It’s March, that most indecisive of months. And so, I decided to follow in the same pattern by choosing not one,

or two,

or even three,

but four–

all books about stone walls which are once again revealing their idiosyncrasies. These are the Books of March.

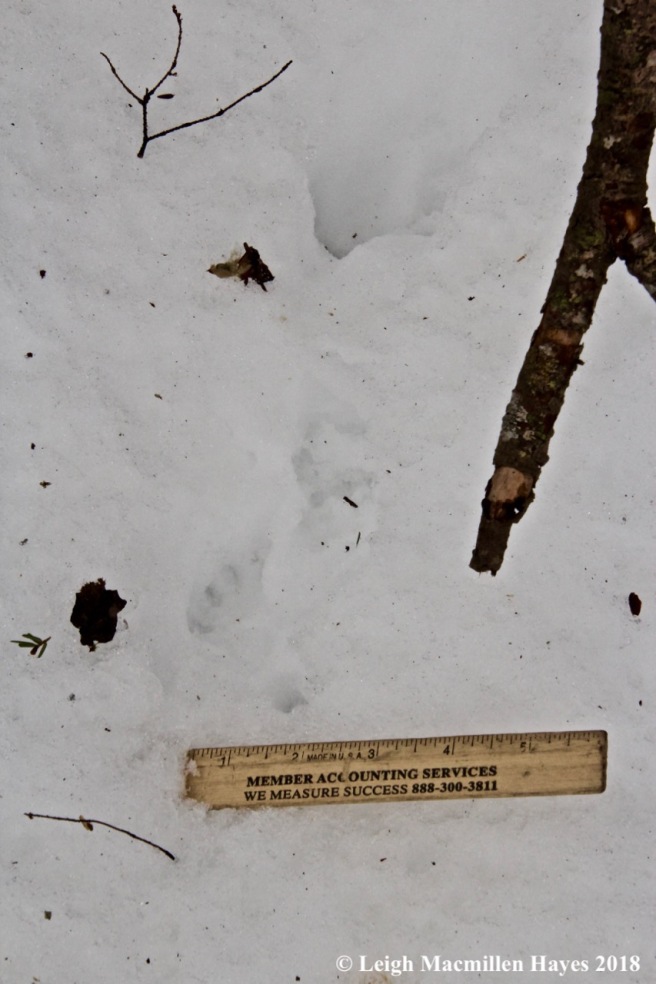

Walk along our woodland trail with me and you’ll know that something different happened there ages and ages ago. To reach the trail, we’ll need to pass through two stone walls. Continuing on, we’ll come to a cow path where several pasture pines, massive trees that once stood alone in the sun and spread out rather than growing straight up, must have provided shade for the animals.

They are the grandparents of all the pines that now fill this part of the forest.

Further out, one single wall widens into a double wall, indicating a different use of the land.

The walls stand stalwart, though some sections are more ragged than others. Fallen trees, roots, frost, weather, critters and probably humans have added to their demise, yet they are still beautiful, with mosses and lichens offering striking contrasts to the granite. Specks of shiny mica, feldspar and quartz add to the display. And in winter, snowy outlines soften their appearance.

The fact that they are still here is a sign of their endurance . . . and their perseverance. And the perseverance of those who built them. and yet . . . . the stone walls aren’t what they once were, but that doesn’t matter to those of us who admire them.

For me, these icons of the past conjure up images of colonial settlers trying to carve out a slice of land, build a house and maybe a barn, clean an acre or two for the garden and livestock and build walls. The reality is that in the early 1700s, when western Maine was being settled, stones were not a major issue. The land was forested and they used the plentiful timber to build. It wasn’t until a generation or two later, when so much timber had been harvested to create fields for tillage and pasture, that the landscape changed drastically, exposing the ground to the freezing forces of nature. Plowing also helped bring stones to the surface. The later generation of farmers soon had their number one crop to deal with–stone potatoes as they called them. These needed to be removed or they’d bend and break the blade of the oxen-drawn plowing rake.

Stone removal became a family affair for many. Like a spelling or quilting bee, sometimes stone bees were held to remove the stones from the ground. Working radially, piles were made as an area was cleared. Stone boats pulled by oxen transported the piles of stones to their final resting place where they were woven into a wall.

Eventually single walls, also called farmer or pasture walls, were built as boundaries, but mainly to keep animals from destroying crops. The advent of stone walls and fences occurred within a few years of homesteads being settled, but during the sheep frenzy of the early 1800s many more were built. Those walls were supposed to be 4.5 feet high and fence viewers were appointed by each town to make sure that farmers tended their walls.

Double walls were lower and usually indicated an area that was to be tilled. A typical double wall was about 4-10 feet wide and consisted of at least two single walls with smaller rubble thrown between.

Drive our back roads and you’ll see many primitive walls created when stone was moved from the roadway and tossed into a pile, or wander through the woods and discover stone walls and fountains in unexpected places. The sheep craze ended about 1840 after the sheep had depleted the pastures and younger farmers heeded the call to “Go west young man, go west.” The Erie Canal, mill jobs, and better farming beyond New England all added to the abandonment of local farms.

Today we’re left with these monuments of the past that represent years of hard labor. Building a wall was a chore. Those who rebuild walls now find it to be a craft.

Sam Black, who lives in Bridgton, Maine and spent twelve years rebuilding the walls on his property, once told me, “It was meditation time, like working in the garden. It’s one of those things you do philosophically and it lets you operate at a deeper level. You have time to think and contemplate as you work on the jigsaw puzzle.”

Frank Eastman of Chatham, New Hampshire, is the caretaker for the Stone House property in Evans Notch, and said when I asked if he’d ever worked on single walls, “No, I ain’t that good at balancing things. You got to have a pretty good ability to make things balance and a lot of the times your rock will titter until you put a small rock in just to hold it. No, I don’t want to monkey around with a single wall.”

Karl Gifford of Baldwin, Maine, told me, “I’m either looking for the perfect stone or trying to create the perfect space for the stone I’m working with. It takes a lot of practice, seeing what I need and being able to pick it out of the pile.” The entire time we chatted, his hands moved imaginary stones.

The more walls I encounter in the woods, the more respect I have for those who moved the stones and those who built the fences that became the foundation of life. Walk in the woods and you’ll inevitably find evidence that someone has been there before you–maybe not in a great many years, but certainly they’ve been there. Their story is set in stone.

If you care to learn more about stone walls, I highly encourage you to locate these books. I found all of them at my local independent book store: Bridgton Books.

Books of March:

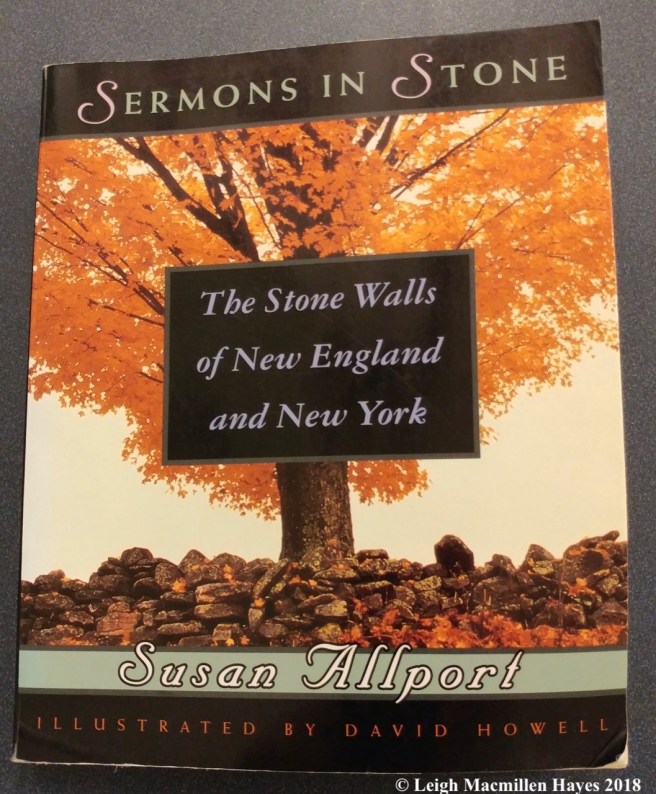

Sermons in Stone by Susan Alport, published 1990, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

A history of stone walls in New England.

Stone by Stone by Robert M. Thorson, 2002, Walker & Company.

A geological look at stone walls

Exploring Stone Walls by Robert M. Thorson, 2005, Walker & Company.

A field guide to determining a walls history, age, and purpose.

The Granite Kiss by Kevin Gardner, 2001, The Countryman Press.

A look at repairing walls of stone.

And now I leave you with this poem:

The Old Stone Fence of Maine

Shall I pay a tribute here at home,

To the Old Stone Fence of Maine?

It was here when you were born,

And here it will remain.

Stone monuments, to grand old sires,

Who, with a good right arm,

Solved problems little known to you,

E’re their “clearing,” was your farm.

When you see an Old Stone Fence,

Weed grown and black with age,

Let your mind’s eye travel backward

And read its written page.

And, as Moses left us words in stone,

That live with us today,

Almost, with reverence, let us read

What these Stone Fences say.

They tell of those who “blazed the trail,”

We are walking in today;

Those who truly “bore the burdens

In the heat of the day.”

For every stone was laid by hand,

First taken from the soil

Where giant trees were cut and felled,

Bare handed–honest toil.

The Stone Fence marked the boundary line

Whereby a home was known;

Gave them dignity, as masters

Of that spot they called their own.

The Stone Fence, guarded church and school

And the spots more sacred far,

The silent spots, in memory kept

For those who’ve “crossed the bar.”

Then, treasure this inheritance,

Handed down from sire to son,

Not for its worth, to you, today,

But for when, and why, begun.

For with it comes a heritage

Of manly brawn and brain,

That is yours today, from the builders

Of the Old Stone Fence of Maine.

~Isabel McArthur, 1920

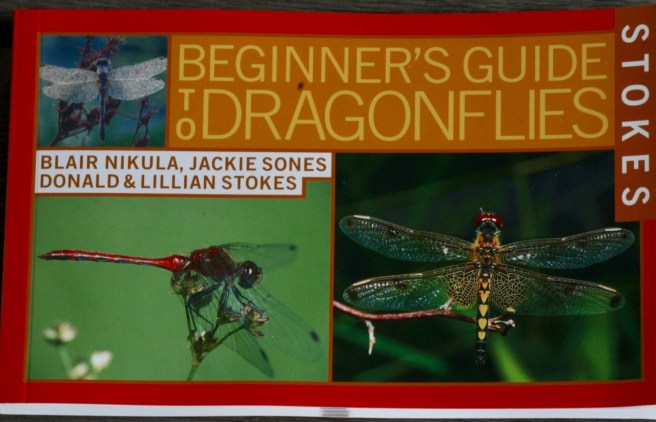

Thanks so much for the detailed and positive review of my book, A Beginner’s Guide to Recognizing Trees. It sounds like it would be great to take a hike with you. I really appreciate the good press. –mm

Liked by you