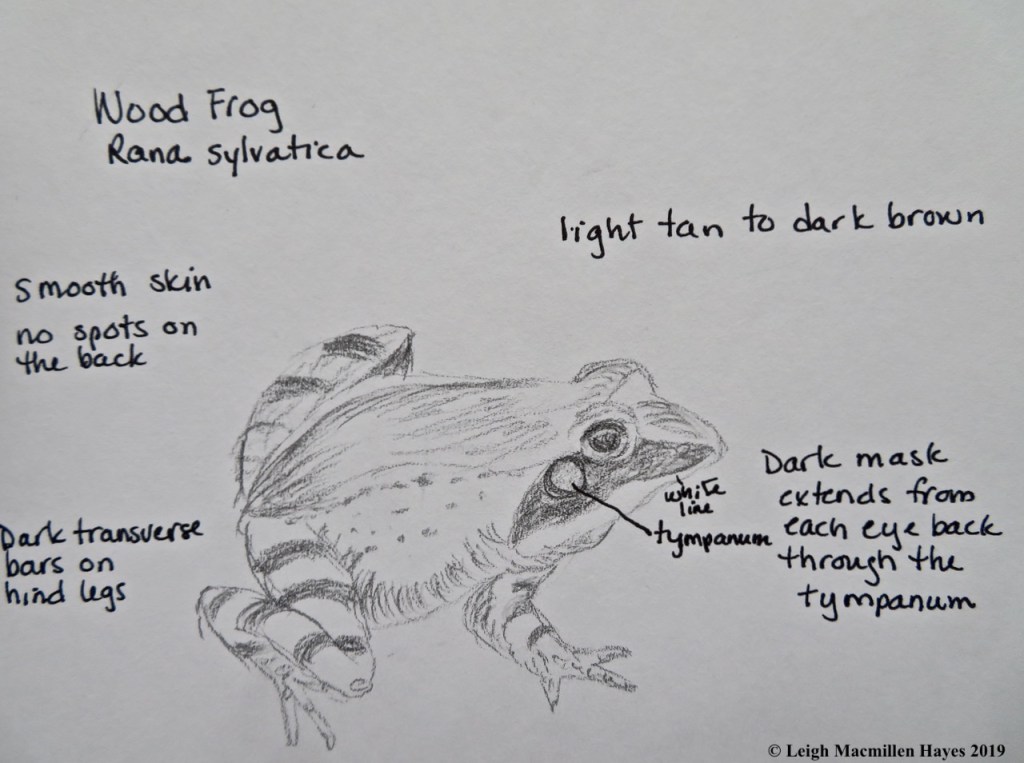

There’s no music quite like the Wood Frog’s defiant chorus, sung when the ice is barely off the vernal pool and the ground still covered with patches of snow. Singing together, they sound like dozens of quaking ducks. Wood Frogs are often the first Maine frogs to break winter’s quiet, beating Spring Peepers by a few days or even a week.

Their vocal prowess extends to silence. Once we approach a vernal pool and they sense danger (perhaps through vibrations), they cut off their song altogether, as though timed by some unseen conductor. The purpose of all this calling is finding a mate, of course. Male Wood Frogs, once they’ve called in some unwitting females, can be tenacious in the extreme–even if their suitor happens to be the wrong species.

This morning, as Greater Lovell Land Trust Docent Linda Wurm and I approached a pool on the Heald and Bradley Ponds Reserve, the symphony was eerily still.

And so we began to circle around, our eyes scanning the watery surface for clumps of eggs. Our hope was to either see a male hug a female in an iron-lock grasp, forming the mating embrace called amplexus, or evidence of their date.

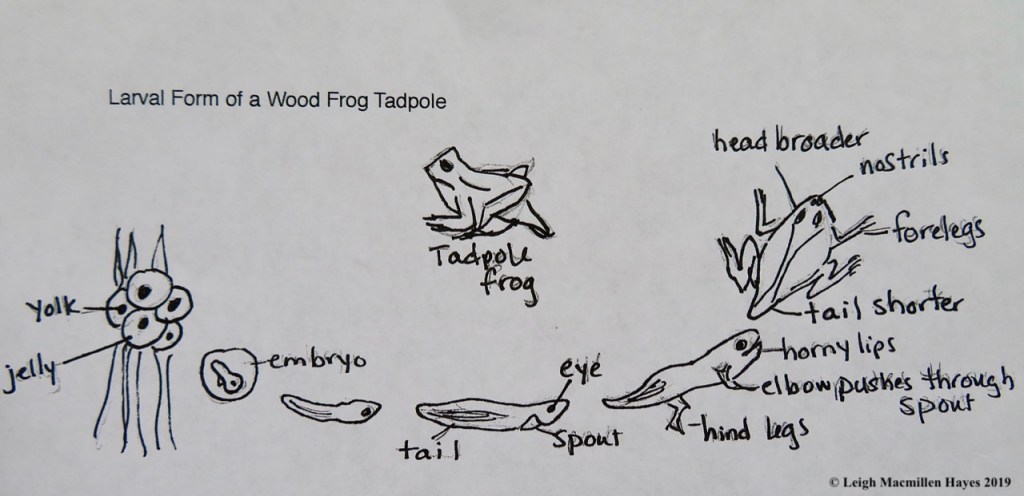

And we were rewarded. At least one female had laid eggs fertilized by a male. As is their habit, the female attached the mass to a twig and the tiny black embryo of each egg was surrounded by a perfectly round, clear envelope about one-third inch in diameter. These gelatinous blobs can consist of up to 1,500 individual eggs. Egg-mazing indeed.

The embryos will hatch into small brownish-black tadpoles in a week or two, or longer given how chilly the water was today. As they grow, their rounded tail fins will become translucent–almost mottled with gold and blackish flecks.

Wood Frog tadpoles grow at varying rates depending on water temperature, tadpole density, and available food resources, but tend to develop within about two months to become adults. Unfortunately for them, but in the web of life good for others, tadpoles often succumb to cannibalism, especially to their larger relatives. They are also eaten by predacious diving beetles, salamanders, turtles, and birds.

We only found one, maybe two egg masses, but this pool isn’t known for many. What it is known for is its Fairy Shrimp population and I’m sorry to report that we found not a one. But, we did spy a few handsome hemlock varnish shelf fungi.

And by them some red squirrel middens that made us happy for we saw few of these all winter.

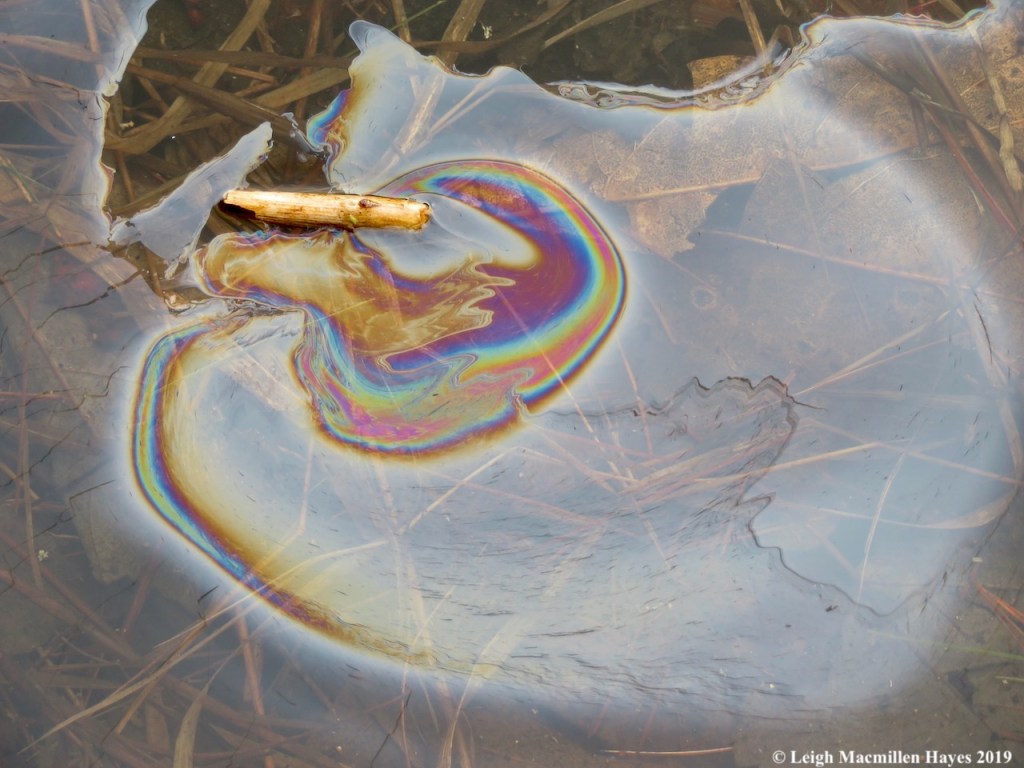

Right behind the fungi and midden, something else in the water caught our attention and Linda focused with a keen eye.

My photo wasn’t the clearest, but upon some leaves and twigs we spotted spermatophores left behind by male Spotted Salamanders. They remind me of cauliflower, their structures consisting of pedestals topped with sperm. Though we couldn’t see any milky masses of salamander eggs, we hope that on future visits we will.

Spotting a Spotted Salamander is a rare treat. With their bright yellow spots on a sleek, shiny black back, they are even more nocturnal and elusive than the Wood Frogs. They are actually mole salamanders and spend most of their time burrowed underground.

As we circled back around the pool, a White-breasted Nuthatch mimicked our searching eyes and probed under some bark, its long narrow beak seeking beetles.

Every few seconds it took a break and surveyed the world that included us.

We, too, surveyed the world, and suddenly at our feet we discovered eggs we’d not seen previously. What were they doing about a foot out of the water?

And to whom did they belong? At first I considered Pickerel Frog, but on closer examination I thought they might be Wood Frog.

And then Linda shifted one clump a wee bit with a stick and we found what may have been the entrails. Life happens in vernal pools and this one was no different. Had a predator stopped by? Perhaps a raccoon or skunk or chipmunk or raccoon? But, why didn’t it eat the eggs? Again, so many questions.

With the field microscope, we looked at the eggs again and were almost one hundred percent certain that they were Wood Frog.* We did place some of them back in the water, but wondered if they were viable.

For all the eggs that are laid, it’s hard to believe that only 10% will survive. But the truth is that most die before transforming into adults and leaving their pools. The reasons are varied: the ponds dry up; or they are hunted down by predators: or they die of diseases.

After a few hours, we pull ourselves away, grateful for the time to explore this wild place–full of life . . . and death.

*I’ve reached out to Dr. Rick Van de Poll about the eggs out of water–if, by chance, he responds, I’ll update this post so stay tuned.

And now from Rick:

Hi Leigh!

Fascinating find! Having just seen a few predated egg masses today I can definitively say they are spotted salamander eggs. The blackish coloration is likely imparted by the stomach acids of a raccoon, who apparently gorged and threw them back up, along with a few frog parts. Again, while its not too common to see this kind of things around vernal pools, it does make for for a pretty good ‘who-dunnit’!

Rick