My sister knows me well. And so this summer she gifted me a copy of Kathryn Aalto’s The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh: A walk through the forest that inspired the Hundred Acre Wood.

My relationship with Pooh began as a child, though I can’t remember if my sister or mother read the stories to me or if I first meet him on my own. It doesn’t matter. What’s more important is that I had the opportunity to meet him and to stay in touch ever since.

Our relationship continued when I took a children’s literature course as a high school senior and after reading and writing about the books, I sketched characters from several stories including A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh to complete an assignment. My framed collage still decorates a wall in my studio. And later, I met Pooh again through The Tao of Pooh here I listened more closely to his lessons about life. When I needed to interpret a song for a sign language class, it was to Pooh I turned: Kenny Loggin’s “House at Pooh Corner.” And Pooh was a dear friend when our sons were young and the oldest formed his own relationship with the residents of the Hundred Acre Wood.

And so it was with great joy that I opened Aalto’s book and immediately related to her dedication: “To the walkers of the world who know the beauty is in the journey.”

When a friend noted that Winnie-the-Pooh is 90 years old today, I knew that this had to be the Book of November. Alan Alexander Milne published When We Were Young and A Gallery of Children in the two years prior to 1926 and followed with The House at Pooh Corner in 1928. All are as meaningful today as they were then–perhaps more so.

Aalto is an American landscape designer, historian and writer who lives in Exeter, England. I know it’s not good to covet someone else’s life, and yet . . . I do.

Her book begins with biographical background about Milne and how he came to be at Ashdown Forest and the Five Hundred Acre Wood. I think one of my favorite facts that she shares is that while at boarding school, his mother sent care packages that included bunches of flowers grown in her garden. Upon receiving them, he was pulled home by the sight and scent. Perhaps secretly, my sons would appreciate that, but they’d never let on.

States Aalto: “We value the books for simple expressions of empathy, friendship, and kindness. The stories are classics as they express enduring values and open our hearts and minds to help us live well. But as I read about Milne and walked around England with my children, I saw how they also tell another story: the degree to which the nature of childhood has changed in the ninety years since Milne wrote the stories. There is less freedom to let children roam and explore their natural and urban environments. There are more digital distractions for our children that keep them indoors and immobile, and heightened parental fears that do so as well.”

With that, I am reminded of a childhood well spent exploring the environs of our Connecticut neighborhood and beyond and not returning home until we heard Mom shout our names from the back door. (Or a certain next door neighbor told me that my mother was calling.)

While C.R.’s explorations with his stuffed animals became the muses for his father’s stories, the landscape also provided inspiration.

That landscape still exists, though time has had a way with it. Aalto takes us there through her photographs and words. She begins with a visit to the farm, village of Hartfield, and the forest located steps to the south. Referring to the Ashford Forest, she comments: “It is still a place of solitude where people can walk half a day without meeting another person. There are no overt signs pronouncing your arrival in Pooh Country. There are no bright lights or billboards, no £1 carnival rides, no inflatable Eeyores, Owls, or Roos rising and falling in dramatic flair. There are no signs marking the dirt lane where Milne lived, nor pub grub with names like “Milne Mash and Peas” or a “Tigger’s Extract of Malt Cocktail” on ice. A quiet authenticity–historical, literary, and environmental–has settled over the landscape.” Ah, yes. A place to simply be and breathe and take it all in.

A photograph of C.R.’s secret hideaway in a tree reminds us that the stories are about real people and real places and based on real life events, all with a dash of real imagination. Aalto examines every aspect of this.

A week ago today, while exploring a similar woodland in New Hampshire with a dear friend, I convinced her to step inside a tree cavity, much the way the real Christopher Robin used to do a Cotchford Farm. At heart, we can all be kids again.

I love that Aalto provides us with a closer look at the flora and fauna of the forest. From flowers and ferns to birds, butterflies, moths, damselflies and dragonflies, and red tail deer, she gives us a taste of C.R. and Pooh’s world.

And she reminds us to get out and play, including rules for Poohsticks. I think it is more important than ever that all members of our nation step outside, find a Pooh bridge, drop a stick and run to the other side. As Aalto says in rule #9: “Repeat over and over and over and . . . ”

I also like that she mentions one special visitor to Ashdown Forest, who spent many hours examining carnivorous sundews.

I’m rather excited by that because just yesterday I discovered sundews, though rather dried up, growing on our six-acre woodland. We’ve lived in this house for 24 year and I’ve never spotted these before. The land is forever sharing something “new” with me and I’m happy to receive each lesson.

I’m also thankful for a feisty faerie with whom I share this outdoor space. Sometimes her statements are dramatic and I can only imagine the cause of her recent frustration.

It’s not too late to revisit your inner Pooh. To take the journey. And while you are there, I highly encourage you to get to know him and his place through The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh by Kathryn Aalto.

P.S. Thanks Lynn ;-)

The Natural World of Winnie-the-Pooh, first edition, by Kathryn Aalto, © 2015

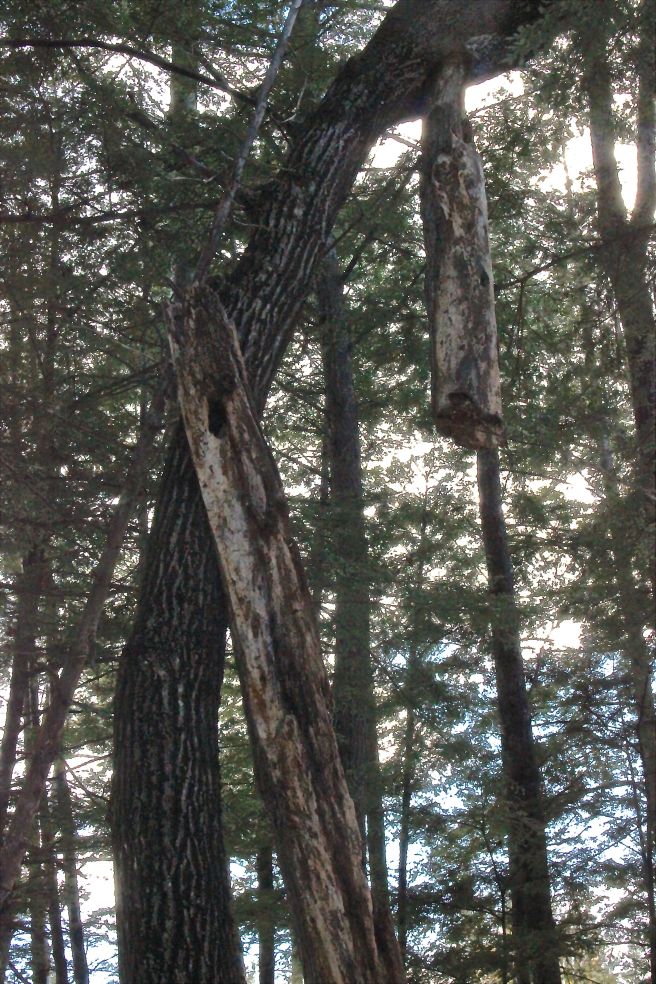

Check out this tree that I pass by each time I step into our woodlot. My guy and I were commenting on it just the other day–he tried pushing, but it stood firm. This morning, fresh wood chips indicated that the pileated woodpecker had paid a visit in the last 24 hours.

Check out this tree that I pass by each time I step into our woodlot. My guy and I were commenting on it just the other day–he tried pushing, but it stood firm. This morning, fresh wood chips indicated that the pileated woodpecker had paid a visit in the last 24 hours. It’s a well-visited tree. What will the woodpeckers do when it finally does fall? Two things. First, they’ll continue to visit it because apparently it’s worthy of such. And second, they’ll find other trees; there are several others just like this.

It’s a well-visited tree. What will the woodpeckers do when it finally does fall? Two things. First, they’ll continue to visit it because apparently it’s worthy of such. And second, they’ll find other trees; there are several others just like this. I was feeling a bit grumpy when I headed out the door, but finding the recent woodpecker works and emerging from the cowpath onto the power line where I was captured by the whitegreenbluegray of the world as I looked toward Mount Washington put a smile on my face. My intention was to walk along the barely used snowmobile trail as far as I could. I wasn’t sure if open water would keep me from reaching the road, which is a couple of miles away, but decided to give it a try.

I was feeling a bit grumpy when I headed out the door, but finding the recent woodpecker works and emerging from the cowpath onto the power line where I was captured by the whitegreenbluegray of the world as I looked toward Mount Washington put a smile on my face. My intention was to walk along the barely used snowmobile trail as far as I could. I wasn’t sure if open water would keep me from reaching the road, which is a couple of miles away, but decided to give it a try. Just because that was my plan doesn’t mean that’s what happened. Maybe that’s what I love best about life–learning to live in the moment. This moment revealed the spot where deer sunk into the snow just off the snowmobile trail and a bobcat floated on top.

Just because that was my plan doesn’t mean that’s what happened. Maybe that’s what I love best about life–learning to live in the moment. This moment revealed the spot where deer sunk into the snow just off the snowmobile trail and a bobcat floated on top. I turned 180˚ and found more tracks on the other side of the snowmobile trail. And so began today’s journey into the woods. I was feeling proud of myself for backtracking the animal–following where it had come from rather than where it had gone so I wouldn’t cause unnecessary stress. Yet again, I stress out all the mammals because of my constant movement–and so many I don’t see because they hear me coming. Anyway, I followed the bobcat for quite a while, noticing that it continued to follow the deer and even crossed over a couple of vole tunnels that already have their spring appearance. It’s much too warm much too soon.

I turned 180˚ and found more tracks on the other side of the snowmobile trail. And so began today’s journey into the woods. I was feeling proud of myself for backtracking the animal–following where it had come from rather than where it had gone so I wouldn’t cause unnecessary stress. Yet again, I stress out all the mammals because of my constant movement–and so many I don’t see because they hear me coming. Anyway, I followed the bobcat for quite a while, noticing that it continued to follow the deer and even crossed over a couple of vole tunnels that already have their spring appearance. It’s much too warm much too soon. What I discovered is that this mammal was checking out stumps and along the way circled around them. And then it seemed that there might be two because suddenly I was following rather than backtracking. So much for that plan. What I do like is how this photo shows the mammal’s hind foot stepping into the same space the front foot had already packed down–direct registration, just a little off center.

What I discovered is that this mammal was checking out stumps and along the way circled around them. And then it seemed that there might be two because suddenly I was following rather than backtracking. So much for that plan. What I do like is how this photo shows the mammal’s hind foot stepping into the same space the front foot had already packed down–direct registration, just a little off center. Its prints are in the bottom right-hand corner, but then it appeared to walk across the top of this nurse-log. After that, I had to circle around looking for the next set of prints.

Its prints are in the bottom right-hand corner, but then it appeared to walk across the top of this nurse-log. After that, I had to circle around looking for the next set of prints. Under some of the hemlocks, there was little to no snow. Eventually I lost the bobcat’s trail, which is just as well.

Under some of the hemlocks, there was little to no snow. Eventually I lost the bobcat’s trail, which is just as well. I didn’t realize until I looked up that I was still in familiar territory.

I didn’t realize until I looked up that I was still in familiar territory. I first spotted this widow maker 20+ years ago. It never ceases to amaze me.

I first spotted this widow maker 20+ years ago. It never ceases to amaze me. I decided that rather than return to the snowmobile trail, I’d continue deeper into the woods. I had an idea of where I’d eventually end up, but if you’ve traveled these woods with me recently (Marita and Dick can vouch for this), you’ll know that the logging operation has thrown me off and not all of my landmarks are still standing. It’s that or they just got up and moved. Anyway, I was lost for about an hour, but continued moving slowly through sometimes deep snow (relatively speaking this winter) and other times puddly conditions. It was a slog to say the least. My friend, Jinny Mae, had warned me about water hidden beneath the snow and I found it. More than once.

I decided that rather than return to the snowmobile trail, I’d continue deeper into the woods. I had an idea of where I’d eventually end up, but if you’ve traveled these woods with me recently (Marita and Dick can vouch for this), you’ll know that the logging operation has thrown me off and not all of my landmarks are still standing. It’s that or they just got up and moved. Anyway, I was lost for about an hour, but continued moving slowly through sometimes deep snow (relatively speaking this winter) and other times puddly conditions. It was a slog to say the least. My friend, Jinny Mae, had warned me about water hidden beneath the snow and I found it. More than once. I also found other cool stuff. British lichen bearing bright red caps.

I also found other cool stuff. British lichen bearing bright red caps. A hemlock wound that indicated the last time this land was logged. I counted to 25. That makes sense.

A hemlock wound that indicated the last time this land was logged. I counted to 25. That makes sense. A hemlock cone and seeds on a high spot of snow–not the usual stump, log or branch, but still a high spot. Apparently the red squirrel that had gone to all the work of taking the cone apart to eat the seeds had been scared away. Perhaps it will return, or another, or I’ll be admiring hemlock saplings in a few years.

A hemlock cone and seeds on a high spot of snow–not the usual stump, log or branch, but still a high spot. Apparently the red squirrel that had gone to all the work of taking the cone apart to eat the seeds had been scared away. Perhaps it will return, or another, or I’ll be admiring hemlock saplings in a few years. Porcupine scat below another hemlock.

Porcupine scat below another hemlock. And a few snipped off twigs–porcupine style.

And a few snipped off twigs–porcupine style. A mystery perhaps. I love a mystery. So, scattered on the snow–bits of hemlock bark.

A mystery perhaps. I love a mystery. So, scattered on the snow–bits of hemlock bark. And an apparent path up the tree. But . . . look up. This tree is dead. I don’t think this is porky work.

And an apparent path up the tree. But . . . look up. This tree is dead. I don’t think this is porky work. Could it be that where the bark is missing a woodpecker has been at work?

Could it be that where the bark is missing a woodpecker has been at work? I found fresh browse on striped maple–that had been previously browsed based on the scars.

I found fresh browse on striped maple–that had been previously browsed based on the scars. And red maple that had received the same treatment.

And red maple that had received the same treatment. Witch hazel was not to be overlooked. I think this is the longest deer tag I’ve encountered–to date.

Witch hazel was not to be overlooked. I think this is the longest deer tag I’ve encountered–to date. You may not appreciate this, but I couldn’t resist. So . . . to whom does it belong? Either a coyote or bobcat. It’s filled with hair and I’m leaning toward the latter. Of course, I want it to be the latter.

You may not appreciate this, but I couldn’t resist. So . . . to whom does it belong? Either a coyote or bobcat. It’s filled with hair and I’m leaning toward the latter. Of course, I want it to be the latter. I, um, brought some home in a doggy bag. Not all of it, mind you, because it is a road sign to others. I’m not sure how they do it, but members of the same family can apparently identify gender, health and availability by such works. And members of other families may read this as a territory marker. There was a copious amount, so it could be that the same or two animals used this spot. Just sayin’.

I, um, brought some home in a doggy bag. Not all of it, mind you, because it is a road sign to others. I’m not sure how they do it, but members of the same family can apparently identify gender, health and availability by such works. And members of other families may read this as a territory marker. There was a copious amount, so it could be that the same or two animals used this spot. Just sayin’.

It’s right beside a deer run. In the past two years, the deer visited this spot, but I’ve noticed much more activity this winter. The stone wall is hardly an obstacle. And the junipers–prickly as they are to me, the deer seem to enjoy them.

It’s right beside a deer run. In the past two years, the deer visited this spot, but I’ve noticed much more activity this winter. The stone wall is hardly an obstacle. And the junipers–prickly as they are to me, the deer seem to enjoy them. One thing I did notice that I don’t understand. The sheep laurel that grows here has recently been browsed.

One thing I did notice that I don’t understand. The sheep laurel that grows here has recently been browsed. Deer tracks below it and the nature of the work lead me to believe that the ungulates fed on it. Hmmm . . . I thought that sheep laurel was poisonous to wildlife. But then again, deer are browsers, not staying in one spot long enough to consume a large amount so perhaps it doesn’t affect them if they eat a bit here and there. If you know otherwise, please enlighten me.

Deer tracks below it and the nature of the work lead me to believe that the ungulates fed on it. Hmmm . . . I thought that sheep laurel was poisonous to wildlife. But then again, deer are browsers, not staying in one spot long enough to consume a large amount so perhaps it doesn’t affect them if they eat a bit here and there. If you know otherwise, please enlighten me. Another thing–yes, if you look closely at leaves, you’ll find them. These hot chili peppers don’t appear just on the surface of snow. They are snow fleas, aka springtails. With their spring-loaded tails they can catapult themselves an inch or so. We never look for them once the snow melts, but they are still abundant on organic debris. They’re easiest to locate on leaf litter, but also can be seen on soil, lichens, under bark, decaying plant matter, rotting wood and other areas of high moisture as they feed on fungi, pollen, algae or decaying organic matter.

Another thing–yes, if you look closely at leaves, you’ll find them. These hot chili peppers don’t appear just on the surface of snow. They are snow fleas, aka springtails. With their spring-loaded tails they can catapult themselves an inch or so. We never look for them once the snow melts, but they are still abundant on organic debris. They’re easiest to locate on leaf litter, but also can be seen on soil, lichens, under bark, decaying plant matter, rotting wood and other areas of high moisture as they feed on fungi, pollen, algae or decaying organic matter. Though it was warm under the sun, my fingers were getting cold as I sketched, so I packed up to head home. Back in our woodlot, I decided to follow a deer trail rather than my own. And to them I give thanks. Beside a hemlock tree, pinesap’s woody capsules called out. I’d found some at the start of winter–along the cowpath. And now a second patch. It really does pay to go off my own beaten path.

Though it was warm under the sun, my fingers were getting cold as I sketched, so I packed up to head home. Back in our woodlot, I decided to follow a deer trail rather than my own. And to them I give thanks. Beside a hemlock tree, pinesap’s woody capsules called out. I’d found some at the start of winter–along the cowpath. And now a second patch. It really does pay to go off my own beaten path. While pinesap has several flowers on one stalk, a few feet later and I came upon Indian pipe, which has one flower (now a woody capsule) atop its stalk. Notice how hairy the pinesap is compared to the Indian pipe.

While pinesap has several flowers on one stalk, a few feet later and I came upon Indian pipe, which has one flower (now a woody capsule) atop its stalk. Notice how hairy the pinesap is compared to the Indian pipe. I’m afraid this photo is a bit fuzzy, but I’m still going to use it because it’s too dark to head out and take another. These cup lichens serve as my pixie goblets to all of you who have stuck with me for this journey–both today’s and the past year. Thank you so much. The year flew by and I’m a better person for this experience. Well, I think I am. What has made this past year so special is the paying attention. The slowing. The recognizing. The questioning. I’ve learned a lot and I trust you’ve learned a wee bit as well. Who knows where the path will lead me next, but I sure hope you are along to wander and wonder.

I’m afraid this photo is a bit fuzzy, but I’m still going to use it because it’s too dark to head out and take another. These cup lichens serve as my pixie goblets to all of you who have stuck with me for this journey–both today’s and the past year. Thank you so much. The year flew by and I’m a better person for this experience. Well, I think I am. What has made this past year so special is the paying attention. The slowing. The recognizing. The questioning. I’ve learned a lot and I trust you’ve learned a wee bit as well. Who knows where the path will lead me next, but I sure hope you are along to wander and wonder.