Following this morning’s Greater Lovell Land Trust trek at Chip Stockford Reserve, where we helped old and new friends form bark eyes as they examined various members of the birch family, my feet were itchy. Not in the scratchy sort of way–but rather to keep moving.

It was a lovely day for a hike and Sabattus Mountain in Lovell was my destination. I love this little mountain because it offers several different natural communities and great views.

Though there are a few softwoods on the lower portion of the trail, it’s really the land of a hardwood mix.

About halfway up, the neighborhood switches to a hemlock-pine-oak community. It was then that I began looking for downed hemlock twigs in an array at the base of trees. I’ve found them here before, and today I wasn’t disappointed.

The twigs had been chewed off and dropped by a porcupine as evidenced by the 45˚-angled cut and incisor marks. Though red squirrels also nip off the tips of hemlock twigs, they do just that–nip the tips. Porcupines cut branches.

Downed branches usually mean scat, but I searched high and low and under numerous trees that showed signs of activity and found none. A disappointment certainly.

My search, however, led me to other delightful finds that are showing up now that most of the snow has melted, like this pipsissewa that glowed in the afternoon sun. As is its habit, the shiny evergreen leaves look brand new–even though they’ve spent the winter plastered under snow and ice. A cheery reminder that spring isn’t far off.

At the summit, I got my bearings–the ridge of Pleasant Mountain and Shawnee Peak Ski Area to the southeast.

To the southwest, the asymmetrical Roche Moutonnée, Mount Tom, visible as it stands guard over Kezar Pond in Fryeburg.

And to the west, Kezar Lake backed by Mount Kearsarge in New Hampshire. I wanted to venture further out on the ledge, but some others hikers had arrived and I opted not to disturb their peace.

Instead, I sat for a few minutes and enjoyed the strong breeze offering possibilities as it floated over the summit and me.

Crossing the ridge, I left the trail and found more porcupine trees, including this young hemlock that had several cuts–look in the upper right-hand corner and lower left hand. A number of younger trees along this stretch will forever be Lorax trees.

On the outcrop of quartz, I paused to admire the golden moonglow lichen–it’s almost as if someone drew each hand-like section in black and then filled in the color, creating an effect that radiates outward.

I was pleasantly surprised to find a patch of polypody ferns on what appears to be the forest floor but was actually the rocky ridge. Notice how open-faced it is, indicating that the temperature was quite a bit warmer than what I’d seen on cold winter days.

Sunlight made the pinna translucent and the pompoms of sori on the backside shone through.

The trail doesn’t pass this glacial erratic, but I stepped over the logs indicating I should turn left and continued a wee bit further until I reached this special spot.

Its backside has been a porcupine den forever and ever. Nice to know that some things never change.

After returning to the trail, I followed it down through the hemlocks and oaks. This is my favorite part of the trail and though it’s a loop, I like to save this section for the downward hike–maybe because it forces me to slow down.

For one thing, it features the land of the fairies. I always feel their presence when here. Blame it on my father who knew of their existence.

I had a feeling a few friends were home–those who found their way into a fairy tale I wrote years ago. I left them be–trusting they were resting until this evening.

As swiftly as the community changed on the upward trail, the same was true on my descent.

On our morning trek, we’d looked at paper birch, but none of the trees we saw showed the range of colors like this one–a watercolor painting of a sunset.

This one shows the black scar that occurs when people peel bark. The tree will live, but think about having your winter coat torn off of you on a frigid winter day. Or worse.

Off the trail again, I paused by a few trees that I believe are black birch. Lately, a few of us have been questioning black birch/pin cherry because they have similar bark. The telltale sign should be catkins dangling from the birch branches. I looked up and didn’t see catkins, but the trees may not be old enough to be viable. This particular one, however, featured birch polypores. So maybe I was right. I do know one thing–it’s not healthy.

And then I reached a section of trail that I’ve watched grow and change in a way that’s more noticeable than most. I counted the whorls on these white pines and determined that they are about 25 years old. I remember when our sons, who are in their early twenties, towered over the trees in their sapling form. Now two to three times taller than our young men, the trees crowded growing conditions have naturally culled them.

Nature isn’t the only one that has culled the trees. Following their selection to be logged, however, some became planters for other species.

Nearing the end of the trail another view warmed my heart. Three trees, three species, three amigos. Despite their differences, they’ve found a way to live together. It strikes me as a message to our nation.

Perhaps our leaders need to turn the spotlight on places like Sabattus. It’s worth a wonder.

From the parking lot, I decided to begin via the blue trail by the kiosk. It doesn’t appear on the trail map, but feels much longer than the green trail–possibly my imagination. Immediately, I was greeted at the door of the shop by sweet fern, aka Comptonia peregrina (remember, it’s actually a shrub with foliage that appear fern-like). The striking color and artistic flow of the winter leaves, plus the hairy texture of the catkins meant I had to stop and touch and admire.

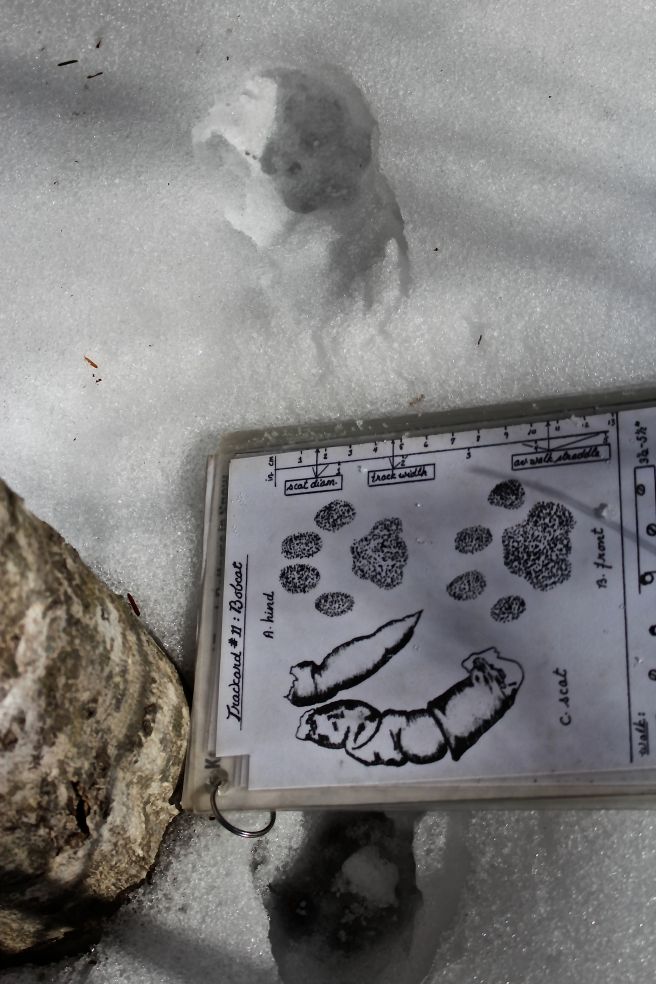

From the parking lot, I decided to begin via the blue trail by the kiosk. It doesn’t appear on the trail map, but feels much longer than the green trail–possibly my imagination. Immediately, I was greeted at the door of the shop by sweet fern, aka Comptonia peregrina (remember, it’s actually a shrub with foliage that appear fern-like). The striking color and artistic flow of the winter leaves, plus the hairy texture of the catkins meant I had to stop and touch and admire. And only steps along the trail another great find–bobcat tracks. This china shop immediately appealed to moi.

And only steps along the trail another great find–bobcat tracks. This china shop immediately appealed to moi. My

My  When I got to a ledgy spot, I decided to explore further–thinking perhaps Mr. Bob might have spent some time here. Not so–in the last two days anyway.

When I got to a ledgy spot, I decided to explore further–thinking perhaps Mr. Bob might have spent some time here. Not so–in the last two days anyway. The best find in this spot–red squirrel prints. A few things to notice–the smaller feet that appear at the bottom of the print are the front feet–often off-kilter. Squirrels are bounders and so as the front feet touch down and lift off the back feet follow and land before the front feet in a parallel presentation. In a way, the entire print looks like two exclamation points.

The best find in this spot–red squirrel prints. A few things to notice–the smaller feet that appear at the bottom of the print are the front feet–often off-kilter. Squirrels are bounders and so as the front feet touch down and lift off the back feet follow and land before the front feet in a parallel presentation. In a way, the entire print looks like two exclamation points. As I plodded along, my eyes were ever scanning and . . . I was treated to a surprise. Yes, a beech tree. Yes, it has been infected by the beech scale insect. And yes, a black bear has also paid a visit.

As I plodded along, my eyes were ever scanning and . . . I was treated to a surprise. Yes, a beech tree. Yes, it has been infected by the beech scale insect. And yes, a black bear has also paid a visit. One visit, for sure. More than one? Not so sure. But can’t you envision the bear with its extremities wrapped around this trunk as it climbs. I looked for other bear trees to no avail, but suspect they are there. Docents and trackers–we have a mission.

One visit, for sure. More than one? Not so sure. But can’t you envision the bear with its extremities wrapped around this trunk as it climbs. I looked for other bear trees to no avail, but suspect they are there. Docents and trackers–we have a mission. And what might the bear be seeking? Beech nuts. Viable trees. Life is good.

And what might the bear be seeking? Beech nuts. Viable trees. Life is good. Exactly where is the bear tree? Think left on red. When you get to this coppiced red maple tree, rather than turning right as is our driving custom, take a left and you should see it. Do remember that everything stands out better in the winter landscape.

Exactly where is the bear tree? Think left on red. When you get to this coppiced red maple tree, rather than turning right as is our driving custom, take a left and you should see it. Do remember that everything stands out better in the winter landscape. As delicate as anything in the china shop is the nest created by bald-faced hornets.

As delicate as anything in the china shop is the nest created by bald-faced hornets. Well, it appears delicate, but the nest has been interwoven with the branches and twigs–making it strong so weather doesn’t destroy it. At the bottom is, or rather was, the entrance hole.

Well, it appears delicate, but the nest has been interwoven with the branches and twigs–making it strong so weather doesn’t destroy it. At the bottom is, or rather was, the entrance hole. Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) grows abundantly beside younger beech trees. Though the flowers are now past their peak, I found a couple of dried ribbony petals extending from the cup-shaped bracts. China cups? No, but in the winter setting, the bracts are as beautiful as any flower.

Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) grows abundantly beside younger beech trees. Though the flowers are now past their peak, I found a couple of dried ribbony petals extending from the cup-shaped bracts. China cups? No, but in the winter setting, the bracts are as beautiful as any flower.

With the Balds in Evans Notch forming the backdrop, the brook is home to numerous beaver lodges, including these two.

With the Balds in Evans Notch forming the backdrop, the brook is home to numerous beaver lodges, including these two. Layers speak of generations and relationships.

Layers speak of generations and relationships. Close proximity mimics the mountain backdrop.

Close proximity mimics the mountain backdrop.

And sometimes, I just have to wonder–how does this tree continue to stand?

And sometimes, I just have to wonder–how does this tree continue to stand? Leatherleaf fields forever.

Leatherleaf fields forever. Spring is in the offing.

Spring is in the offing. Wintergreen offers its own sign of the season to come.

Wintergreen offers its own sign of the season to come. In the meantime, it’s still winter and this hemlock stump with a display of old hemlock varnish shelf (Ganoderma tsugae) caught my eye. By now, I was on the green trail.

In the meantime, it’s still winter and this hemlock stump with a display of old hemlock varnish shelf (Ganoderma tsugae) caught my eye. By now, I was on the green trail. But it’s what I saw in the hollow under the stump, where another tree presumably served as a nursery and has since rotted away, that made me think about how this year’s lack of snow has affected wild life. In the center is ruffed grouse scat. Typically, ruffed grouse burrow into snow on a cold winter night. Snow acts as an insulator and hides the bird from predators. I found numerous coyote and bobcat tracks today. It seems that a bird made use of the stump as a hiding spot–though not for long or there would have been much more scat.

But it’s what I saw in the hollow under the stump, where another tree presumably served as a nursery and has since rotted away, that made me think about how this year’s lack of snow has affected wild life. In the center is ruffed grouse scat. Typically, ruffed grouse burrow into snow on a cold winter night. Snow acts as an insulator and hides the bird from predators. I found numerous coyote and bobcat tracks today. It seems that a bird made use of the stump as a hiding spot–though not for long or there would have been much more scat.

Apparently it circled the area before flying off.

Apparently it circled the area before flying off.