When I sent out the invite to the Maine Master Naturalist Program’s Lewiston 2013 class for a tracking expedition at one of two possible locations, grad Alan responded, “Any place you pick in western Maine is fine; you know the area and conditions well. The only request I have is for you to try to show me a ‘bear tree.’”

Bingo! I pulled a third location out of my hat because it was within an hour of those who would join us and I knew that it passed the bear tree test.

And so six of us met at 10am, strapped on our snowshoes, and ventured forth. It’s always such a joy to be with these peeps and talk and laugh and share a brain.

Because our focus at first was on beech bark while we looked for bear claw marks left behind, we also shared an imagination. One particular tree made us think of a horseshoe.

Eventually we found a few trunks with the etched scratches of bear claws that had grown wider with the years. After the first find, which was actually on a different tree, the others developed their bear tree eyes and became masters at pointing them out.

And though we’d come to track, there wasn’t a whole lot of movement in the preserve except for the occasional deer. But . . . we still found plenty to fascinate us, including Violet-toothed Polypore.

Alan was the fungi guru of the group and so to him we turned to confirm our ID. We were correct, but in the process he taught us something new about this gregarious mushroom. There are two types of Violet-toothed: Trichaptum biforme grows on hardwoods; Trichaptum abietinum grows only on conifers. Now we just need to remember that. Before our eyes the former reached to the sky on the red maple.

All along, as I’ve done all winter, I searched for an owl in a tree. Penny found one for me. Do you see it?

What I actually saw more than the owl was the face of a bear. OK, so I warned you that we took our imaginations with us.

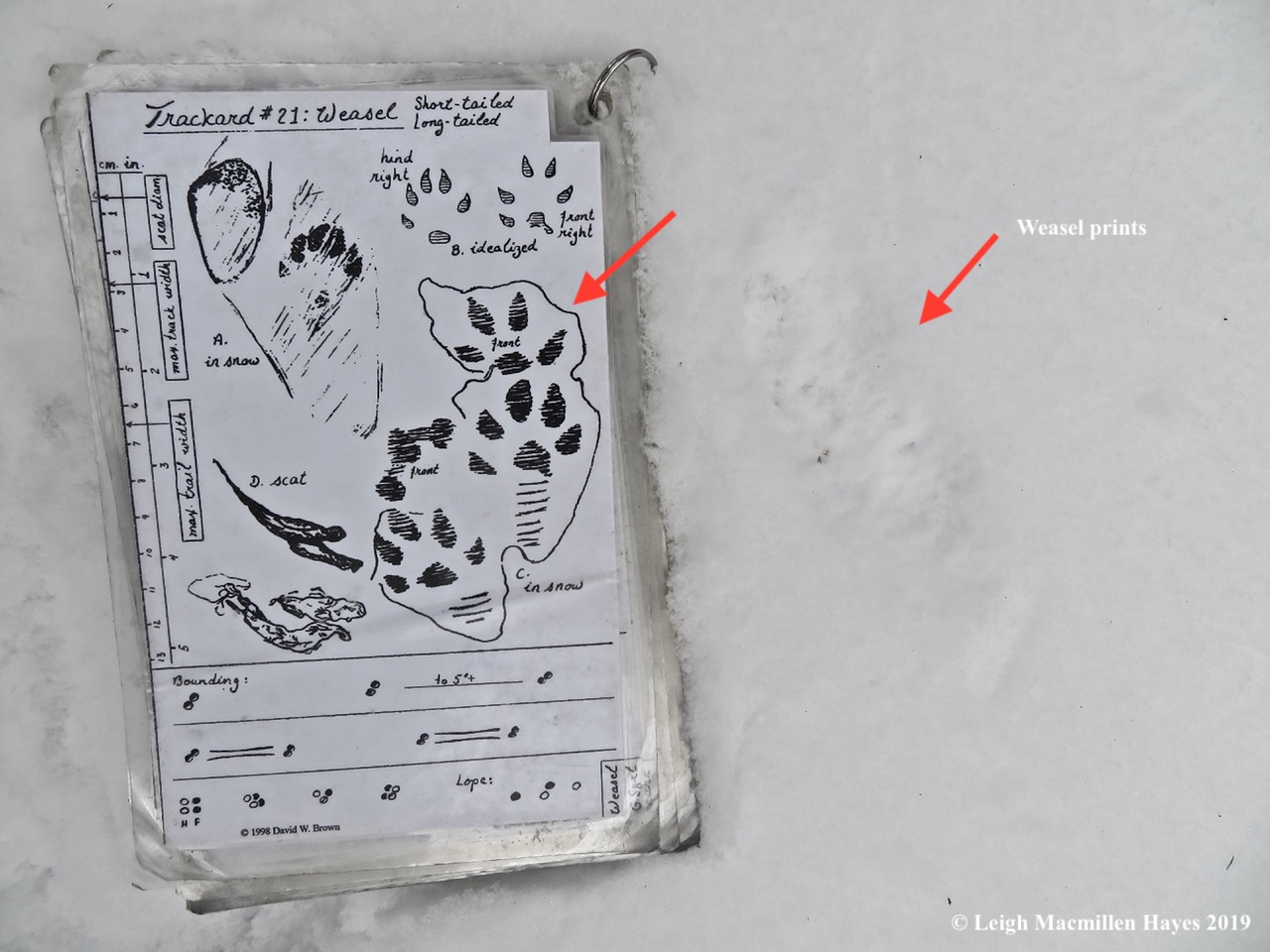

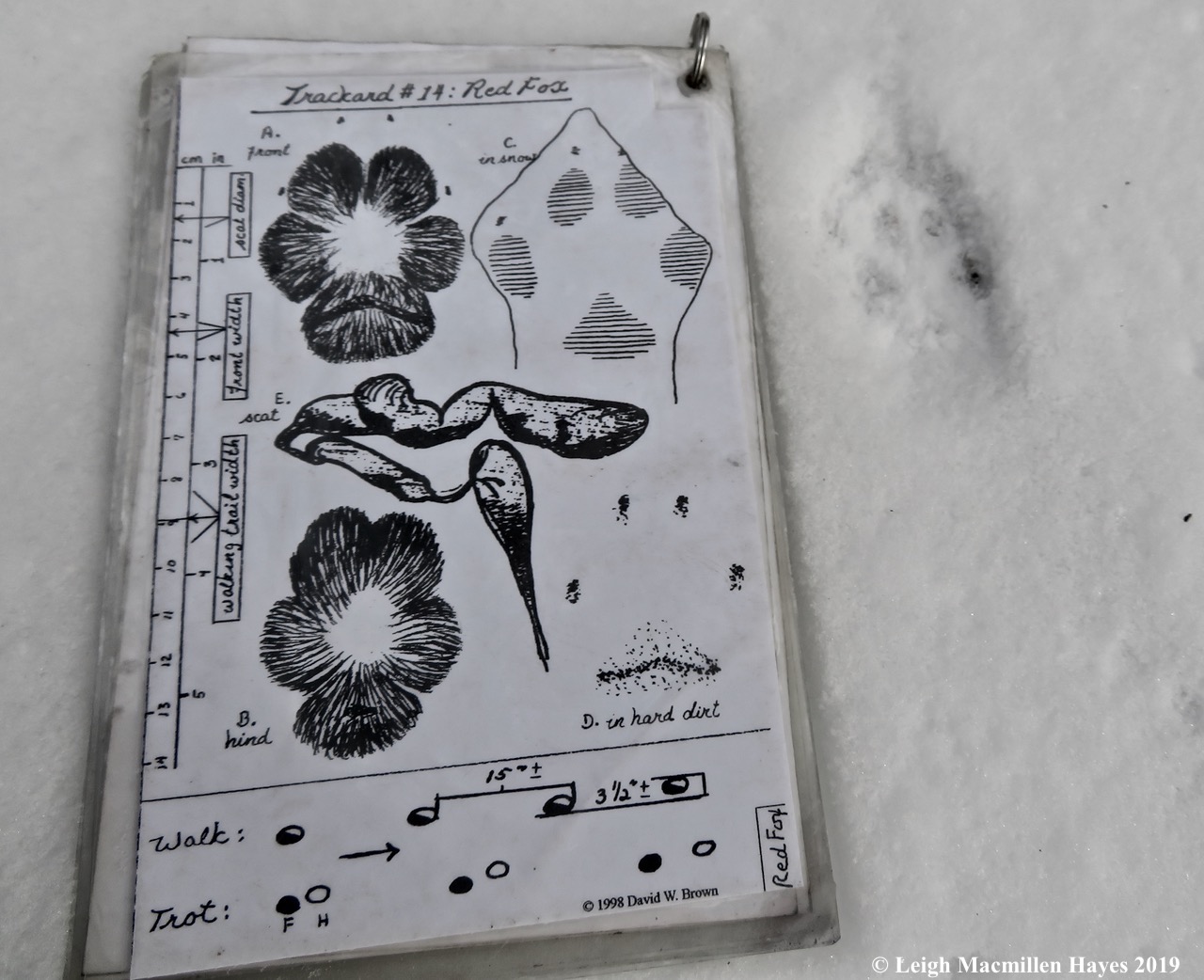

We were almost down to the water, when the group paused. Tracks at last. Near water. Track pattern on a diagonal meaning one foot landed in front of the other in a consistent manner for each set of prints. Trail width or straddle: almost three inches. Stride we didn’t measure because it varied so much, but it was obvious that this mammal bounded through the landscape. Identification: mink. Repeatedly after first finding the tracks, we noted that it had covered a lot of territory.

At last, we made our way out onto the wetland associated with South Pond and followed the tracks of a much bigger beast–in fact multiple beasts: snowmobiles.

Rather than find lunch rock, we chose lunch lodge and stood in the warm sun to enjoy the view.

We did wonder if it was active and determined that though there had been some action in the fall as evidenced by the rather fresh looking sticks, there was no vent at the top so we weren’t sure any beavers were within. Maybe it was their summer cottage.

Close by, however, we found another lodge and the vent was open so we didn’t walk too near.

Because we were on the wetland, we did pause to admire the cattails, their seeds exploding forth like a fireworks finale (but of the silent type, which I much prefer).

Back on the trail, the bark of another tree stopped us. We looked at the lenticels, those lines that serve as a way to exchange gases much like our skin pores, and noted that they were thin rather than the raised figure 8s of a pin cherry.

We had a good idea of its name, but to be sure we conducted a sniff test.

Smells like . . . wintergreen! We were excited to have come face to face with black or sweet birch. Some also call it cherry birch. Hmmm . . . why not wintergreen birch? Because, yellow birch, a relative, also has that wintergreen scent when you scratch the bark, especially of a twig.

Continuing along, the temperature had risen and snow softened so periodically we had to help each other scrape snowballs off the bottoms of shoes.

Otherwise the feeling was one of walking on high heels.

As I said earlier, all kinds of things stopped us, including the straight lines of the holes created by sapsuckers, those warm-weather members of the woodpecker family. One in the neighborhood apparently decided to drum to a different beat as noted by the musical notes of the top line.

Speaking of woodpeckers, for a few minutes we all watched a pileated and admired its brilliant red crest in the afternoon sun, but we couldn’t focus our cameras on it quickly enough as it flew from tree to tree. We did, however, pause beneath a tree where it had done some recent excavation work.

And left behind a scat that resembled a miniature birch tree.

At last, four hours and two miles after starting (we’d intended to only be out for three), we’d circled around and stopped again at the kiosk to look at the map. Do note that we’d also picked up a passenger along the way for Carl Costanzi, a Western Foothills Land Trust board member and steward of the Virgil Parris Forest came upon us and joined our journey. We picked his brain a bit about the property and he picked up a pair of snowshoes that had malfunctioned for one of us. Thank you, Carl! That’s going above and beyond your duties.

Before departing, we did what we often do–circled around and took a selfie.

And then we left with smiles in our hearts and minds for the time spent reconnecting. Our memories will always be filled with the discovery of the first bear tree not too long after we began. As Penny said, “That first one was a doozy.”

Our entire time together was a doozy–of a playdate.

Thanks Beth, Gaby, Roger, Alan, and Penny. To those of you who couldn’t join us, we talked about you! All kind words because we missed you.