A change of plans today meant I had time for a trek to Narramissic Farm and the historic bear trap in South Bridgton before the rain began.

From Ingalls Road, where I decided to park, I took in the view of the front fields and house.

Narramissic Road is passable, but I wanted to slow down and soak it all in.

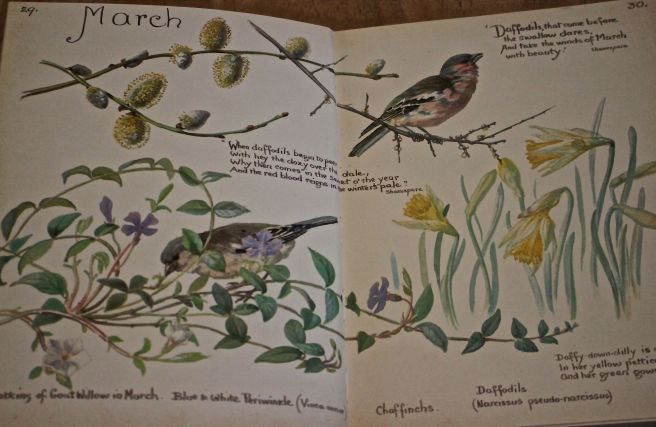

From pussy willows to

fuzzy staghorn sumac, I was thankful I’d taken time for the noticing.

The Bridgton Historical Society acquired the 20-acre property in 1987 when it was bequeathed by Mrs. Margaret Monroe.

Turning the clock back to 1797, William Peabody, one of Bridgton’s first settlers, built the main part of the house.

Peabody sold the farm to his daughter Mary and her husband, George Fitch, in 1830 and they did some updating while adding an ell.

The Fitches had a barn erected that has come to be known as the Temperance Barn; historical records claim it to be so named “because it was raised without the traditional barrel of rum.”

Both the barn and the house are in need of repair, but I couldn’t help but wonder about what mighty fine structures they were in their day. While today, a visit to the farm feels like you’re in the middle of nowhere, during its heyday it was located in the center of somewhere–at the junction of two roads that have since been abandoned.

When Mrs. Monroe purchased the property in 1938, she named it Narramissic, apparently an Abenaki word for “hard to find” because it reflected her long search for just the right piece of real estate.

A blacksmith shop is located between the house and Temperance Barn, and beside the trail I chose to follow through another field and off into the woods.

Massive stone walls indicate the fields had been plowed.

Even today, “stone potatoes” continue to “rise” from the ground, making them one of the farmer’s best crops.

My destination was two-fold: the quarry and bear trap. But along the trail, I stopped to smell the roses. Or at least admire the beauty of pearly everlasting in its winter form.

Several trees had snapped in the season’s wind, including a gray birch that scattered scales and seeds as it crashed to the ground.

But . . . because the top of the tree was no longer in the wind zone, a surprising number of catkins continued to dangle–all the better for me to see. Notice the shiny seeds attached to the scales.

The tree speaks of generations past and into the future.

Further along, I found a wavy and rubbery jelly ear (Auricularia auricla) beside a gray birch seed.

Finally, I reached my turn-off.

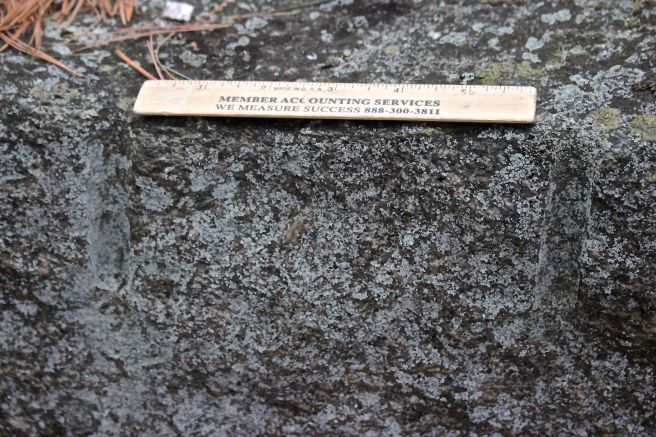

This is the spot from which the foundations for the buildings were quarried so long ago, using the plug and feather technique that was common in that time.

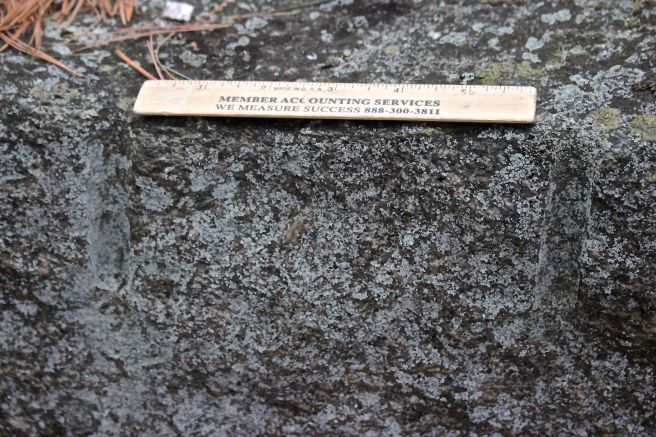

Life of a different sort has overtaken some of the stones–common toadskin lichen covers their faces.

In its dry form, it looks perhaps like the surface of a foreign planet, but this is another lichen that turns green when wet–allowing the “toad” to become visible.

Speaking of becoming visible, I noticed the bishop’s face topped with a mitre as water dripped off the rocks and froze. My thoughts turned to my sister–she doesn’t always see what I see, but maybe this one will work for her.

Heading back out to the main trail, I startled a snowshoe hare and of course, didn’t have my camera ready. As I turned toward the bear trap, I continued in the land of the beech trees. Most are too young to produce fruit, but I looked for larger trees and, of course, checked for claw marks.

The best I found were slashes–probably caused by another tree rubbing against this one.

Oh, and some initials carved by one very precise bear.

I was almost there when I encountered a “No Parking” sign. A new “No Parking” sign. On a trail in the middle of nowhere that used to be somewhere. The pileated woodpeckers obviously ignored it. Me too.

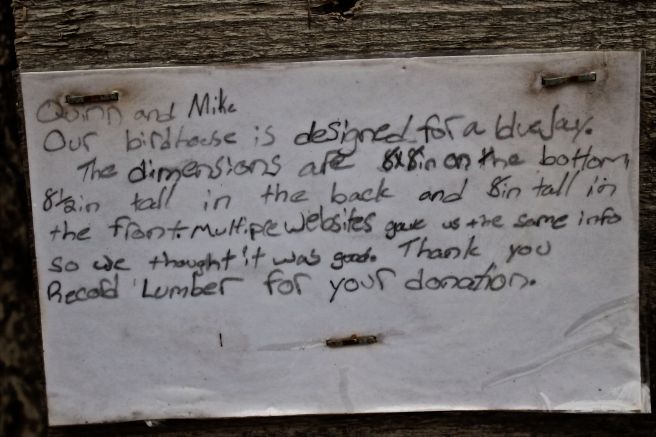

At last, Bear Trap! According to an August 17, 1963 article in the Bridgton News, “Enoch Perley, early settler of South Bridgton, built his first house in 1777 and brought his bride to their new home in 1778. [I believe this was at Five Fields Farm.]

As Enoch acquired livestock, he was much troubled by depredations from bears. He built a bear trap on the hill back of his first home . . .

Tradition says that four bears were caught in this trap–not enough! So Mr. Perley later had an iron bear trap made which took care of eight bears. Without a doubt, many were disposed of by him personally. A story is told that in an unarmed encounter with a bear and two cubs beside a wood road at dusk, Mr. Perley allegedly strangled the mother bear with his garters . . .”

The article continues, “The bear trap is built of stone. A large stone door is suspended and as the bear takes the bait, he trips the lever and is caught in the stone enclosure.”

I looked inside and found no one in residence. In a December 1954 issue of the Bridgton News, a brief article states: “The old stone bear trap on the mountain in South Bridgton known as ‘Fitch’s Hill,’ unused for more than one hundred years, has been reactivated by Dr. Fred G. Noble and Gerald Palmer and put in readiness to capture a bear.” As the story goes, they never did succeed.

A side view.

And a rear view. A few years ago there was talk of moving this monument because land ownership had changed. I hope it stays put because its authenticity would be lost in a move.

Just below the trap, I noticed a white hue decorating only one of a bunch of young pine trees. I can’t say I’ve ever seen this before or venture a guess about its origin. I’m waiting to hear back for our district forester–maybe he has some insight.

As I headed back down the trail and the barn came into view, I spied a single red pine thrown into the mix of forest species that have taken over this land.

Ever on my bear claw quest, I checked the bark of this tree. Though beech provides an easy display of such marks, it’s not the only species of choice. Among others, single red pines that appear to be anomalies have been known to receive a visit.

There was sudden movement as I approached the pine and then what to my wondering eyes should appear, but a second snowshoe hare! It paused long enough for me to snap a photo. Do you see it? Also known as the varying hare, its fur is still white.

Behind the tree, I found where it had been dining and defecating.

As I crossed the upper field, the ridge line of Pleasant Mountain and ski trails at Shawnee Peak made themselves known to the west. And beyond the farmhouse, the White Mountains.

And then,

and then . . . an oversized bud captured my attention as I walked back down the road.

Shagbark hickory isn’t a common species around here. But, Jon Evans of Loon Echo Land Trust had recently told me some mature trees were found on a property in South Bridgton that is under conservation easement. (We actually may visit them tomorrow). The bulbous, hairy bud scales and large leaf scar made even the young trees easy to identify. Curiously, according to Forest Trees of Maine, the wood “was formerly used in the manufacture of agricultural implements, axe and tool handles, carriages and wagons, especially the spokes and rims of the wheels.” That fits right in with the neighborhood I’d been visiting.

One final view–yup, it’s mud season in western Maine. But still worth a trek to bear trap and back. Thankfully, the rain held off until my drive home.