, and always I return in my mind to that first time.

And why the wire across the tile art work? It seems woodpeckers like to peck at the tiles and Kathy had to repair a few a year or two ago.

We couldn’t go out on the bog today, as we had done previous winters. After all, we are on the cusp of spring, and didn’t trust the ice. But from the edge we admired Pleasant Mountain forming the backdrop–and always giving us an idea of where home is located.

Down a side road, which we were able to walk being not flooded (yet), we found our way to Pirate’s Cove along the Saco River and the water is high and mighty and muddy. For a few minutes we watched in silence. Well, we were silent, but the river wasn’t.

Returning to the main drag, we made our way back to the Old Course of the river and were greeted by the most delightful bird chorus, including the conk-le-rees of the Red-winged Blackbirds.

With their bright red shoulder patches bordered below in yellow, they were calling from high perches among the shrubs.

Puffing out while calling is indeed a breeding activity, and so the race is on. May the best males find a mate.

Our other bird sightings included this White-breasted Nuthatch, plus Hairy Woodpeckers, American Tree Sparrows, Canada Geese, and a thousand Wood Ducks. Or so it seemed. The fact that they moved every time we spotted them, even if two hundred yards away, might mean that there weren’t quite that many, but rather that we kept meeting the same ones in different locations.

We also saw signs of Pileated Woodpecker works. Not only do they excavate holes while in search of Carpenter Ants, they also shred and chisel and in these woods, that seems to be a favorite activity. We wondered why, but couldn’t come up with an answer.

We did, however, do what Bridie taught me to do a million years ago and searched for scat. Bingo! Though we saved this thought for another day, we did wonder if we dissected the scat, would we be able to tell about how many ants had been consumed?

And no adventure with Bridie would be complete without some tracking in the mix. Our snowpack is quickly dwindling and where three days ago at home, we still had a foot, now there are lots of bare spots and what snow is left might be only about four inches.

That said, we relished the finds we did make, including lots of Vole tunnels like these. And I reminded Bridie that she was the one who introduced me to the subnivean layer, that microhabitat between the ground and the bottom of the snowpack (think back to Thanksgiving 2024), which provides insulation and protection for many animals, like the Voles, who happen to be on everyone’s dinner menu.

Our other finds included Raccoon tracks,

Mink,

and Coyote,

plus a family of Coyotes on some sand at Goose Pasture.

And, of course, our adventure could not be complete without discovering several Coyote scats.

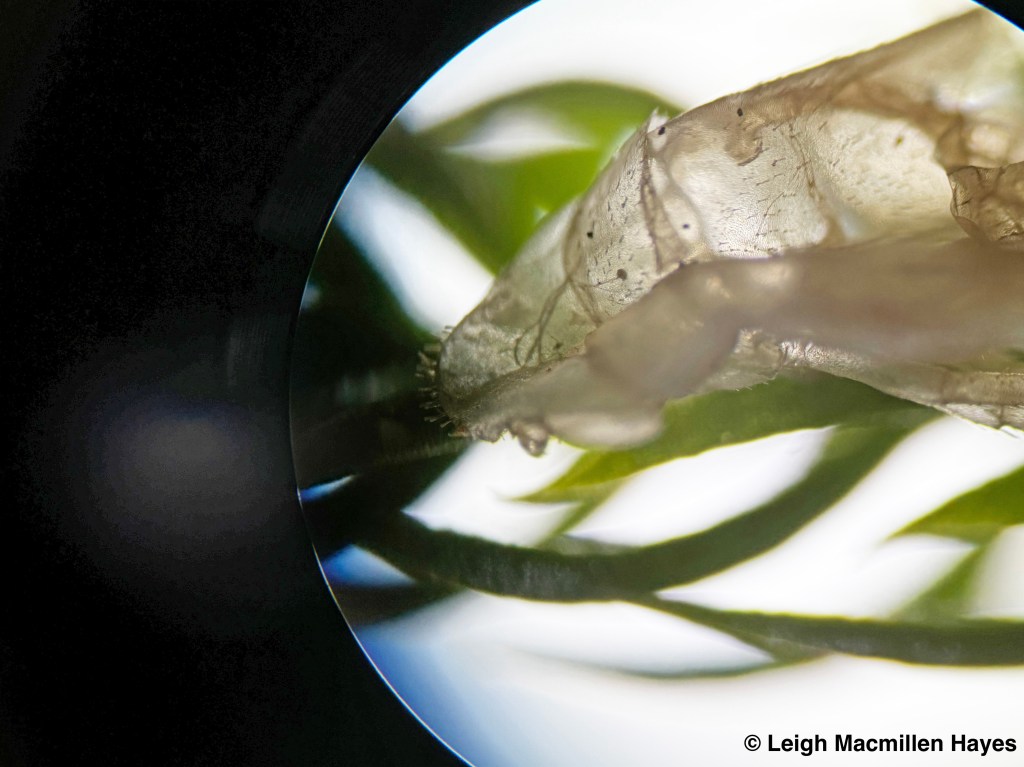

And just for good measure, we met one large Six-spotted Fishing Spider.

Okay, so it wasn’t really as big as the close-up made it look.

There were also beaver works in various places, though we suspected this was a wee bit old, but not older than a few months ago based on the color of the wood. The warmer temps made the sap flow a bit.

There are a bunch of well-mudded lodges in the bog, but we didn’t see any hoped for activity today.

We did, however, discover some scent mounds and know that claiming territory is an important assignment that will become more significant as the ice begins to melt and the two-year-olds leave the lodge to venture off on their own and claim a territory.

Next, we turned our focus to a few shrubs, including the Winterberry. While I still have some dried bright red berries as decorations in my house, most of the berries on branches have shriveled and we wondered why the birds hadn’t dined on them when they were ripe.

What we discovered, much to our delight, was that some had been procured by little brown things, presumably mice, and had been consumed in a bird’s nest. It’s illegal to take bird nests without a permit and this is one reason, they are recycled into homes for other critters.

What totally surprised us about the Winterberry, however, was that we found one shrub with the berries still bright red and plump, as if today was December 18th and not March 18th. Again, we wondered why.

We also found a few of last season’s cranberries hiding under their leaves. That reminded me of another day I’d spent searching for cranberries in the bog years ago–and though I told Bridie about it, I’ll save that two-day story for another day.

Leatherleaf also had offerings to provide, in the form of little flower buds along the woody stems.

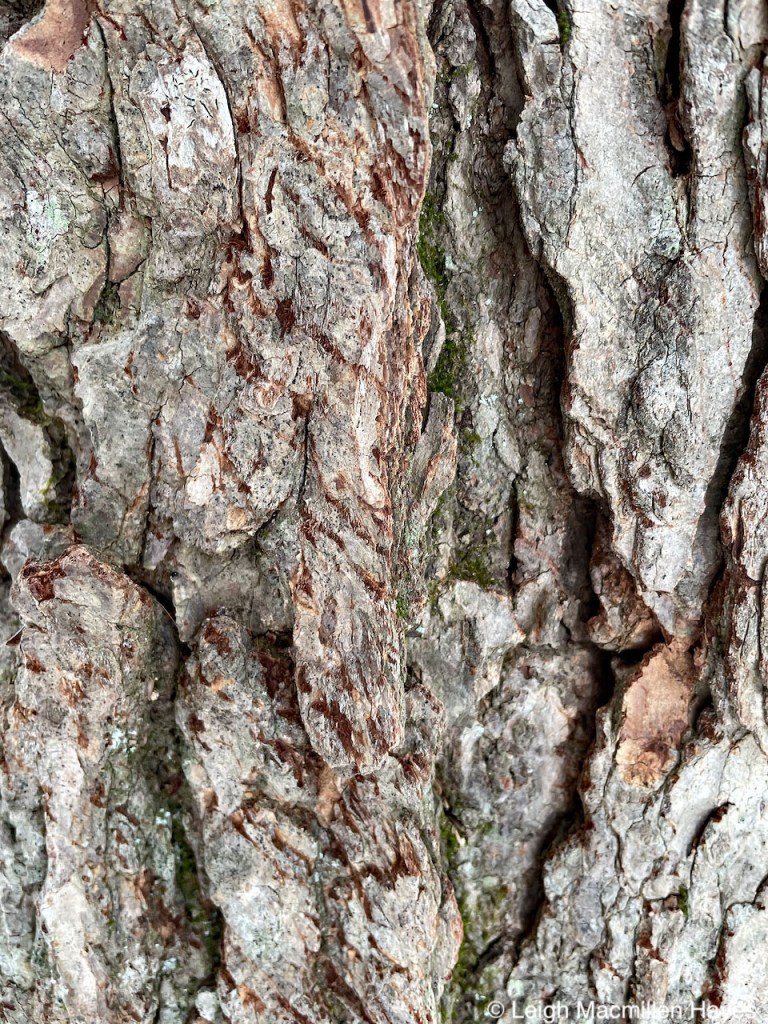

At last we reached the old Oak at Goose Pasture and stood there for a bit taking in the sun and warmth and feeling like it was a bit of a beach day. But, our time together was coming to a close, and we knew this would be our turn-around point.

That said, there were a couple of other gifts to share together, as today was the first day this year that the two of us saw Pussy Willows in bloom.

And, drum roll please, we heard them before we spotted them way over on the other side of the bog, but their distinctive call told us to look that way and sure enough there were two Sandhill Cranes.

Like the Wood Ducks they flew, but the two morphed into three as we watched them take to the air.

We’d been blessed. In so many ways.

And at the end of our time together, after traveling 6.2 miles, we needed to say our goodbyes.

The thing is, she wasn’t really with me, which I realized when I went to put my arm around her for our selfie shot. But, in my mind, she was and I had the best time Bogging with Bridie today, her birthday.

Happy Birthday, Bridie McGreavy!