To say the insects of Lovell are the insects of Maine . . . are the insects of New England . . . is too broad a statement as we learned last night when Dr. Michael Stastny, Forest Insect Ecologist at the Atlantic Forestry Centre in Fredericton, Canada, spoke at a Greater Lovell Land Trust talk Mike helped us gain a better understanding of the relationship between trees, invasive insects and climate change in our grand State of Maine.

And then this morning, he led us down the trail on land conserved through the GLLT as a fee property and one held under conservation easement work.

From the get-go, our curiosity was raised and we began to note every little motion above, at eye level, and our feet.

Sometimes, what attracted our attention proved to be not an insect after all for it had two extra legs, but still we wondered. That being said, the stick we used to pick it up so we could take a closer look exhibited evidence of bark beetles who had left their signature in engraved meandering tunnels.

A bit further along, Mike pulled leaf layers apart to reveal the work of leafminers and our awe kicked up an extra notch. Leafminers feed within a leaf and produce large blotches or meandering tunnels. Though their work is conspicuous, most produce injuries that have little, if any, effect on plant health. Thankfully, for it seems to me that leaves such as beech are quite hairy when they first emerge and I’ve always assumed that was to keep insects at bay, but within days insect damage occurs. And beech and oak, in particular, really take a beating. But still, every year they produce new leaves . . . and insects wreak havoc.

Leafminers include larvae of moths (Lepidoptera), beetles (Coleoptera), sawflies (Hymenoptera) and flies (Diptera). I’m still trying to understand their life cycles, but today we got to see their scat when Mike pulled back a leaf layer! How cool is that? Instantly, I recognized a new parlor trick that I can’t wait to share with the GLLT after-school Trailblazers program we offer through Lovell Recreation.

As for today, Mike’s mother-in-law, Linda, tested the wow factor on her granddaughter and we knew we had a winner.

Our attention was then directed to the tussock moth caterpillars, including the hickory tussock moth that seems to enjoy a variety of leaf flavors.

And we found another tussock entering its pupating stage. We didn’t dare touch any of them for the hair of the tussocks can cause skin irritation and none of us wanted to deal with that.

Our next find was a leaf roller, and for me the wonder is all about the stitches it creates to glue its rolled home closed.

Eventually we reached a wildflower meadow where our nature distraction disorder shifted a bit from insects to flowers, including local goldenrods.

There was much to look at and contemplate and everyone took advantage of the opportunity to observe on his/her own and then consult with others.

One insect we all noted was the Silvery Checkerspot Butterfly. It’s a wee one and in the moment I couldn’t remember its name.

But . . . it remembered how to canoodle and we reveled in the opportunity to see such.

Our final insect notification was a bumblebee on the Joe-Pye-Weed. A year ago we had the opportunity to watch the bumblebees and honey bees in this very meadow, but today there were no honeybees because a local beekeeper’s hives collapsed last winter.

Our public walk ended but the day continued and I move along to the Kezar River Reserve to enjoy lunch before an afternoon devoted to trail work.

Below the bench that sits just above the river, I love to check in on the local exuvia–in this case a darner that probably continues to dart back and forth along the shoreline, ever in search of a delectable meal.

Landing frequently for me to notice was an Autumn Meadowhawk Dragonfly, its body all ruby colored and legs reddish rather than black.

My goal was to slip down to the river level like the local otters might and as I moved along I startled a small snake–a milk snake. Not an insect . . . but still!

Because I was there, so was the female Slaty Slimmer Dragonfly, and she honored me by pausing for reflection.

Apparently I wasn’t the only one to notice her subtle beauty, for love was in the air and on the wing.

Lovell hosts many, many insects, but I certainly have a few favorites that change with the season and the location. Today, Ruby Meadowhawks were a major part of the display.

Note the yellowish-brown face; yellowish body for a female; and black triangles on the abdomen, and black legs.

Our findings today were hardly inclusive, but our joy in noticing and learning far outweighed what the offerings gathered.

Ruby, Slaty, Miner, Tussock, Checkerspot, so many varieties, so many Insects of Lovell, and we only touched on the possibilities. Thank you, Mike, for opening our bug eyes!

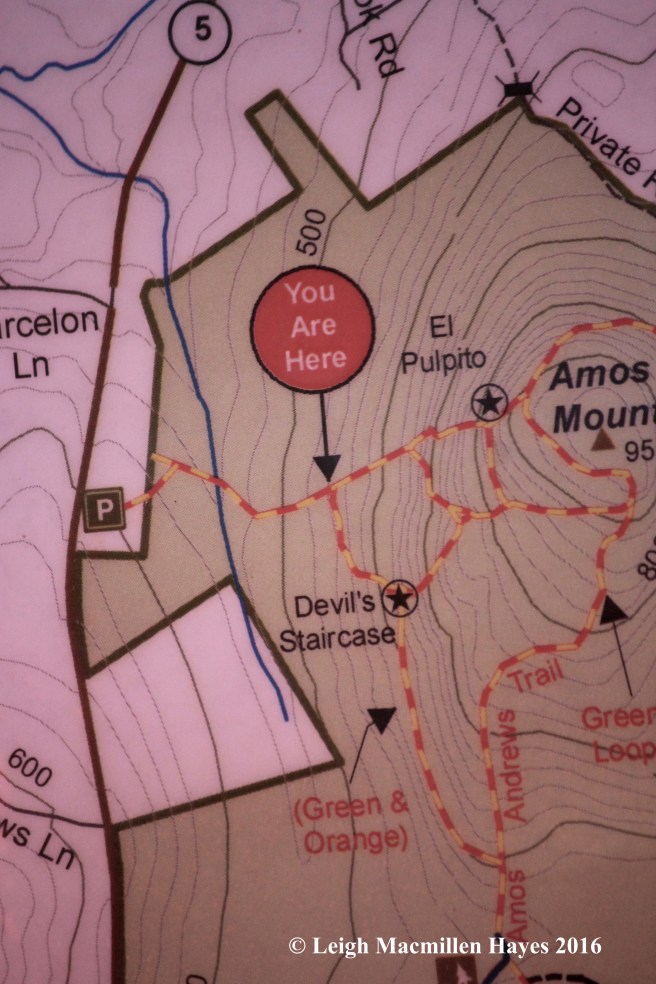

From the parking lot, I decided to begin via the blue trail by the kiosk. It doesn’t appear on the trail map, but feels much longer than the green trail–possibly my imagination. Immediately, I was greeted at the door of the shop by sweet fern, aka Comptonia peregrina (remember, it’s actually a shrub with foliage that appear fern-like). The striking color and artistic flow of the winter leaves, plus the hairy texture of the catkins meant I had to stop and touch and admire.

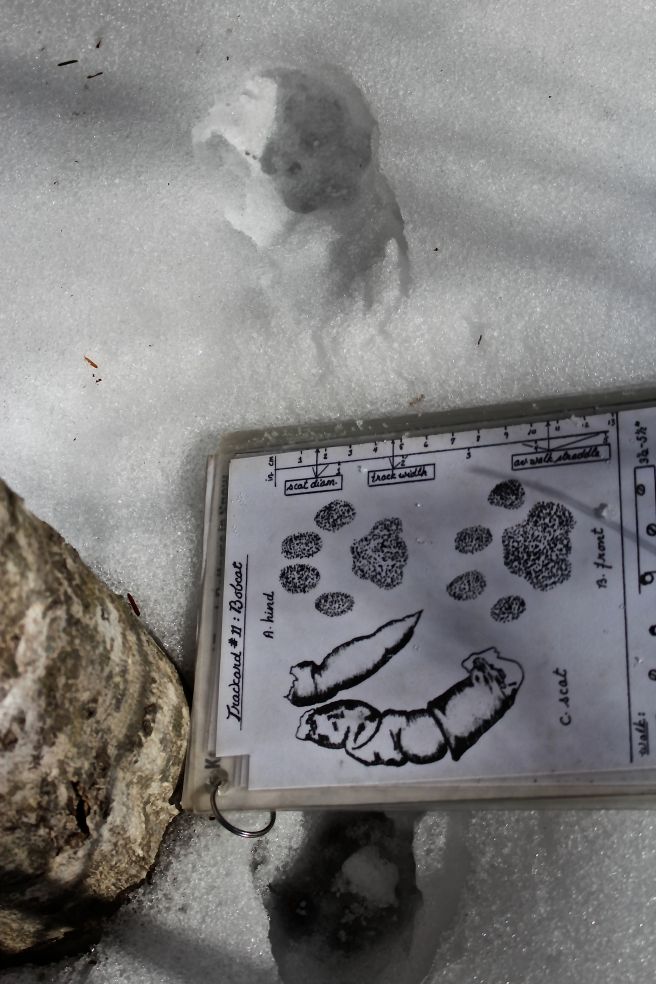

From the parking lot, I decided to begin via the blue trail by the kiosk. It doesn’t appear on the trail map, but feels much longer than the green trail–possibly my imagination. Immediately, I was greeted at the door of the shop by sweet fern, aka Comptonia peregrina (remember, it’s actually a shrub with foliage that appear fern-like). The striking color and artistic flow of the winter leaves, plus the hairy texture of the catkins meant I had to stop and touch and admire. And only steps along the trail another great find–bobcat tracks. This china shop immediately appealed to moi.

And only steps along the trail another great find–bobcat tracks. This china shop immediately appealed to moi. My

My  When I got to a ledgy spot, I decided to explore further–thinking perhaps Mr. Bob might have spent some time here. Not so–in the last two days anyway.

When I got to a ledgy spot, I decided to explore further–thinking perhaps Mr. Bob might have spent some time here. Not so–in the last two days anyway. The best find in this spot–red squirrel prints. A few things to notice–the smaller feet that appear at the bottom of the print are the front feet–often off-kilter. Squirrels are bounders and so as the front feet touch down and lift off the back feet follow and land before the front feet in a parallel presentation. In a way, the entire print looks like two exclamation points.

The best find in this spot–red squirrel prints. A few things to notice–the smaller feet that appear at the bottom of the print are the front feet–often off-kilter. Squirrels are bounders and so as the front feet touch down and lift off the back feet follow and land before the front feet in a parallel presentation. In a way, the entire print looks like two exclamation points. As I plodded along, my eyes were ever scanning and . . . I was treated to a surprise. Yes, a beech tree. Yes, it has been infected by the beech scale insect. And yes, a black bear has also paid a visit.

As I plodded along, my eyes were ever scanning and . . . I was treated to a surprise. Yes, a beech tree. Yes, it has been infected by the beech scale insect. And yes, a black bear has also paid a visit. One visit, for sure. More than one? Not so sure. But can’t you envision the bear with its extremities wrapped around this trunk as it climbs. I looked for other bear trees to no avail, but suspect they are there. Docents and trackers–we have a mission.

One visit, for sure. More than one? Not so sure. But can’t you envision the bear with its extremities wrapped around this trunk as it climbs. I looked for other bear trees to no avail, but suspect they are there. Docents and trackers–we have a mission. And what might the bear be seeking? Beech nuts. Viable trees. Life is good.

And what might the bear be seeking? Beech nuts. Viable trees. Life is good. Exactly where is the bear tree? Think left on red. When you get to this coppiced red maple tree, rather than turning right as is our driving custom, take a left and you should see it. Do remember that everything stands out better in the winter landscape.

Exactly where is the bear tree? Think left on red. When you get to this coppiced red maple tree, rather than turning right as is our driving custom, take a left and you should see it. Do remember that everything stands out better in the winter landscape. As delicate as anything in the china shop is the nest created by bald-faced hornets.

As delicate as anything in the china shop is the nest created by bald-faced hornets. Well, it appears delicate, but the nest has been interwoven with the branches and twigs–making it strong so weather doesn’t destroy it. At the bottom is, or rather was, the entrance hole.

Well, it appears delicate, but the nest has been interwoven with the branches and twigs–making it strong so weather doesn’t destroy it. At the bottom is, or rather was, the entrance hole. Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) grows abundantly beside younger beech trees. Though the flowers are now past their peak, I found a couple of dried ribbony petals extending from the cup-shaped bracts. China cups? No, but in the winter setting, the bracts are as beautiful as any flower.

Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) grows abundantly beside younger beech trees. Though the flowers are now past their peak, I found a couple of dried ribbony petals extending from the cup-shaped bracts. China cups? No, but in the winter setting, the bracts are as beautiful as any flower.

With the Balds in Evans Notch forming the backdrop, the brook is home to numerous beaver lodges, including these two.

With the Balds in Evans Notch forming the backdrop, the brook is home to numerous beaver lodges, including these two. Layers speak of generations and relationships.

Layers speak of generations and relationships. Close proximity mimics the mountain backdrop.

Close proximity mimics the mountain backdrop.

And sometimes, I just have to wonder–how does this tree continue to stand?

And sometimes, I just have to wonder–how does this tree continue to stand? Leatherleaf fields forever.

Leatherleaf fields forever. Spring is in the offing.

Spring is in the offing. Wintergreen offers its own sign of the season to come.

Wintergreen offers its own sign of the season to come. In the meantime, it’s still winter and this hemlock stump with a display of old hemlock varnish shelf (Ganoderma tsugae) caught my eye. By now, I was on the green trail.

In the meantime, it’s still winter and this hemlock stump with a display of old hemlock varnish shelf (Ganoderma tsugae) caught my eye. By now, I was on the green trail. But it’s what I saw in the hollow under the stump, where another tree presumably served as a nursery and has since rotted away, that made me think about how this year’s lack of snow has affected wild life. In the center is ruffed grouse scat. Typically, ruffed grouse burrow into snow on a cold winter night. Snow acts as an insulator and hides the bird from predators. I found numerous coyote and bobcat tracks today. It seems that a bird made use of the stump as a hiding spot–though not for long or there would have been much more scat.

But it’s what I saw in the hollow under the stump, where another tree presumably served as a nursery and has since rotted away, that made me think about how this year’s lack of snow has affected wild life. In the center is ruffed grouse scat. Typically, ruffed grouse burrow into snow on a cold winter night. Snow acts as an insulator and hides the bird from predators. I found numerous coyote and bobcat tracks today. It seems that a bird made use of the stump as a hiding spot–though not for long or there would have been much more scat.

Apparently it circled the area before flying off.

Apparently it circled the area before flying off.